Springing into Learning: Graduate Spring Natural History Retreat

At the Institute, the graduate students of the 15th cohort (C15) have been hard at work this past year teaching Mountain School, assisting in adult programs and visiting non-profits, all while finishing assignments and trying to find some sleep! Every season though, the graduate students leave all that behind to learn from experts in the field and be fully immersed into the wilderness of the North Cascades. Last fall we worked with beavers and hawks. In the winter we dived into snow ecology and wolverines. Just last week, we ventured out on our last natural history retreat where we tracked our natural neighbors, captured native bees and kept up with all of the birds!

Tracking

Our first stop was with author, photographer and educator David Moskowitz. Since the fall we as a cohort had been using his book Wildlife of the Pacific Northwest as our go-to guide on all things tracking. Having a class with the man himself was an experience all its own.

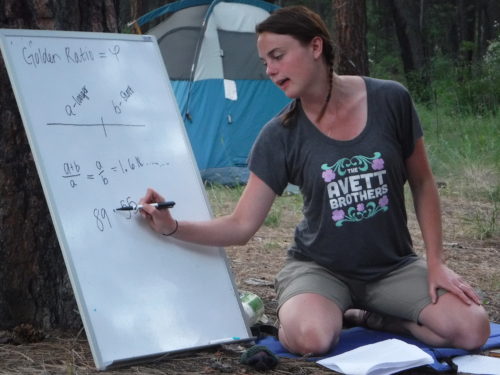

Using some of our newly acquired tracking skills.

During the winter natural history retreat we had learned the basics of tracking using snow ecology. Seeing and determining tracks without the help of the canvas of snow makes tracking much, much more difficult. To ease us into the challenge, David selected pristine tracks on a Forest Service road for small groups to “determine the story.” Often he asked us “what happened here?” and “tell me a story.” My small group felt more than confident after five minutes that we had the track of a bobcat. The size was just right, the shape was text book perfect and we knew bobcats loved to hunt in that particular micro-habitat.

After we told David our story about the bobcat, he started asking the questions we didn’t consider:

- Why would a bobcat be walking on a service road?

- Can you see the claw marks while it is walking?

- Do cats usually do that?

After five minutes of guiding us, we determined it was actually a domestic dog walking with its owner. We were initially thrown off due to the circular nature of the print, as all circular prints around that size are feline. However, domestic dogs are so varied that some have developed “cat like feet” which can throw off trackers. We then completed a few more activities before our final test of the day.

Deer carcass left by a hungry cougar during the winter.

After a short drive and a 15 minute walk, David told us about three deer carcasses in the forest. It was our job to use surrounding tracks and signs to determine what happened, how long ago was it and who did it. We scrambled into the forest and after a half hour came back with a response. Cougar during the winter?

We were correct! A cougar had hunted these deer on the nearby hill and dragged their body down into hiding while snow was still on the ground. Every track and sign, from foot prints to a pile of bones, tell a story.

Native Bees

As an environmental educator, I thought I was up-to-date with what is happening to bees. If you are unaware, nationally our honey bees are dying due to Colony Collapse Disorder. Don Rolfs introduced us to a whole new issue: native bees.

- North America is home to at lease 4,000 species of native bees. The exact number is still unknown.

- Washington State is home to at least 60 species of native bees. The exact number is still unknown.

- About half the Native Bees in Washington State or tiny black or brown bees (T-BOBBS).

- Honey Bees were introduced from Europe in the 1600’s as a source of honey and candle wax.

These were his four starting “fun facts” about how little we know about native bee populations. Over millennial our local flora has been co-evolving with native pollinators, bees being one of the most important. The European honey bee that was introduced cannot pollinate the specific flora that has been here for millenia. As Don explained: no native bees, no mountain meadows and most native plants. When we asked if native bee populations are decreasing, he gave a painful smile.

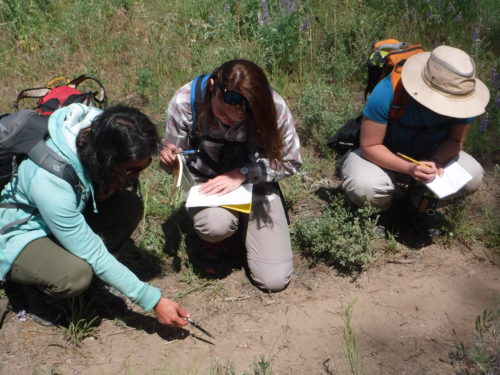

Aly Gourd observing a bee with Don Rolfs.

“We don’t even know all of the species that exist. The evolving field of native bee science is only 10 years old, so we don’t have a baseline to determine what is normal and what is not.” Don is devoting his life to being Washington State’s native bee expert. Many species that have been found don’t even have names yet!

To get a personal relationship with our native bees and to help Don’s research, we ventured out into the field to see these bees for ourselves. Even though we were out for just a morning, we caught more bees than Don had tubes for! Afterwards we got to look closely at our natural neighbors and start identifying the differences between the species.

Native bee! Notice the orange pollen it is carrying.

Birds

To say that our instructor, Joshua Porter, is a bird guy is an understatement. I wish I was poetic enough to describe in detail the pure joy he had when we started our bird class at 6:30 am that morning. Even though the sun was up, his beaming face was far brighter.

Learning about birds is far deeper than completing a Life List. When determining who is out there, it becomes a full body experience. Part hunting, part story telling, we spent a whole day following our feathered neighbors.

Spotted Towhee through spotting scope.

As a cohort we are a raucous group. Never far from a good laugh, song or dance, the fifteen of us are quite the handful. It was as if a completely different group went birding that day. Each one of us crawled through bush and fields, perfectly silent, just to get a close look at these birds.

Growing up I was always disappointed with birds, as I would much rather have dinosaurs. But taking the time to sit and observe even a single bush, I found story after story of birds in the area. All of the social drama, feeding frenzies and courtship was happening at once. Without taking the time to slow down we would have completely missed this part of our natural world.

Taking cover to observe birds.

Natural History Project Presentations

This graduate program is a non-thesis, residency master’s program in Outdoor Environmental Education. Even though we don’t have a thesis, each student is required to complete three large projects that have us developing ourselves as educators and life-long learners.

In the winter we completed our Non-Profit and Curriculum Creation projects with guidance of Institute staff. This spring each of the fifteen of us became experts in a Natural History Project of our choice. During our Natural History retreat we shared what we had learned around the fire.

Starting a fire using traditional methods.

These projects are as varied as our cohort: from mycorrhizal partnerships to ravens, from loons to math in nature. Each one of us poured our passion into one aspect of the natural world. These presentations also showcased some of the pedagogues we have learned throughout the year. Who knew you could learn so much about raven social structure by playing a game!

Playing the “Raven Territory” game as part of Hannah Newell’s natural history presentation.

Starting next week and continuing each Monday, Chattermarks will feature a different blog post from one of the graduate students about their natural history projects. Keep checking in each week to see how deep and varied the natural history of the North Cascades ecosystem is!