Donut Hole: Threats to the Skagit Loom North of the Border

Since time immemorial, the Skagit River has been a life-giving watershed for countless organisms that live in and along the banks of its milky-blue waters. The river’s name derives from the Indigenous people of Upper and Lower Skagit territories who have traveled up and down these waterways, sustaining themselves physically and spiritually on its bountiful salmon runs for generations.

Today, the Skagit remains the largest and most biologically important watershed in the Puget Sound region. The river continues to support runs of all five native salmon species as well as Steelhead (Oncorhynchus. m. irideus), Coastal Cutthroat (Oncorhynchus clarkii clarkii)and endangered Bull Trout (Salvelinus confluentus). The healthy fish populations attract one of the largest wintering Bald Eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) migrations in the Lower 48 with 600-800 birds finding roost along the river annually. The Skagit is also a year-round home to beavers, waterfowl and countless other creatures that find homes, food and water along its banks.

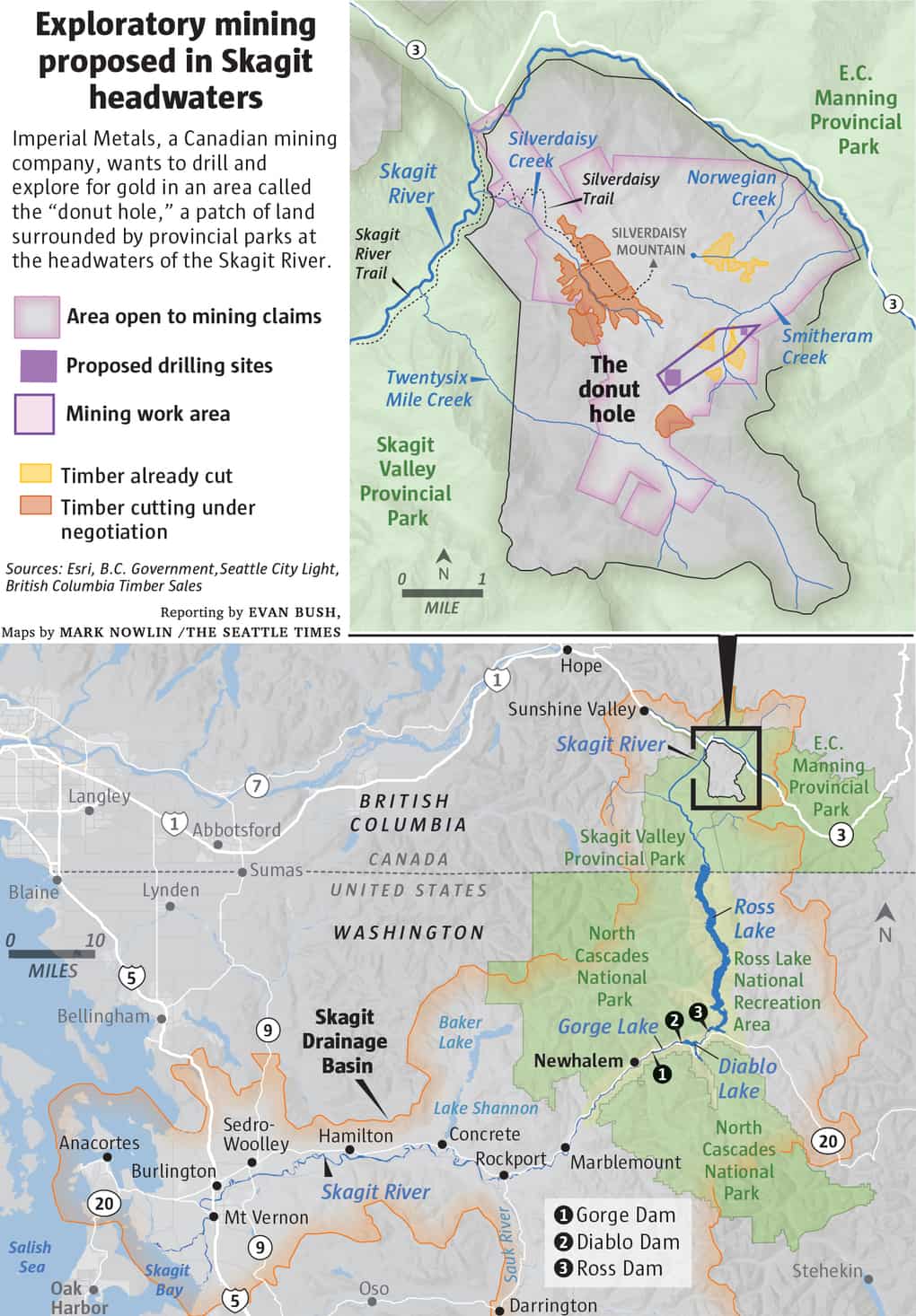

In addition to wildlife, the Skagit River supports recreational and commercial boating and fishing, irrigation for agriculture, and nearly 20 percent of Seattle’s low-carbon energy from Ross, Diablo, and Gorge Dams. With so many diverse, and at times competing, stakeholders it is not a stretch to say the the Skagit River watershed is the lifeblood of our region. In 1978, the United States Congress recognized the river’s importance by designating it one of the Nation’s first Wild and Scenic Rivers. However, a lapse in conservation of this watershed north of the U.S. boarder in Canada could threaten the integrity of our watershed for generations to come.

A majority of the Skagit River’s 150-mile run lies within the United States and is protected by its Wild and Scenic designation, as well as the North Cascades National Park Complex. However, the river’s headwaters and the first leg of its journey to the Salish Sea reside north the international boarder in British Columbia. There, E.C. Manning Provincial Park and Skagit Valley Provincial Park combine to protect much of the river’s headwaters, with the exception of a Manhattan-sized gap of land between the two parks that is commonly referred to as the “Donut Hole”. This area is now at the center of a land-use battle that threatens international treaty and the future of the Skagit Watershed.

It was revealed in March that a Canadian mining company, Imperial Metals, has applied for an exploratory mining permit on Silverdaisy Mountain inside the disputed zone.

Disputes over international land and water rights on the Skagit between the U.S. and Canada date back to the 1940s, when plans to increase the size of Ross Dam, and thus the reservoir behind it, threatened to flood 5,000 acres of Canadian land north of the boarder. British Colombians objected and pushed back, resulting in decades of stalemate over the river’s fate. The matter was ultimately resolved in 1984 when the city of Seattle agreed to not increase the size of the dam in exchange for cheap hydropower from Canada until 2065. In addition, the two governments formed the Skagit Environmental Endowment Commission (SEEC) with a mission to work collectively to protect the watershed for conservation and recreation. The deal was finalized by the High Ross Treaty and was signed by both federal governments.

