Letters from Yellowstone: Natural History in the Nation's Park

Letters from Yellowstone is an account of a fictional 1898 botanical survey of Yellowstone National Park, written entirely through letters. Howard Merriam, a professor from Montana is the leader of the group, which includes an entomologist, someone from the Smithsonian, an agriculturalist, and a botanist.

As Professor Merriam is setting up this field study and looking to finalize his team, he receives a letter from an A. E. Bartram at Cornell University. Bartram studies medicine and is very interested in botany, having extensively studied the Lewis expedition (currently, more commonly referred to as the Lewis and Clark expedition) for several years. Professor Merriam is delighted and extends A. E. Bartram a warm invitation to join the team. At the arrival in Yellowstone of said Bartram, however, Professor Merriam is frustrated and discouraged to find that Bartram is in fact a woman, not a man as he had previously assumed from their written correspondence.

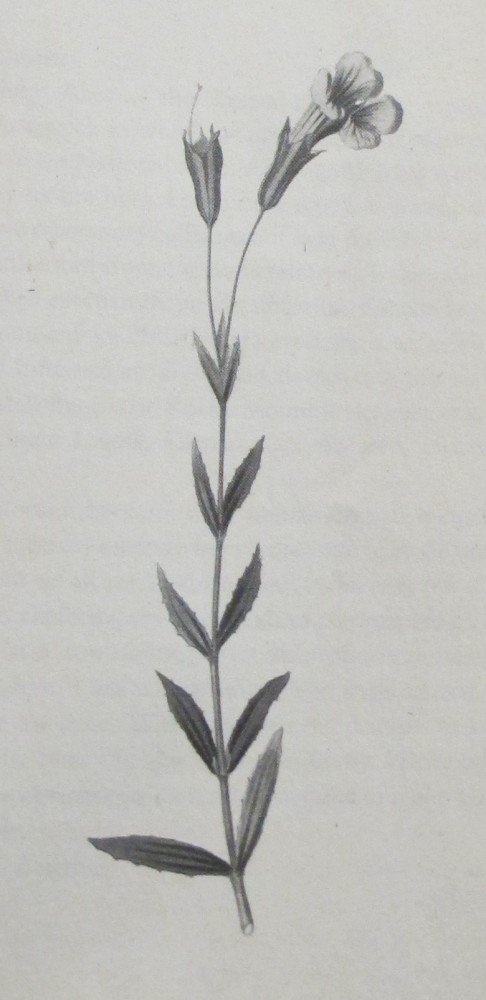

Mimulus Lewisii, or Lewis’ Monkey Flower. Illustration from the book

Mimulus Lewisii, or Lewis’ Monkey Flower. Illustration from the book

The book continues as they set out into the front-country and backcountry to draw, observe, record, name, and take specimens of as many plants as they can find. This is not, however, a story without adventure—throughout their summer, the characters encounter hypothermia, snowstorms, exciting botanical discoveries, sabotage, and wildfire.

The book seamlessly weaves together the fictional stories of the characters and real natural history of Yellowstone National Park—or as they refer to it throughout the book since it was the only national park at that time, “the Nation’s Park.” One of my favorite passages is the discovery of a new plant, and Miss Bartram’s attempts at documenting it:

He then led me to a solitary pink blossom, growing next to the stream.

“Do you know what it is?” he asked.

I had to admit, even after close inspection under my hand lens, I could not name it. Located as it was next to a stream, with three sepals and three petals, a member of Orchidaceae was the best that I could do for certain.

“Joseph has asked me not to remove it,” Professor Merriam informed me.

I must have looked at him very strangely because he hastily continued.

“It is alone,” the Professor explained. “And since it cannot be named, Joseph is convinced that it must be sacred.”

Professor Merriam watched me closely for my reaction. Of course, that was the most ridiculous thing I had ever heard, and I told him so.

You cannot name it if you do not take it,” I reminded him. “Besides, what about the collection?”

…”It is a slipper of Venus,” Mr. Wylloe said to me….”Or a fairy slipper. I have heard it called different things associated with footwear on the rare occasions I have seen them near my cabin.”

…Of course, Mr. Wylloe’s information, like the term Indian paintbrush and all other such non-scientific nomenclature, gave me little if anything to go on. A fairy slipper could be anything from a Cypripedium to a Lilium to a Campanula.

I opened my journal and started to write a physical description but then hesitated, removing my colors from my case instead. Perhaps the process of observation and reflection needed to illustrate the specimen would help me come to better know it and, thus, identify it. At least that was my thinking.

