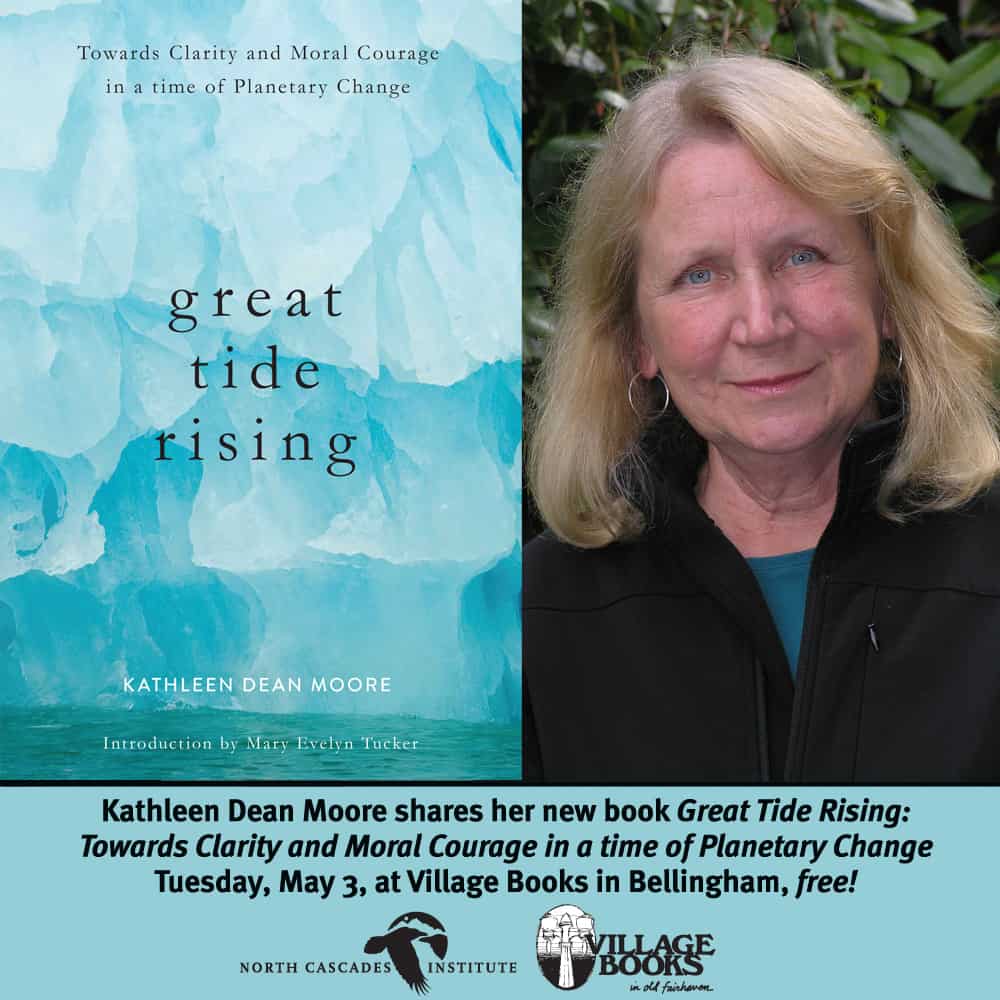

Great Tide Rising: Toward Moral Courage in a Time of Planetary Change

Join North Cascades Institute at Village Books in Bellingham on May 3 at 7 pm for a free reading by Kathleen Dean Moore from her new book Great Tide Rising: Toward Moral Courage in a Time of Planetary Change.

Oregon writer Kathleen Dean Moore founded her reputation as a top-notch writer through several books that gracefully combined natural history, philosophy and meditations on being human, as in Riverwalking, Pine Island Paradox and Wild Comfort. Her focus took an urgent turn in 2011 with Moral Ground: Ethical Action for a Planet in Peril, a collection of essays she co-edited featuring essays from thought leaders like E.O. Wilson, Thomas Friedman, bell hooks and the Dalai Lama on the moral responsibilities we have for safeguarding Planet Earth.

