Adventure in the Gorge Lake draw-down

Fifty years ago, returning visitors to the Upper Skagit Valley may have asked the question “Where has the river gone?” With the 1961 completion of the 300-foot tall Gorge Dam, the turbulent waters of the Skagit River were replaced by a placid blue-green ribbon of a lake named after the rugged terrain that surrounds it. On most days, visitors to North Cascades National Park can enjoy views of Gorge Lake from the many viewpoints along State Route 20 or boat the three miles of flat water from the town of Diablo to the dam itself. But today wasn’t like most days.

Bouck Lake is up there…somewhere.

Bouck Lake is up there…somewhere.

Earlier this summer, my friend John Harter and I set our adventuring sights on Bouck Lake. The plan was to canoe down Gorge Lake to the Bouck Creek drainage, tie up the boat, and then scramble up 3,000 feet of cliff-filled forest. There was no trail and neither of knew of anyone who had attempted the hike before. John and I couldn’t even agree on where exactly the lake was hiding on the steep forested hillside! It was going to be a fun adventure. As the day of our hike neared, our ambitious plan got even more challenging: Gorge Lake disappeared. Our approach to the beginning of our hike was gone.

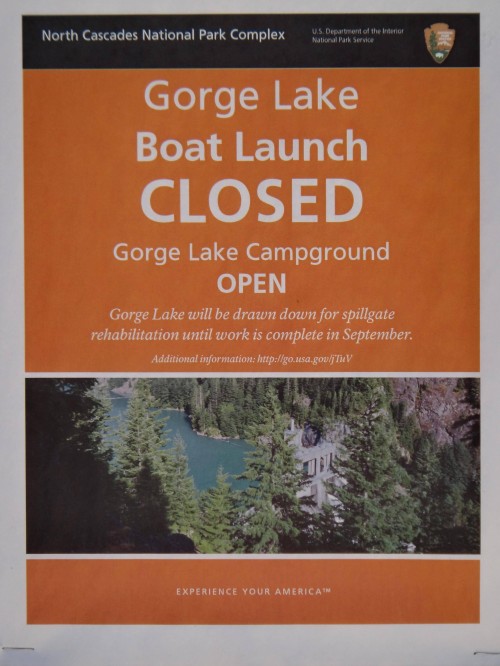

A sign posted at the Gorge Lake boat launch

A sign posted at the Gorge Lake boat launch

According to the Seattle City Light website, the level of Gorge Lake had been lowered significantly to accommodate rehabilitation work on the spillgates of the dam itself. While the lower water level was great for the Seattle City Light workers replacing seals and repainting the spillgates, our lazy paddle to and from our hike had become a Class-IV whitewater rapid. Neither John nor I felt comfortable canoeing the whitewater and I couldn’t convince John to swim across the 200 yards of calm, glacially-chilled water at the bottom of Bouck Creek. So our plans to visit Bouck Lake were scrapped in favor of exploring the land below the lake—the historical shoreline of the Skagit River.

The rapids

The rapids

Heading downhill from State Route 20 following the Ketchum Creek drainage, John and I picked our way through the forest to the bank of the river. The soft mix of mud, sand, silt, and glacial flour, having been exposed to the warm summer sun, had dried and cracked creating an alien landscape of grays, browns, and blacks. Tree stumps topped with mounds of sediment emerged from the fractured ground. An odd smell lingered in the air. Small seeps and streams cut winding paths through the muck. Clouds of suspended particulate floated by in the green water of the river. It was a sight to see.

The author picks his way along the Skagit River through silt and sticks

The author picks his way along the Skagit River through silt and sticks

Wading through ankle-grabbing mud we tramped upstream to try to catch a glimpse of the river as it was before the dam: free-flowing, wild, and awesome. The river in this area was reportedly so rough prior to the construction of gorge Dam that salmon, perhaps the mightiest of all river travelers, could not make it any further upstream. And just like the salmon, the rugged terrain thwarted our quest to the rapids and beyond. As John and I stood above the river struggling to look up stream, I thought not only of the salmon, but also of the many hardy men and women who traversed this landscape before us. What were their struggles? What were their stories?

How long has this sign been underwater?

How long has this sign been underwater?

The silty muck and sun-warmed rocks held some vague answers to my questions in the form of objects left behind: Ceramic wire insulators long detached from their wooden roosts. Rusty braided cables dangling off cliffs. Pull-tab beer cans with their labels scoured clean by sand. The tangled fishing line of a frustrated angler. A road sign far from its station outside of a dynamited passage. Puzzle pieces of a story that will never gain be whole. A hundred or more years of history preserved by the lake only now uncovered by the retreat of a man-made lake.