All seemed well on both sides of the boarder, until last summer when it was discovered that clear-cutting had begun within the donut hole in what many believed was a violation of the 1984 treaty. Conservationists have long feared that logging roads in the zone would make the area more attractive to mining interests, and now those interests are making their intentions known.

To make matters worse, Imperial Metals is the operator of the Mount Polley Mine, best known for the Mount Polley Mine disaster in 2014 which allowed 2.6 billion gallons of gold and copper mine tailings to be released into Polley Lake, Hazeltine Creek, and the nearby Quesnel Lake. Many environmentalists believe a similar disaster on the Skagit would result in a death nail for already struggling salmon populations and the dozens of species that depend on them, not the least of which is resident Puget Sound Orcas. Heavy metals, like copper, are toxic to salmon damaging their sense of smell, imperative to their ability to return to native streams for spawning.

Although mining the headwaters of the Skagit is closer than ever, the deal is far from final. Even if the exploratory permit is granted, it would not allow Imperial Metals to develop a full-scale operation. The odds of Imperial Metals finding any materials worth developing are low, and the permitting process to so would likely be long and expensive given the importance of the river, the treaty in place, and the company’s environmental safety record. In B.C. only 1 in 3,000 exploratory permits ever result in a full-scale mine. Still, even exploritory mines can pose a threat to water quality, and it is important that people downriver stay vigilant and voice their concerns.

In response the permit application, Seattle Mayor Jenny Durkan has sent a letter to B.C. Premier Jon Horgen and issued a statement saying:

“The City of Seattle is very concerned about the proposed actions to allow mining in the Silverdaisy area in the Upper Skagit Watershed. As with potential logging, mining in this area would threaten the environment, undermine our investments in salmon and bull trout recovery, and harm the integrity of a watershed that is critical to millions of people in Seattle and our region.”

Currently, nearly 100 elected officials, tribal leaders and environmental organizations on both sides of the boarder have voiced their opposition to this permit, including both Washington Senators and Governor Jay Inslee. In addition, the SEEC is currently working to convince the B.C. government to halt mining operations and facilitate the purchase of remaining timber and mineral rights in the area to finally preserve the land within the donut hole.

If you would like to take action, you can write a letter to Washington’s elected officials thanking them for their support and urging them to keep up the pressure on B.C. Premier Jon Horgan to deny the permit here.