A Trip to the Olympic Peninsula

Come every fall, winter and spring quarter, the graduate students in residency at the Environmental Learning Center leave for a long weekend dubbed the “Natural History Retreat.” It is a chance to explore a novel, neighboring ecosystem beyond the North Cascades we teach about and love on a daily basis. Last autumn, in the midst of a government shutdown, we quickly cavorted to the Methow Valley; in winter, we slept, to the extent we were able, in hard-earned snow shelters on Mt. Rainier’s Paradise. This mid-June, we headed for the one Washington national park we had yet to discover: Olympic.

But backup for a sec. Before it seems grad school is all fun ‘n’ games, it’s essential to clarify that the term “retreat” is a bit of a misnomer. Try “concentrated, highly efficient learning experience” instead. There were no hot tubs nor Swedish massages. Rather, like wolverines — those elusive weasels capable of covering six miles per hour whether traversing rivers, flatlands, or the steepest vertical relief — we were on a mission to cover as much territory in as little an amount of time as possible. In three days, we traveled from the Environmental Learning Center to Port Townsend, and eventually to the Hoh Rainforest, pit-stopping along the way to engage in multiple natural and cultural activities.

Inside Port Townsend’s Northwest Maritime Center. Smells so good, like wood and varnish and salt. Photo by author.

Inside Port Townsend’s Northwest Maritime Center. Smells so good, like wood and varnish and salt. Photo by author.

After a four-hour long end-of-season Mountain School debrief, we zoomed to sea level to catch the ferry out of Coupeville on Whidbey Island. Before we knew it, we were attired in orange dry suits and talking like pirates on a long boat in Port Townsend. We sailed and rowed around Port Townsend Bay, captained by Kelley Watson, former commercial salmon fisherman and organizer of the Girls Boat Project, and assisted by Chandlery Associate Alicia Dominguez. The quick trip was a success, and our tiny craft failed to collide with the giant ferries or picturesque sailboats in the midst of their weekly Friday night race. A graduate student in education herself, Watson told us Port Townsend had recently passed the “Maritime Discovery School Initiative.” As part of the community’s commitment to place-based education, all students would get a first-hand exposure to the maritime trades. Our collective graduate cohort eyebrows raised in unison as we heave-hoed through the salty sea: Jobs?

Down from the mountains, on the sea: From L to R: Katie Komorowski, Sarah Stephens, Elissa Kobrin, Samantha Hale, Joshua Porter, and Alicia Dominguez. Photo by author.

Down from the mountains, on the sea: From L to R: Katie Komorowski, Sarah Stephens, Elissa Kobrin, Samantha Hale, Joshua Porter, and Alicia Dominguez. Photo by author.

Totally pirate. Photo by author.

Totally pirate. Photo by author.

Work was involved. From L to R (faces): Joshua Porter, Annabel Connelly, Tyler Chisholm, Katie Komorowski. Photo by author.

Work was involved. From L to R (faces): Joshua Porter, Annabel Connelly, Tyler Chisholm, Katie Komorowski. Photo by author.

The continuity and cohesion of our graduate program was in full effect as we descended on the lovely home of Lee Whitford, a graduate of Cohort 2 and instructor of North Cascades Institute’s mycology field programs. Lee graciously made us a locally-based seafood stew of freshly-caught crab, mussels, clams and fish. We definitely felt retreated.

After an evening steeped in brine and Zephyr, we headed westward across the top of the peninsula and into the heart of Makah tribal country. Our first stop was the Makah Cultural and Research Center in Neah Bay, which opened in 1979 to showcase the thousands of artifacts unearthed from a Makah Village at Lake Ozette that had been buried by a mudslide around 1750. Geologists think an earthquake caused the massive slide; in 1970 a severe winter storm eroded the banks, bringing to light a glimpse of Makah daily life before European arrival in 1788. The excavation was an intensive process: mapped in two-meter squares and using ocean water from pumps, rather than the potentially destructive shovels, trowels and brooms, to unbury approximately 55,000 artifacts. Each piece was then washed, measured and recorded. Add the fact that there were zero roads to the site, and all artifacts had to be hiked, boated or helicoptered out. Between the combined efforts of the Makah, archeologists and volunteers, the site took 4,000 days spread over 11 years to unearth.