“Moral Ground made the case that the threatened climate catastrophe was a moral catastrophe, and it called for a strong moral response based on our love for the children, commitment to social justice and a reverence for life,” she explained to me recently in an email. “After the book was published, I hit the road [including a reading at the Whatcom Museum during their 2013 “Vanishing Ice” exhibit]. For three years, I spoke in every place that would have me – church basements to town plazas – listening to the people who so deeply cared, wrestling with the questions they asked, watching the world change.”

Her new book Great Tide Rising: Toward Moral Courage in a Time of Planetary Change is a result of her climate change “listening tour,” a deeply-felt manifesto that ponders, as Moore explained, “How can I bring some clarity to the hard questions? How can we all find the courage and the communities of caring that make it possible to keep trying? How is it possible to open peoples’ hearts without breaking them?”

With sections along the lines of “A Call to Care,” “A Call to Witness” and “A Call to Act,” Moore has written a guidebook for modern day environmentalists and climate activists that is both grave and restorative.

“Writing Great Tide Rising lifted my spirits,” the writer told me, “because when you look for them, there are logical and creative answers to the hardest questions. When you look for them, there are people all around the globe who are standing up to the forces that would wreck the world. And when you look around, you see that there is so much worth saving. These are the stories I wanted to tell.”

Here’s an excerpt from Moore’s new book:

And so we come to the obligatory question about hope.

“Is there a reason to hope?” asked the bearded man who had waved his hand like a flag. . . .

“What do you mean by the question?” I asked. That’s a response that makes people hate philosophers.

Do you mean, is there good reason to think that the Earth can avoid sweeping extinctions and disruption of the systems that support our life-ways? If that’s the question, the answer increasingly is no, not really. . . .

However, it turns out that the bearded man in the audience had quite a different interest in hope. When he clarified his question, this is what he said, “There is no hope. Nothing I do will make any difference. I can’t save the world from climate change or ecological collapse. So I’ll just keep on buyin’ and burnin’ the way I always have. There’s no point in change to no effect.” What do I say to that?

Well, like any philosophy professor, I called him out: “What the heck kind of reasoning is that? You don’t do the right thing because it will have good results. You do the right thing because you believe it’s the right thing. . . .

Consider the moral abdication of blind hope: If everything is going to turn out okay, regardless of what I do, then I am under no obligation to do anything, because nothing I do will make a difference. Consider the moral abdication of blinding despair: If everything is going to go to hell, regardless of what I do, then I am under no obligation to do anything, because nothing I do will make a difference. Blind hope or blinding despair? Either way, I don’t have to do anything. I’m off the hook.

But notice that this is a logical fallacy – the fallacy of false dichotomy. It’s not true that our only options are hope and despair. Between them is a broad middle ground, which is acting from neither hope nor despair; it has nothing to do with future consequences. This broad middle ground is acting with integrity. Integrity: like integer, a whole number, from integritatem, wholeness, a consistency between what one believes and what one does. . . .

The times call for integrity. The times call for the courage to refute our own bad arguments and renounce our own bad faith. We are called to live lives we believe in, even if a life of integrity is very different, let us suppose radically different, from how we live now. People of integrity live gratefully because they believe that life is a gift. They act reverently, because they believe the world is sacred. They live simply, because they don’t believe in taking more than their fair share. They act lovingly toward the world, because they love it. . . .

Standing at the podium, trying to steady my voice, trying to keep from crying, here’s what I said to the bearded man who asked about hope: Each of us has the power to make our life into a work of art that expresses our deepest values. Don’t ask, will my acts save the world? Maybe they won’t. But ask, are my actions consistent with what I most deeply believe is right and good? This is our calling, the calling for you and me and everybody else in the room: To do what is right, even if it does no good; to celebrate and care for the world, even if its fate breaks our hearts.

And here’s the paradox of hope. That as we move beyond empty optimism and choose to live the lives we believe in, hope becomes transformed into something else entirely. It becomes stubborn, defiant courage. It becomes principled clarity. And when courageous-hearted, clear-minded people find one another, it becomes a powerful creative force for social change – a great rising tide of affirmation of justice and human decency and shared thriving.