Re-envisioning the Future of Mountain School: Embracing Student-Centered Education

Mountain School is the Institute’s 30-year-old flagship program. Students (predominantly 5th graders) travel deep into the North Cascades to spend three days in its ecosystem establishing a foundational relationship with the natural world—one we hope they will carry with them for the rest of their lives. The Mountain School curriculum has undergone multiple small adjustments since its inception 30 years ago. Since then, there have been significant changes to state learning standards, the world we live in, and how we bridge the two to help prepare young people for the dynamic world and global issues we face.

In order to honor our past as well as meet students in their world today, we began looking at the ways our teaching and the Environmental Learning Center’s location within the North Cascades might not feel welcoming to all students. Contracting with Three Circles Center for Multicultural Environmental Education, we have created a new curriculum framework that is more student-centered and focuses on Next Generation Science Standards, climate literacy, and indigenous presence in this place.

Student-Centered Approach

We believe that all education is inherently cultural. How students learn to make meaning of their world via their experiences in both formal (classroom) and informal education settings like Mountain School is not “neutral.” This means that the millions of decisions educators make—ranging from where to set the learning venue, to what language to teach in, what content to teach, and how to teach and interact with each student—subliminally send messages to students about what is “normative” or “legitimate” knowledge and what is more in the realm of “superstition” or “non-academic.”

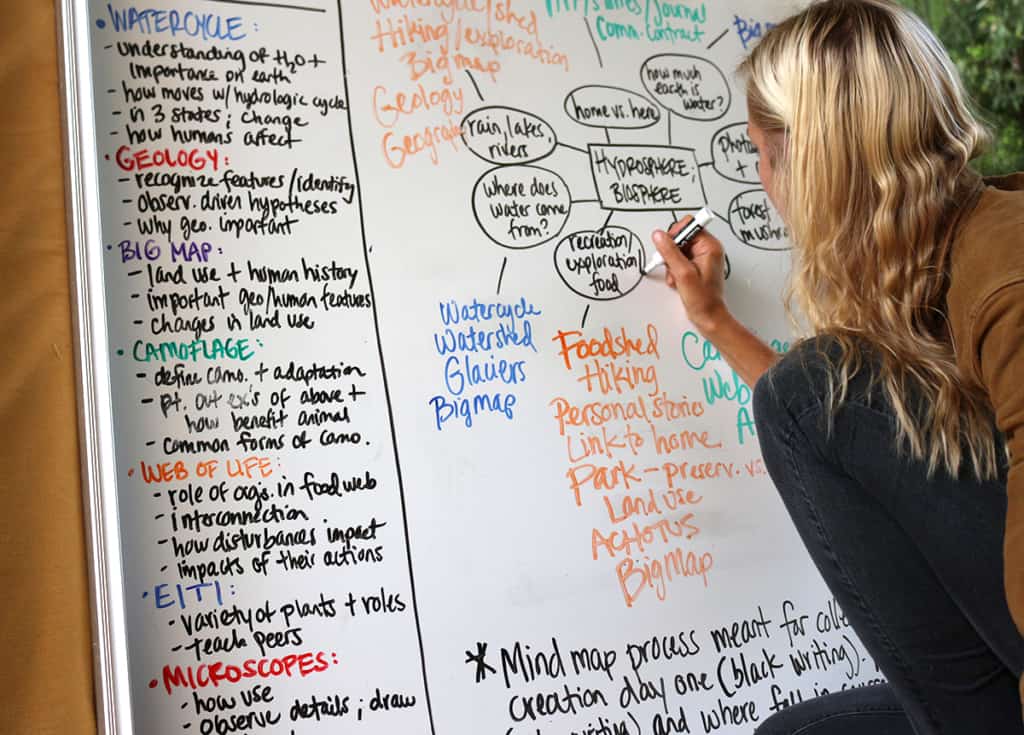

Teaching through a “student-centered” approach means purposefully curtailing the assumption that the educator is the sole source of knowledge. Rather, it sees students as arriving in educational spaces with their own, lived experience. Their knowledge is welcomed, acknowledged, and supported as the foundation for all supplementary learning that follows. To support this approach, the 2020 Mountain School redesign plans lessons as derivative of a central question or theme, and then students discuss what they already know about the subject and what they hope to learn. In this way, lessons become less directed by teachers in a “top-down” approach, and are instead directed via student-led inquiry and interest.

A student-centered approach also acknowledges that each student brings with them differing experiences, perspectives, and values that impact their experience and comfort at Mountain School. For most white people, the outdoors has always offered a place of solace and restorative healing, but for people of color, rural places and wildernesses are often associated with ancestral violence and trauma. At Mountain School, 39% of students identify as people of color and many of these students are the first in their family to ever visit a National Park. The new Mountain School curriculum will elevate the importance of culturally responsive teaching by helping students learn positive cultural identification. Under the new curriculum, our instructors will be trained to actively bring out the internal knowledge and experience of the child rather than telling them the “right, correct” way to view and know this place and the natural world.

Next Generation Science Standards

The new Mountain School curriculum more clearly aligns with Next Generation Science Standards (which were adopted as Washington State Science and Learning Standards in 2013). Drawing from these standards, the curriculum is based on a series of eight essential questions, that range from “What makes a place diverse?” to “How do humans depend on the Earth?”