John takes a break from boulder hopping

John takes a break from boulder hopping

As we traveled downstream toward Gorge Dam our path along the shoreline became more and more tenuous. The boulders lining the shore became bigger; we clawed our way up slippery slopes, digging our fingers into the mud; and climbed over and around stacks of massive logs punctured by rusted spikes. I hoped to reach Gorge Dam, peer into the green water, and perhaps discern the shadow of an older dam beneath the surface. Was the original wooden crib structure from the early 1900s lurking just below the surface?

Gorge Dam and mysterious pilings (rectangular platforms on left)

Gorge Dam and mysterious pilings (rectangular platforms on left)

Finally, after much effort, we stood atop an outcrop and gazed out at Gorge Dam, its upper third exposed to the midday sun. Two rectangular platforms sat motionless in the water, apparently anchored to the bottom of the lake. Could they be the remnants of a smaller dam or perhaps the pilings of an old bridge? We sat in the shade eating an apple, pondering the sight before us. Workers climbed up and down the dam like ants, dwarfed by the concrete structure and the mountains around them. After a while we turned our tired feet uphill. Leaving behind this silt-encrusted world of the past with more questions than answers, we headed back to State Route 20.

Heading home

Heading home

Although we didn’t make it to Bouck Lake we had still gone on quite a journey. Standing under an overhanging cliff, John wondered aloud when the last time a human traversed the wild shores of the section of river. Could it really be that we were the first people to visit this underwater moonscape in 25, 50, or 100 years? Come September and the return of Gorge Lake, when will be the next time people get their feet stuck in this silty mud and wonder about the rusted relics below the green water?

Leading photo: Gorge Lake, empty of water. All photos by Nick Mikula and John HarterNick Mikula graduated from North Cascade Institute and Western Washington University’s Environmental Education graduate program in 2012. He is currently studying human and ecological communities, playing the guitar, and exploring the land between the Salish Sea and the Cascade Crest.

I was only 8 years old when we (my dad and several other workers from Seattle City Light) made the hike to Bouck Lake for a fishing trip in 1963 – the lake was stocked by SCL and was frozen over until late July. The hike was difficult (as I recall it was only a couple miles but it was mostly vertical and took about 8 hours) and the only trail was marked by red ribbons. Only about one party made the hike per year.

We began at dawn by climbing down a treacherous rock slide from the highway to Gorge lake, which we crossed by raft to a tiny beach on the other side. It was almost straight up and slow going. I remember taking about 30 minutes just to get through a few feet of thicket an hour into the hike. We paralleled a creek part of the way. As we approached the lake by late afternoon there was another huge rockslide in front of us with boulders the size of SUVs that would slightly rock when you climbed over them. The last leg was the most difficult and dangerous. At the top of the rockslide we had to veer left (there was a solid rock wall at the top of the slide) with about a 500 foot dropoff behind us and a dried creek bed in front of us. The creek bed was comprised of jagged and slippery rock with a very steep grade and was at least 100 yards in length. It was very scary because if you fell backwards you could have went over the dropoff (it was that steep) and those rocks would probably have broken most your bones anyway – we were very careful.

When we got to the top we discovered a crystal clear lake surrounded by some cliffs on the right side (I remember a cave) and a large glacier behind it and to the left. Bear tracks were prevalent. The fishing was fantastic as we found out a shiny hook sometimes worked as well as salmon eggs.

My dad and I made the trip again in 1973 (we got sick on the hike back from drinking water from the creek) but I have heard nothing about any trips since then. I wonder if SCL still maintains the lake.

You had the right idea, you must boat to the trailhead, and make your way up the mountain from Gorge Lake. There are 2 ways to get there, both are 5/5 hiking skills. The fish are well established, since they have so many safe places to spawn. You could fish with a pitchfork, but you’re not getting them out very easily 😉

If you don’t like leaving the way you came, or don’t have a boat, cross Gorge dam and get the to end of the southward river “road”. You will require permission to be in that area. But to the left is another way to make it to the lake. A much longer hike, and better done in August to avoid all the snow. Don’t bring your dog, there’s too many bears.

If you use the river road to reach the lake from the south, look across the river to the hwy 20 tunnel. an ancient mining path and bridgework dubbed ‘Devils Pass’ is still visible. Imagine packmules navigating it.

I climbed up to Bouck Lake in about 1974 with two others, and it was as the two other commentators described. We rafted across Gorge Lake, and climbed about 8 hours to do the two or so miles. We caught and released cutthroat trout by the dozens, and since this was a drought year, we could walk the shoreline easily, avoiding the buckbrush lining the usual shoreline. We were in our early 20’s and in excellent shape. This is a trip for expert outdoorsmen in excellent shape. No one else should try it.