We don't know what we've already lost: A road trip

As much as we love North Cascadian landscapes, we here at the Institute are still called to visit and experience other amazing places on our planet. We publish accounts of the places Institute staff and graduate students visit in our Road Trip series.

By David “Hutch” Hutchison, naturalist at the Institute.

We paddle our small boats upon the black still water, reflecting a mirror image of the great sandstone walls rising perpendicularly from its depth. The mountains beyond covered in snow on this early March morning provide a stunning backdrop and increase our sense of remoteness. Each paddle stroke brings us further into the land of sandstone canyons, the land of water reclamation, of summer recreation, and the great pause which the Colorado River makes along its journey to the Sea of Cortez. We have entered a land of contrast; nature and human design merge here in beauty and tragedy, revealing much, while obscuring much more.

Lake Powell, so named in honor of the first European/American expedition to explore the length of the Green and Colorado Rivers, remains a beautiful place despite the changes made by the Glen Canyon dam. During our six days on the waterway in sea kayaks, we explore only a relatively small area of this vast reservoir. The tributaries and channels of the watershed are now backfilled creating a labyrinth of flat, motionless water, a maze of passages which cry out for the slow exploration of motorless boating. At this time of year, the houseboats and party barges remain quietly moored in their harbors and our only companions are the occasional early-rising fisherman buzzing to a secret spot among the myriad twists of side-canyons and channels which make these hectares of water feel so expansive and at once so intimate.

We journey with two good friends, former grad students, who are here as much to scout a trip for their university in southern Arizona, as for personal vacation. We join them not only for the experience of paddling this lake but to reconnect with old friends. As we paddle off from the busy landing of Hall’s Crossing, we quickly fall from the hectic travel and logistics of getting ready for such a journey, and settle into our cockpits and the rhythm of simply being on the water.

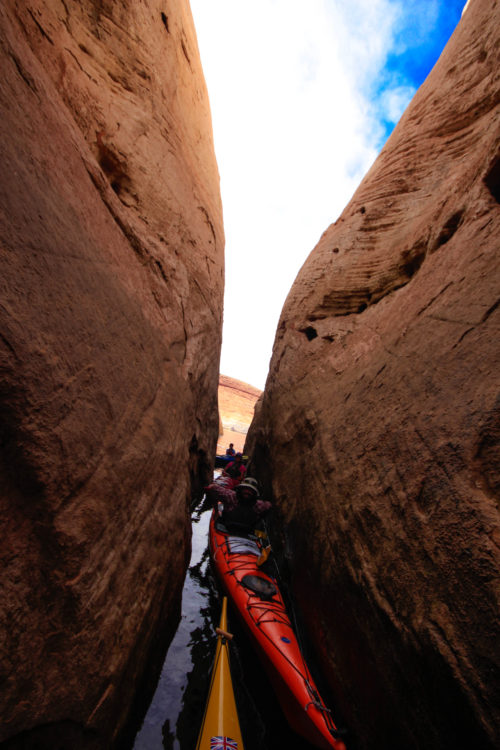

As we explore new side-canyons, the vast walls close in and bring the open expanse of the main channel into contrast, and ratchet up the wow factor. The distinct personality of each area slowly reveals itself after paddling around the first turn, then onto the next and the one after. The walls rise abruptly out of the water, as if created whole rather than by the powers of erosion. The smooth sandstone flows in layers of rose, buff, mahogany, and cream. Edward Abbey’s description of the cliffs in his love letter memoire, Desert Solitaire, utterly captures it for me: melting ice cream – Neapolitan ice cream. The soft focus, the blurred edges of transition, the smooth roundness give a sensual, almost culinary, appeal to the hallways, especially around the magic hours of sunrise and sunset.

Because Glen Canyon is back filled to pool-like stillness by the dam we have for a moment paused with this water on its journey toward the sea – a journey which it no longer completes. We pause too, as if entering a Gothic cathedral from the brightness of day, hushed to a reverent silence waiting for our eyes to adjust, and take it all in. The creator here cannot be measured in generations of stone-mason, but in geological epochs, which challenges the human mind in contemplation. I break the silence of this church by checking out the acoustics, singing the only opera I know — the reverb, not too bad.

We spend our days exploring where the serpentine canyons lead us. We look for suitable camping places as much for ourselves as for the group which will come next spring. We follow the ever narrowing ribbons of water until the water ends and the sand and mud begin. We pull ourselves and our boats out as best we can and find a way up the twisting bends through shoe-swallowing mud searching for Ancient Puebloan ruins, sinkholes, slot canyons, or simply needing an excuse to get out of the boat and stretch the legs.