The Lake Ozette site is considered a “great opportunity” that inspired today’s museum. As an interpretive sign reads: “….mudflows repeatedly have buried houses, turning them into time capsules. Subsequent water-logging has prevented decay, even of wood.” The Makah traditionally lived on 700,000 acres; their current reservation is 28,000. The exhibits, which include a replica long house, two canoes, a gray whale skeleton and thousands of daily objects from wooden boxes to fish hooks to blankets, are beautifully presented.

Strolling the museum as observers was not our only activity there, however. We were lucky to be participants, too: Graduate student Samantha Hale had lined up a workshop on making cordage from Western red cedar bark. This seemed only appropriate, considering we had been talking to Mountain School students all fall and spring about this “tree of life” and how the native tribes use it, ingeniously, for dozens of purposes from clothing to canoes. Learning to “walk the talk,” even in this small, small way, was a highlight of the retreat.

Samantha Hale uses a needle to split cedar bark into small, 1/8th inch wide strips to ready them for twisting into cordage, which can then be worn decoratively as a necklace, bracelet, anklet, etc. or used for practical purposes as rope. Our teacher, Deanne (her name comes from diya, which is the indigenous name for Neah Bay), had already harvested and prepared the bark to share with us. Photo by author.

Samantha Hale uses a needle to split cedar bark into small, 1/8th inch wide strips to ready them for twisting into cordage, which can then be worn decoratively as a necklace, bracelet, anklet, etc. or used for practical purposes as rope. Our teacher, Deanne (her name comes from diya, which is the indigenous name for Neah Bay), had already harvested and prepared the bark to share with us. Photo by author.

Katie Komorowski, with her Western red cedar bark-colored hair, demonstrates the technique of holding the cedar strands in one’s mouth and twisting from there. There were ten of us wandering around the room doing this. Photo by author.

Katie Komorowski, with her Western red cedar bark-colored hair, demonstrates the technique of holding the cedar strands in one’s mouth and twisting from there. There were ten of us wandering around the room doing this. Photo by author.

Adorned with our new, handmade creations, we hustled out to Cape Flattery, the most northwest point in the Lower 48 states. Numerous details made this coastal rain forest vibrate with life, such as the delicate ivory urns of the salal already transforming to berries (up at 1200′ elevation, they were still opening their last buds) and the crystalline aqua of the Pacific as it swirled in the sea caves.

Soon, these forming fruits, shown here covered in slightly sticky, rose-colored hairs, will mature into indigo-black, edible berries. Photo by author.

Soon, these forming fruits, shown here covered in slightly sticky, rose-colored hairs, will mature into indigo-black, edible berries. Photo by author.

Though Cape Flattery’s views were impressive, we were craving sand between our toes and wet pant cuffs. We’d descended from the shadows of North Cascadian peaks, yet many of us had, pre-residency, come from the coast. The Sirens called, and we soon found ourselves, after a flat and muddy two-mile hike, setting up camp at Shi Shi Beach. The long evening was mostly spent poking around tide pools, admiring the chitins, limpets, sea stars, tiny fish, hermit crabs and sunflower anemones radiating in the same hue as a summertime Diablo Lake. The realm of the rocky intertidal sometimes feels like being on another planet – but no, it’s just the wild diversity of Earth.

This seething life isn’t always so easily pretty. Samantha Hale, lover of all things marine biology, was giddy over finding a decaying California fur seal. And she was right: it was exceptionally cool. Its skull was emerging, getting cleaned of flesh and fur by shoreline decomposers. The cycle of life was loudly on display as families of maggots, those little writhing pieces of white rice, clicked and clacked through their communal buffet. Being a naturalist is never lonely.

This is best illustrated by some samples from graduate student and co-editor of Chattermarks Elissa Kobrin’s early morning photo series, The Sea Stars of Salvador Dali:

The rocky intertidal is certainly not shy-shy about color. As author and preservationist Joseph Wood Krutch wrote: “… we have not merely escaped from something but also into something…we have joined the greatest of all communities, which is not that of man alone but of everything which shares with us the great adventure of being alive.” Photo by Elissa Kobrin.

The rocky intertidal is certainly not shy-shy about color. As author and preservationist Joseph Wood Krutch wrote: “… we have not merely escaped from something but also into something…we have joined the greatest of all communities, which is not that of man alone but of everything which shares with us the great adventure of being alive.” Photo by Elissa Kobrin.

