Reflections from the back of my horse

I am on my horse at the Pilchuck Tree Farm in Arlington with my mom. The air is cool and moist; the sun reflects off the glinting dew drops on the foliage repossessing the battered stumps and scars on the landscape. We travel on this trail silently, allowing our horses to navigate this place we have all visited so many times before.

The Tree Farm, once actively logged, is now home to a local recreation association, mostly horsemen and women, who come to this place to seek solitude from motorized vehicles and hunters amongst the recovering forests. My horse’s ears flick forward suddenly as he registers some sound known only to him, but a dismissive swivel back towards me indicates that whatever he heard has not been perceived as a threat.

The world is a different place from the back of a horse.

View from the back of Sheena

View from the back of Sheena

Experiencing the forest from horseback is unique. Each experience is shared between horse and rider, and both must take the other into account when reacting to their surroundings or an unexpected event. As animals of prey, horses have excellent hearing. Many times, my horse has known about the presence of a deer long before it bursts forth from a bush nearby. I have learned to gauge my surroundings by observing cues and reading my horse’s body language—they will often alert you to the presence of other animals long before you would decipher them on your own.

Along with their strong audible range, horses have a highly developed fight or flight response. After millions of years of co-evolution with large predatory animals, the threat perception of a horse remains incredibly strong. Pair that with a dichromatic (two-color, similar to red-green color blindness in humans) sense of sight and a simple puddle on the trail may actually be a monster specifically adapted to eating horse flesh. Often, coaxing and cajoling may be necessary to cross unfamiliar obstacles along the trail.

We continue along the trail, rising slightly from a recuperating clear cut into a shaded grove of Douglas fir trees. The air becomes denser, cooler. The birdsong shifts from thrush and warbler to sparrow and robin. Birds typically don’t mind horses, though my horse has been known to mind birds. Far off in the distance, a woodpecker drums against a snag. The wind grazes through my hair, and I pick up the sweet post-rain smell of steamy green forests, mixed with the sweet scent of my horse – a musky, dusty smell that only another horse-lover would understand.

(above two photos) The author working with Sheena, her first horse, who is now a dignified old lady

(above two photos) The author working with Sheena, her first horse, who is now a dignified old lady

The author training Thunder

The author training Thunder

I was five when I first remember climbing astride a horse. My mother, an avid horsewoman since childhood, desperately wanted a little girl to share her love of horses with. I was her first-born and subsequently, the majority of my childhood memories are from the back of a horse. It is on horseback that I feel most connected with the natural world. Horses have an uncanny ability to transcend the bridge between wild and domestic. Often, other animals are more accepting of my presence when I am on a horse, as though they recognize a kindred creature. Deer and other ungulates that would typically shy away from me on foot will frequently approach us while we are on horseback, inquisitively studying the horses.

There is a quote from the Quran about the creation of the horse that I heard some time ago but find myself habitually returning to:

When God created the horse, he said to the magnificent creature, ‘I have made thee as no other. All the treasures of the earth lie between thy eyes. Thy shall carry my friends upon thy back. Thy saddle shall be the seat of prayers to me. And thou shalt fly without wings, and conquer without sword; oh horse.’

One may never experience flight the way you can on the back of a galloping horse: Each hoof beat strikes the ground, resonating against the earth, the wind rushes past my ears, all I can hear is each footfall and the resounding, purring breath of my horse. The air stings my eyes and they tear up. I can barely keep focus on the ground ahead. Tears streaming down my face, we press onward, faster and faster up a hill. The trees alongside the trail blur into a green corridor as we rush by. We fly, covering distance, time, and space, all without wings. I am one with my horse and each thought I have he already knows. We effortlessly navigate the maze of trails, he of muscled velvet and I of leather and jeans. We near the meadow, our customary lunch spot, and slow down to a walk, both breathing hard and vivaciously fulfilled by the run.

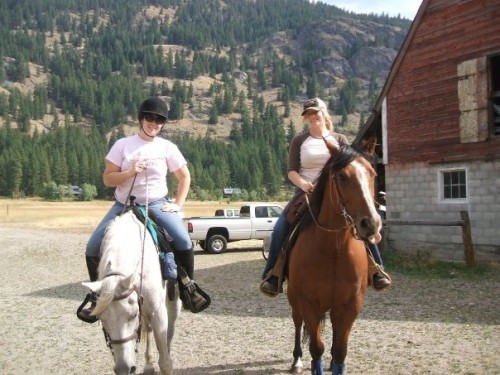

The author and a friend in Mazama

The author and a friend in Mazama

Thunder, blowing snow off the railing into Sahara’s face for snowy kisses

Thunder, blowing snow off the railing into Sahara’s face for snowy kisses

The meadow is open and inviting. It is the official halfway point in this trail system. Outfitted with a hitching post and a porta-potty, my horse knows that he is allowed a break whenever we reach this part of the ride. My mom and I climb off, tie up the horses, and enjoy our lunches. Overhead we can hear birdsongs and watch the clouds lazily roll through the valley. The Tree Farm is adjacent to the Stillaguamish River, still flush and murky with winter runoff. Even though we are within an area heavily impacted by humans and still in cell phone service, I consider this place wild.

Though not as pristine as my current lodging at the North Cascades Environmental Learning Center in North Cascades National Park, the Tree Farm is our local reprieve from the hustle and bustle of everyday life. Bears, coyotes, cougars, deer, squirrels, birds, chipmunks, and all kinds of native plants call the Pilchuck Tree Farm home. There is a quality of wildness here, and I feel most connected with that wildness when I am on the back of my horse. It’s as if my horse’s hooves root us to that space and the wildness. It is a feeling I seldom experience in my own hiking boots, whose man-made leather and rubber soles restrict that sense of rootedness. Perhaps it is because I am on an animal that I feel this way—an animal that represents freedom, beauty, and wildness.

We finish eating lunch, feed our leftover apple cores to the horses, and mount up again. As we descend back into the dark forest, I shoot the meadow a fleeting glance. It will be some time before we return to this place, an illness in the family will take precedence instead. And even though I don’t yet know this, I realize that each time we come here to ride is sacred. Our altar, though covered with logging wounds and power lines, represents life anew and recovered. Our prayers flow easily from the seat of our saddles, and our wings, though you can’t see them, will help carry us through these wild spaces.

Sahara Suval is a graduate student in Western Washington University and North Cascades Institute’s M.Ed program. During her graduate residency she is working as the Youth Programming Assistant and Grants Research Assistant. She grew up in Stanwood, WA and has been riding horses since age 5.

Beautiful, Sahara, a respite from the workday and an insight into a world that is unfamiliar to me.

Nicely done. You captured something essential, Sahara, and it makes me long to get out in the woods. Thanks for taking us with you on Thunder.

Ah Sahara, you capture the rapture so well!