After sitting on our backsides for a few days, our curiosity of what this watery wonderland looks like from above becomes too much to resist. We scramble up the Slickrock, so named not for the gripping rubber shoes we now wear, but for the trouble given to iron shod horses and the cowboys who rode them. Rubber seems to work just fine and we make it up some steep terrain that upon first blush, would give us some trouble. We work our way up by winding back and forth, not really following any trail except for what seems to make the most sense. At the top we’re rewarded with some stunning views of the Henry Mountains, still showing last week’s snow, the emerald lake below, and the delicious lunch we packed earlier.

Our paddle on Lake Powel introduced me to iconic images of Utah’s Colorado Plateau and also set the stage for an introduction of another sort. Shortly after finishing our week’s journey upon the waters, a friend loaned me a copy of Edward Abbey’s Desert Solitaire, in which he dedicates a chapter of the book to his own journey through the same sandstone canyons just a few short months before the dam was completed—likely one of the last documented floats before the flood.

More poignant than Abbey’s description of traveling the river — the rhythms and routines established, the loss of any sense of time / day of week, and connection with the wild on its terms — is his sense of grief over this canyon’s fate to which he cannot quite give voice. As they float past side canyons and temples of sandstone two thousand feet above them, their thoughts never stray far from the inevitable, that this narrow path of water cutting its channel through millions of years of sandstone will soon be buried in silt, mud, sand, and water. They prefer to focus on the present and give the river bank, side canyons, and rapids their full attention — to experience it as is. Who could blame them? For what good could possibly come of dwelling in despair of the inevitable?

Abbey’s eulogy for the canyon leaves me with an aching sense of loss, especially after seeing the locations he describes so transformed. He mourns not only for the ancient cliff dwellings, the petroglyphs carefully tapped onto mural walls, the side canyons with their labyrinthine holes carved over millennia through the soft Navajo sandstone, the “Music Temple” named so by Powell’s 1869 expedition for its acoustical mysteries. He also mourns the loss of true wilderness where access is hard won through footsteps over dry stone or a week’s travel by paddle boat from the nearest road. He asks, “All things excellent are as difficult as they are rare, said a wise man. If so, what happens to excellence when we remove the difficulty and the rarity?”

This remains the quintessential Abbey question, what are we losing in our quest to develop the world, to remove obstacles in order to gain access? His answer is clear, and with tongue in cheek would say that we’ve got a great world going here, except for all these damn humans. His judgment remains slightly more complex however; he needs human company as much as anyone despite seeking his solitude in the Utah desert. He would also be the first to remind us that humans are the only animal to operate a bulldozer.

There remains a conflict here for me. I know that where I am and what I’m seeing is as a result of human intervention into natural processes. From my cockpit, I am 400 feet above the natural river bed now filled with mud, silt and sand. But what is left here is still stunningly, starkly, beautiful to behold and still offers some challenge to explore, at least in the manner we’ve chosen.

I would feel differently about my experience in Glen Canyon during party boat season, the number bobbing in Hall’s Crossing marina awaiting their owners’ summer vacation is staggering. One of the great joys of wilderness travel is the chance to be, or nearly be, alone. With even half of these boats underway, we would have to run such a gauntlet of traffic as to scare away much of the magic of the place – not in what we see necessarily but in how we experience it.

If I had discovered Abbey before dipping my paddle into Glen Canyon waters, I am sure that I would still have been captured by his storytelling, his sense of awe, his humor, and might have agreed with his conclusions. I would have had the luxury of only his side of the story, a compelling one to be sure. I probably would have thought the lake was a terrible way to treat a good river, shrugged and forgotten about it, as I go on with my life. But, if I had only visited Lake Powell as it is today without the benefit of Abbey’s nostalgia, I might have been convinced of the lake’s necessity. I could have bought the whole dam story, its water recovery, its flood control, its opportunity for recreation and so forth. I would have been too captured by its current beauty to really ponder the possibility of what the river looked like in its pre-dam state. And, if I had to navigate the lake surrounded by house boat heaven, I would have thought, “Get me the hell out of here!”

The complexity here is the same with all projects when humans alter the landscape on such a grand scale. While we can quantify the benefits in kilowatt hours, we are left with colossal consequences of a fundamentally altered environment. No matter our intentions, these actions simply cannot be undone. In the middle 50 years of the last century our government and society was on a dam building mission across this continent. That was “progress” and of course there was money to be made, lines to pull, and consumers to connect. This same story is being played out in developing nations today. Indigenous people and their land are being swept aside for the sake of progress. While we may be able to justify what is gained as a result of this effort, just as I could see the beauty of Lake Powell, it is impossible for us to know what is lost once it’s gone.

Abbey concludes; “The new dam, of course, will improve things. If ever filled it will back water to within sight of the bridge (Rainbow Bridge), transforming what was formerly an adventure to a routine motorboat excursion. Those who see it then will not understand that half the beauty of Rainbow Bridge lay in its remoteness.” I am left pondering my own understanding, and grateful that I have experienced it through Abbey’s eyes as well as my own.

No matter where you are, get out there, and get out of your car, before it changes into something entirely different… And while you are at it, work to preserve and protect those things you love.