Terry Tempest Williams' intriguing meanderings

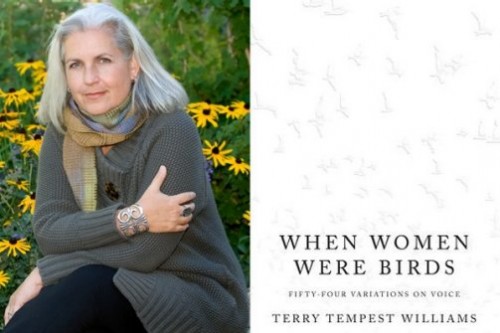

When Women Were Birds: Fifty-Four Variations on Voice reviewed

Note: Williams will be reading in Bellingham on June 21 as part of our “Nature of Writing” series with Village Books. More info at www.ncascades.org/events.

In recent years, Terry Tempest Williams has written about patriotism and democracy in America, Italian mosaics, the Sundance Film Festival, Rwandan genocide and Hieronymus Bosch’s fifteenth-century Flemish masterpiece, The Garden of Delights. Not bad for a so-called “nature writer.”

In her latest book When Women Were Birds: Fifty-Four Variations on Voice, the author returns to some of the themes found in Refuge: An Unnatural History of Family and Place, her highly-regarded 1991 environmental memoir that intertwines reflections on family, mortality and the Bear River Migratory Bird Refuge near her home in Salt Lake City.

The opening pages depict Williams’ mother, dying of ovarian cancer, passing on to her writerly daughter her lifetime collection of personal journals. The mother makes Williams promise not to read them until after she is gone. When that time comes to pass, Williams finds a plethora of colorful, clothbound journals:

The spines of each were perfectly aligned against the lip of the shelves. I opened the first journal. It was empty. I opened the second journal. It was empty. I opened the third. It, too, was empty, as was the fourth, the fifth, the sixth – shelf after shelf after shelf, all my mother’s journals were blank.

When Women Were Birds then is an investigation in to the mystery of all those white, untrammeled pages. As the story unfurls from this startling prelude, Williams explores the power of silence, Mormon culture, marriage, feminism, a supernatural history of birds, relationships between mothers and daughters and grandmothers and granddaughters and the central question, “What does it mean to have a voice?”

The narrative toggles between short, distinct stories from Williams’ life – how her Mormon ancestors came to settle in Utah, learning bird songs as a young girl with her grandmother, meeting her husband Brooke, studying natural history in the Grand Tetons – and more emotive meditations that aren’t bound by conventional logic.

Anyone who has read Williams mesmerizing literature before knows to expect a wide-ranging, unconventional and empathic journey. This one touches upon experimental composer John Cage, the extinct Chinese language Nushu, writer Wallace Stegner, Navajo mythology, a battle for wilderness legislation in the US Congress, Richard Strauss’ operas and her beloved Southern Utah red rock wilderness. In a holistic feat similar to Annie Dillard’s For the Time Being, the author successfully makes comprehensive and connected what the reader may have previously imagined disparate. This is the kind of book that changes the ways in which we see the world.

Still, beneath Williams’ intriguing meanderings, the presence of the blank journals haunt the reader.

My mother’s journals are a love story. Love and power. What she gave and what she withheld were hers to choose. Love is power. Power is not love. Both can be brutal. Both dance with control. Both can be intoxicating, leaving us out of control. But in the end it is love, not power, that endures and shows us the consequences of our choices. My mother chose me as the recipient of her pages, empty pages. She left me her “Cartographies of Silence.” I will never know her story. I will never know what she was trying to tell me by telling me nothing.

But I can imagine.

It is an enjoyable feat to behold the nimble mind of Williams dancing across time and terrain, flitting from topic to topic like a bird from branch to branch, her graceful and poetic prose the airborne track of her compassionate inquiry.