Instruction will focus on creating the conditions for students to come to these questions on their own as a product of curated exploration and observation. As educators, it is our job to unearth and help our students examine their preconceptions of what a scientist is and does. When asked to imagine who a scientist is, many young people think of a person indoors, wearing a lab coat, looking at something through a microscope or in a beaker. They rarely, if ever, consider themselves.

Climate Literacy

Young people hold tremendous energy—of authentic voice, systemic change, and creative agency. Yet, in too many areas of their lives, young people face limited space to channel their energy, agency, and creative ideas for change. The new Mountain School curriculum introduces students to ways that climate change is impacting the North Cascades and the people of this region, and positions students to think about changes they may already be aware of and experiencing in their home communities and what we should do about it—how we should adapt and mitigate in response to these changes. Today’s job market prioritizes 21st century skills—creativity, risk taking, and ingenuity—above prudence and loyalty to “tried and true” ways of doing business. Now, in the midst of a global pandemic and a national reckoning on racism, these skills are even more valued. Indeed, they will prove to be essential to how we recover and rebuild in the coming decade. Giving Mountain School students increased opportunity to develop this creative muscle is crucial to their becoming the leaders that they already are.

Indigenous Presence and Stewardship of Place

In 2015, Washington State passed SB-5433 requiring all public schools teach tribal sovereignty curriculum, known as “Since Time Immemorial.” This curriculum, endorsed by all 29 of Washington state’s federally recognized tribes, focuses specifically on what it means for tribes to self-govern and ensures that students are able to locate and name tribal nations in their region. We intend to better support our school district partners in meeting this state mandate by incorporating Since Time Immemorial curriculum into the new Mountain School curriculum.

The Mountain School curriculum redesign aims to broaden student exposure to indigenous narratives and emphasize the interconnectedness of culture, identity, and the environment. For the past three generations, the public has been mass educated to believe that indigenous peoples’ cultural ways of life are only historic, and not ongoing in present times, and that their knowledge systems were unsophisticated, at best, and barbaric, at worst. For example, most Mountain School students are familiar with the Canadian border to our north and can conceptualize its ‘separation’ from the United States. However, it is far less common for students to apply similar understanding to the 29 sovereign indigenous nations within Washington State.

Land acknowledgements and discussions of sovereignty can encourage celebration of historical and ongoing stewardship within the North Cascades ecosystem, while more openly confronting the systemic oppression, dismissal, and decimation of indigenous culture in this space. Student-centered education spotlights native perspectives and the perspectives of other non-dominant identity groups whose cultural stories and values have historically been erased, disparaged, or otherwise deemed “non-academic.”

When it comes to Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics (STEM) education, there is a similar legacy of maintaining a hard distinction between what is and is not “scientific.” For example, it has only recently come to be scientifically legitimate to talk about plants’ ability to communicate with each other, but the idea that plants have agency and personhood is a very old indigenous belief. The new curriculum promotes a greater understanding of the continual presence of indigenous people in the North Cascades and reinforces the idea that non-dominant ways of knowing hold equal legitimacy.

Place teaches. Standing at the foot of a waterfall surrounded by Western Red Cedar and salal and sword fern ignites a different series of questions in students’ minds than what they can learn by reading about a waterfall or an alpine forest in a textbook or by watching a nature documentary on YouTube. We had planned to pilot this curriculum redesign with a handful of schools in Fall 2020, but due to COVID-19, we are waiting until it is safe for school groups to return to residential programming at the Learning Center. So much of this new curriculum depends on the three-day immersive duration of the program and the distinct geology, plants, and animals native to the north shore of Diablo Lake.

Teachers have told us that Mountain School radically shifts the academic identities some students have taken on at school. One teacher reflected, “Mountain School made students feel like they were academic kingpins while they were here and that’s not their identity at school.” We see this opportunity for students to surprise their peers (and themselves!) by excelling in areas they have previously been told they are “not good at” as the single most important outcome of this program. One teacher told us, “This group was one of our biggest groups with social-emotional needs. You sat down with us to address those needs, and your instructors changed tactics to get them what they need at every turn. Our students all went away feeling really proud of themselves. You have some really good people on staff who encourage students to push themselves as far as they want to go. There’s no judgment, no fear.” This student-centered approach, which allows us to cater to the individual needs of students, is central to what the new Mountain School curriculum is all about.

We are excited to pilot a curriculum explicitly designed to be student-directed and to affirm non-dominant cultural experiences in a post-pandemic era of Mountain School, and we are confident that these traits will lend themselves to being adaptable in the years ahead.

Written in collaboration with Zoe Wadkins, Codi Hamblin and Cara Stoddard.

I was one of the original teachers to go to mountain school when it was a tent experience in Newhalem. We ate under a blue tarp and I was honored be the one to get coffee ready for the staff in the early hours of the morning. The program has grown to a fantastic lodge experience.

The thing that has not changed is the impact on kids lives. As a middle school science teacher I could make connections to the students experience at Mountain School. It was a collective experience for Mount Vernon Fifth graders.

To this day students remember the experience with the “remember when”, stories of their time at Mountain School.

The chance to live and see nature as it is, is powerful for all students. This opportunity is vital as we navigate through a century where environmental issues will be at the forefront of our existence.