John McMillan's Cabin: Traveling the paths of ghosts

By Hannah Newell, a M.Ed. Graduate student of the Institute’s 15th Cohort

Where would one place their grave in these woods? And how could one bury themselves? These two questions came to me as I was half delirious with exhaustion, wandering around on the west bank of Big Beaver Creek along Ross Lake. My cohort member and work study compliment, Joe Loviska, and I were on a two day excursion into the Ross Lake Recreation Area to document wildlife and for him, phenological stages as our season turns to spring. I was on a personal quest as well. The previous months leading up to this trip, I had been in contact with a number of resources to lend a hand in my discovery of the history of trapping in this area of the North Cascades.

The trappers and homesteaders were few and far between in this vast landscape of pinnacle mountains and dense forests. One could get lost among the giant cedars and accidentally wander into a forest of Devil’s Club without notice until their fate was sealed with this prickled plant. This is not a forgiving land to those foreign or unprepared for their travels.

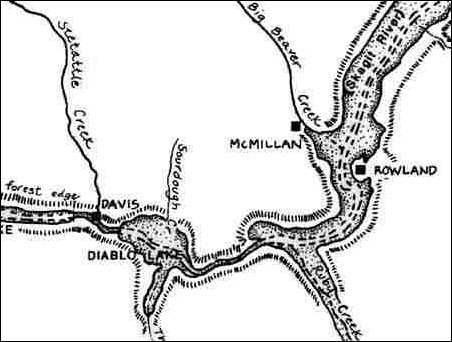

I had heard John McMillan’s name in my first round of research into the topic of fur trapping and soon started to hear stories of his cabin. All that was shared with me about the location of this cabin was that it is somewhere on the west side of Big Beaver Creek, before the marsh and after the stream.Joe and I had the advantage of hearing about first hand accounts of finding the homestead through the use of roughly drawn maps and a faint trail that was previously used by McMillan and the Forest Service before Big Beaver Trail was established.

Trail map around Diablo Lake. Photo courtesy of the United States Forest Service.

We found this faint line of a trail that lead directly into a fresh patch of fluorescent green moss and downed trees. We had immediately lost the trail, but continued on to meandering through the woods experiencing the true wonder of wandering among the old growth.

If you’ve never been in an old growth forest, it is important to understand the imagery here. Western Red Cedars as wide as the length of your body and taller than your eye can see, tower above you with equally sized Douglas fir. There is not much sunlight down at the floor of this forest as you are nicely shaded by the year round needles of these immense trees. All that covers the floor are remains of these now brown needles and various degrees of decay with the occasional bright spot of moss or patch of wild ginger that made for easy snacking.

Every once in a while, we’d pick up the trail again in a very odd way of just happening to come across it, and then quickly loose it again as a fresh blowdown or new growth of cedars, hemlocks and Douglas fir obscured the trail. This was in fact a beautiful forest, a desolate forest and one with character of thousands of years of experience.

After loosing the trail a number of times, we decided it best to separate a little bit in order to cover more ground and give ourselves a better chance at finding the cabin. As we drifted further and further apart, I found myself in a tangle of tightly grown trees. Eventually deciding to retreat to the clear forest floor of the old growth cedar grove, I stepped right next to an enamel rinsing pot. Looking around a bit more, I found an old stove grate, another enamel dish and then finally the foundation of the old cabin.

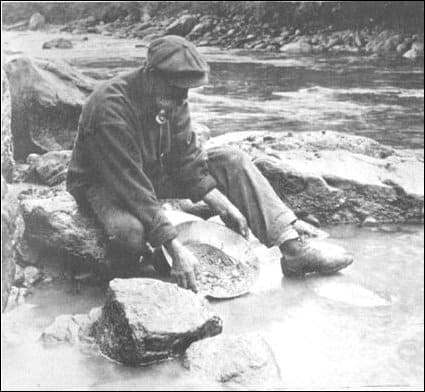

The life of a trapper is filled with long days and nights in the dead of winter where hiking from trap to trap seems like the only relief from work. John McMillan trapped mostly in the Big Beaver drainage and would trade his furs for supplies using the Skagit-Hope trail to Fort Hope in British Columbia. During the off seasons of trapping, these homesteaders had to piece a living together from various types of work. Often times a trapper would also be a logger, an inn keeper a miner and any other pieces that could fit the puzzle. McMillan and his wife were proud owners of a roadhouse when he first got to the Skagit Valley, but decided to trade this house for a cabin up Big Beaver Creek that was built by Tommy Rowland (another prevalent homesteader in the area).

John McMillan was in and out of the rugged country he called home. He began to give up on the hardships of the prospecting life and trapping and his home life was not at all stable so he left to the city. His final return was when he became deathly ill and desired to live his last moments in his homestead on Big Beaver. He was laid to rest on July 29, 1922 with a headstone on the outskirts of his cabin marking his grave.

Although we had been told that John’s headstone was still visible on the perimeter of his cabin, after a few hours of searching, we decided time had done its work and covered the grave marker with forest debris.

Returning to the established trail, both Joe and I had thoughts and questions running through our heads about what life would actually be like out in this rugged landscape. Piecing a life together through any means possible would be rewarding but also a constant battle. What made John McMillan decide to live his last moments in this secluded and intense landscape? Would I choose to lay in my death bed alone, unknowing if someone would show up to eventually bury me?

https://youtu.be/Eqog9VZk56c

John did in fact get buried by a group of close friends that built his coffin and laid him to rest with a cedar shake headstone. How they knew to come, I have not discovered, but their friendship and respect for John McMillan was apparent.

I still have questions though, and this landscape has an endless amount of stories to tell. Sometimes its just a matter of traveling the paths of ghosts.