Mason Bees and Honey Bees: What's the Difference?

By Kevin Sutton

There were some things I knew about bees when starting this project; what I didn’t know was exactly how much I didn’t know.

When someone says “bees”, I immediately think of the western honeybee (Apis mellifera). Maybe it’s because of the honey bee’s depiction in popular culture (see Honey Nut Cheerios) or maybe it’s because of the long relationship between humans and bees.

Humans have been trying to domesticate honey bees for thousands of years; evidence has been found in cave paintings in Spain, hieroglyphs in Egypt, on coins in Greece, and more and it makes sense; bees give us honey, wax, and all of our food through pollinating our crops.

The term wild bee is used for those species that don’t produce honey. There are 20,000 species of bee in the world, 4,000 native to North America, and 600 native to Washington alone. With such daunting numbers, I focused on one particular native bee, the orchard mason bee (Osmia lignaria).

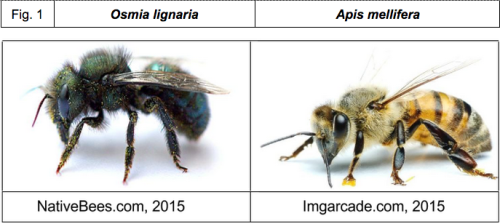

While similar to A. mellifera in size and shape, O. lignaria differs in coloring, some physical attributes (fig. 1), and most significantly, social structure:

| O. lignaria | A. mellifera |

| Metallic blue/green | Classic yellow and black striped |

| Nest in tubes, holes, hollow reeds, etc. | Builds a hive of wax |

| Solitary but will live near other mason bees | Social: lives in colonies up to 70,000 |

| Each female lays eggs | Only the queen lays eggs |

| Average range of 100 yards | Average range of two miles |

| 250 – 300 bees sufficient to pollinate 1 acre | one hive per acre (30,000 – 70,000 bees) |

| Gathers pollen by stuffing it between hairs on abdomen | Gathers pollen by storing it in specially adapted pockets on the rear legs |

| Stores pockets of pollen between larva | Turns pollen into honey and stores for winter |

| Eggs hatch in summer, larva hibernate through winter, emerge as bees in spring, repeat | Eggs regularly tended, hive comes together during winter (like penguins), become more active in spring |

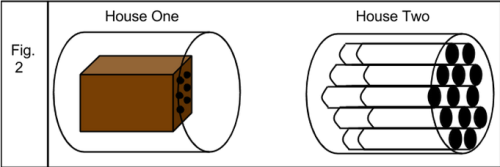

For my project, I wanted to see if there were mason bees at the North Cascades Institute. To do that, I constructed two mason bee houses and stashed them in a rock wall near my house. Each house is made of the same materials (wood for a base, support, and backing and a compressed cardboard tube for the shell) but the internal pieces, where the Mason Bees will hopefully nest, are different. The interior nesting holes in house one are made from commercially drilled slats of wood that have been taped together, while the nesting holes in house two are from pieces of bamboo I cut, dried, and tied together (fig. 2).

I put the houses outside on May 15, 2015 but as of this writing, June 12, 2015, there is no sign of use. My research said most mason bees are actively laying eggs in early April and with the unusually early and warm spring we’ve had, I expect the process began much earlier than that. Both houses will stay up until September when I transfer to Bellingham and if nothing else, will try again in March 2016 when I return to my house and garden in Portland, OR.