Illustrating its precise form was relatively easy. The flower stood atop a small, sheathed stalk which barely held its own in a bed of decaying wood thick with moss. Once I pushed the debris out of the way, I could see that it also had a single basal leaf which was just beginning to emerge.

The flower itself was easy enough to capture on paper, its bilaterally symmetrical petals and prominent lip all easily translated for my visual record. It was not the flower’s form which gave me pause, but rather the color, a shocking pinkish purple with tiger-like stripes tinged along its edges with a golden brown….

I tried with my colors to capture the plant on paper, but after more than two hours, the day was drawing to a close and my attempts were either too bland, not at all capturing the showiness of the specimen, or too gilded, losing its sense of naturalness in my clumsy translations (88-89).

The fairy slipper, or calypso orchid, is a beautiful and delicate addition to early spring. Photo courtesy of Google images

The fairy slipper, or calypso orchid, is a beautiful and delicate addition to early spring. Photo courtesy of Google images

I found this book to have a land ethic, similar to the one Aldo Leopold discusses in A Sand County Almanac—the idea that humans are part of the greater biotic community rather than rulers over it. Much of this comes from the words of Professor Merriam and Miss Bartram, though rather than bringing a land ethic into the Park it develops throughout their time in the wilderness. There are also some minor characters who show a strong land ethic. In a letter to a good friend back home, Bartram writes:

Any additional incursions by the railroad, with their plans to dam the river and make right-of-ways for the railroad to haul both tourists and gold from a mine near the northern border of the Park, will compromise if not outright condemn the natural features of the Park for generations yet to come.

I, for one, am relieved. The sheer ruggedness of Park roadways keeps travel to a minimum, and forces those of us with a sincere desire to partake of the Park’s beauties and wonders to leave the wagons behind and travel on our own volition. It is only on foot that you can see, hear, smell, and touch the wonders that are all around us here. Otherwise, you miss too much. In fact, I would argue that you miss it all.

She also speaks about sitting and watching birds for hours and spending the whole day wandering the hillsides delighted by the sheer beauty of her surroundings.

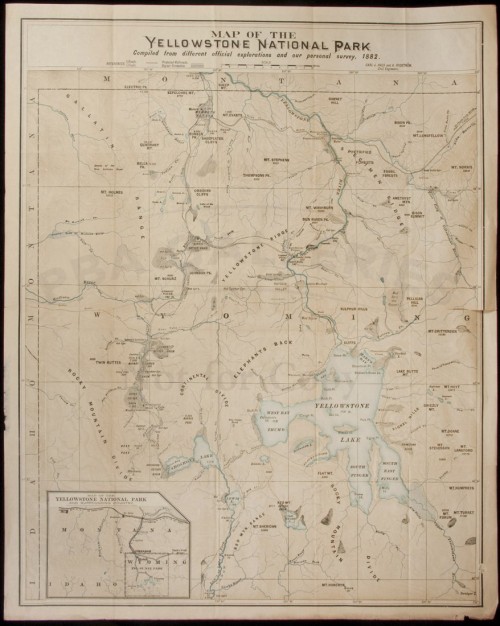

An 1882 map of Yellowstone National Park. Illustration courtesy of Google images

An 1882 map of Yellowstone National Park. Illustration courtesy of Google images

Diane Smith, when asked how her background in science and the environment helped inform her approach to writing the novel, said:

I think it’s important to point out that I have no training as a scientist. I believe all of us can, and should, develop a very basic understanding and appreciation of science and mathematics. At their heart, both are exquisitely simple and elegant if you can get past the scientific jargon.

I think that all too often we think of scientists or naturalists as people who know everything, who have extensive formal training, who are amazing artists. We forget that they had to start somewhere. And that they really probably don’t know everything. The root of both science and naturalizing is paying attention to the world around you and recording observations, whether it’s through drawing, photography, written lists, poetry, or any of the other infinite options.

While reading this book it never occurred to me that the author wasn’t trained in the sciences. This gives me hope. Hope for me in my journey as a naturalist and hope for other people who want to find that part of themselves.

Ryan Weisberg is a graduate student in North Cascades Institute and Western Washington University’s M.Ed. program. Ryan grew up here in Washington, exploring the natural areas around Bellingham and in the Cascades. Ryan is the Chattermarks editor this year during their residency at the North Cascades Environmental Learning Center.