Giant green anemones (Anthopleura zanthogrammica). According to the Monterey Bay Aquarium, “this green plantlike creature is actually an animal with algae plants living inside it. In this symbiotic relationship, the algae gain protection from snails and other grazers and don’t have to compete for living space, while the anemones gain extra nourishment from the algae in their guts. Contrary to popular opinion, this anemone’s green color is produced by the animal itself, not the algae that it eats.” Photo by Elissa Kobrin.

Giant green anemones (Anthopleura zanthogrammica). According to the Monterey Bay Aquarium, “this green plantlike creature is actually an animal with algae plants living inside it. In this symbiotic relationship, the algae gain protection from snails and other grazers and don’t have to compete for living space, while the anemones gain extra nourishment from the algae in their guts. Contrary to popular opinion, this anemone’s green color is produced by the animal itself, not the algae that it eats.” Photo by Elissa Kobrin.

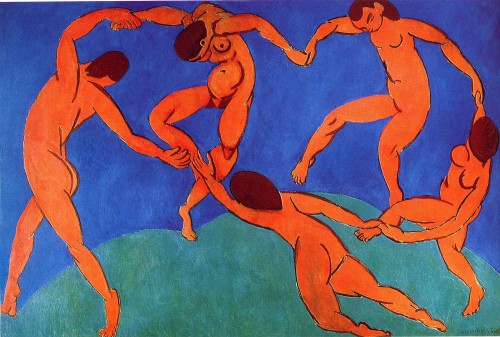

This circle of sea stars invokes Henri Matisse’s The Dance II (1910)……

This circle of sea stars invokes Henri Matisse’s The Dance II (1910)……

Non?

Non?

After driving through Forks, home of things for sale like “Twilight Firewood,” we made it to the climax of our journey, the Hoh River and Hoh Rain Forest, the green heart of Olympic National Park. It was a rapid, less-than-24-hour introduction to our sister park, but it was fun to visit a landscape that gets even more annual precipitation than does the North Cascadian ecosystem. The epiphytes were off the hook!

Shaggy and verdant: The Hall of Mosses is characterized by big leaf maples (Acer macrophyllum) blanketed in the most primitive of land plants: moss. Photo by Elissa Kobrin.

Shaggy and verdant: The Hall of Mosses is characterized by big leaf maples (Acer macrophyllum) blanketed in the most primitive of land plants: moss. Photo by Elissa Kobrin.

Student-naturalists practicing the cultivation of wonder, tiny specks within an emerald world. Photo by Elissa Kobrin.

Student-naturalists practicing the cultivation of wonder, tiny specks within an emerald world. Photo by Elissa Kobrin.

Admiring a particularly gigantic specimen of coarse woody debris. How long, we wondered, will it take for this fallen behemoth to melt back into the soil? Graduate student Tyler Chisholm (turquoise jacket) was in dead-tree heaven, having completed and presented her Natural History Project, titled “The Afterlife of Trees” only a couple days before. Photo by Elissa Kobrin.

Admiring a particularly gigantic specimen of coarse woody debris. How long, we wondered, will it take for this fallen behemoth to melt back into the soil? Graduate student Tyler Chisholm (turquoise jacket) was in dead-tree heaven, having completed and presented her Natural History Project, titled “The Afterlife of Trees” only a couple days before. Photo by Elissa Kobrin.

And so we returned to the mountains, having touched the sea, the shore, the rain forest; the past and the present, with visions of future journeys.

“OMG, the Hoh is sooooo cool!” Is nature a fan of planned obsolescence? Doubtful. The summer vacay challenge: Leave the phone at home? Photo by Elissa Kobrin.

“OMG, the Hoh is sooooo cool!” Is nature a fan of planned obsolescence? Doubtful. The summer vacay challenge: Leave the phone at home? Photo by Elissa Kobrin.

Leading photo: Secondary colors on display at the esteemed Shi Shi Beach Gallery. By Elissa Kobrin.

Katherine Renz is a graduate student in North Cascades Institute and Western Washington University’s M.Ed. program. She is eager to put her new cordage-making skills to use on some yucca whipplei.

Katherine — thanks for a great glimpse into the grad’s wonderful“concentrated, highly efficient learning experience” from the mountains to the sea and back again.