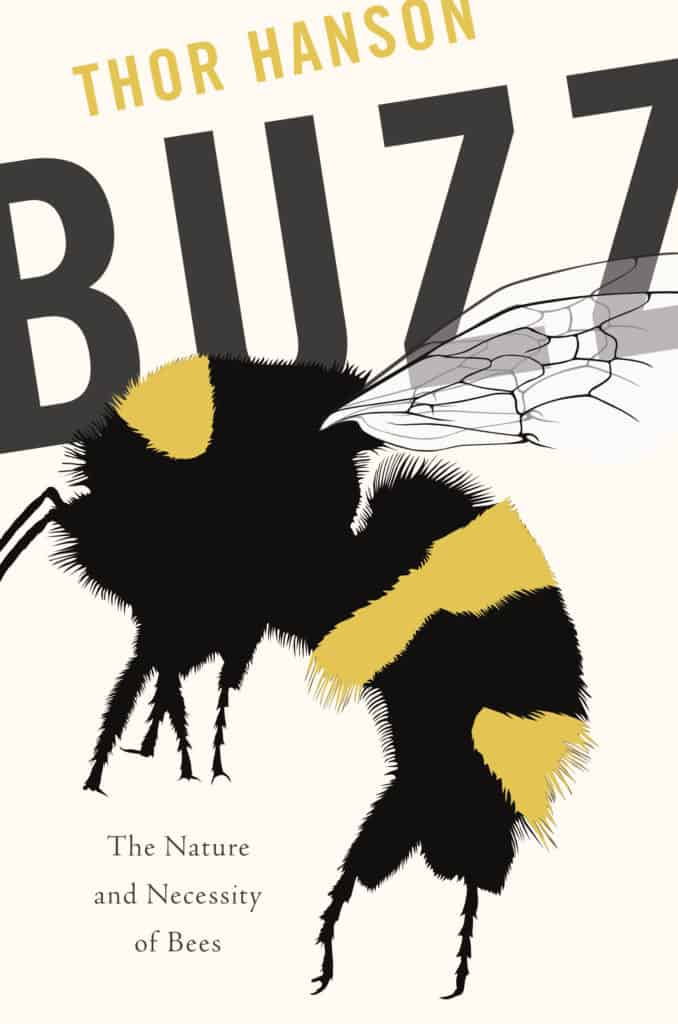

Buzz: The Nature and Necessity of Bees

The crossbow fired with a dull thwack and we watched its bolt disappear upward into the leaves and branches, trailing a length of monofilament fishing line that glinted in the scattered beams of sunlight. My field assistant looked up from the bow’s sight and nodded in satisfaction, feeding out more line from a spinning reel duct-taped to the front grip. For him, this was all in a day’s work, the standard procedure for helping biologists position ropes and research equipment high up in Costa Rica’s rainforest canopy. For me, it marked a turning point. Within minutes, a colleague and I had hoisted our insect trap into position, and for the first time in my career, I was officially studying bees. Or at least trying to.

The project didn’t exactly go as planned. Days of shooting arrows at trees and hauling up various contraptions produced only a handful of specimens, mostly from one exciting moment when a dangling trap inadvertently whacked a nest, and the whole hive attacked. The situation was infuriating – not only for all the wasted time and effort, but because I knew the bees were up there. I could see them clearly in the reams of genetic data I’d collected on the very trees where we were setting our traps. By comparing the DNA from adults to that of their seeds, I knew that pollen was moving around all over the place – not just among neighboring trees, but between individuals nearly a mile and a half (2.3 kilometers) apart. And because those trees belonged to the pea family, I knew that their clusters of purple flowers were designed for bee pollination, just like the vetches, clovers, sweet peas, and other common varieties back home. In the end, I had to admit defeat, but the experience sparked a fascination that wouldn’t rest. I immediately sought out courses on the taxonomy and behavior of bees, and have looked for ways to chase after them – in my work and in daily life – ever since. Sometimes I even catch a few.

Like anyone interested in bees, I’ve followed recent trends with an increasing sense of worry. Since beekeepers first reported signs of “Colony Collapse Disorder” in 2006, millions of domestic honeybee hives have simply winked out. Investigators point to a variety of causes, from pesticides to parasites, and have also uncovered steep declines in many wild species. With news reports, documentaries, and even a Presidential Task Force ringing the alarm bells, public awareness of the situation has perhaps never been higher. But what do we really know of bees? Even experts often stumble over the details. Once, while listening to the radio in my car, I heard a noted historian of science describing how early colonists arriving at Jamestown and Plymouth brought honeybees with them from Europe. If they hadn’t, he explained, there would have been nothing to pollinate their crops. I nearly drove off the road! What about the 4,000 species of native bees already buzzing happily around North America? But that’s not the worst of it. On the bookshelf in my office, I keep a hardbound copy of the volume Bees of the World. It was written by well-regarded entomologists and published by a good non-fiction press, and the cover features a lovely close-up photograph . . . of a fly.

It’s often said that bees provide every third bite of food in the human diet, but like so many of the natural wonders we rely on, they now fly mostly under the radar. In 1912, British entomologist Frederick William Sladen observed, “Everyone knows the burly, good-natured bumble-bee.” That may have been true in the English countryside of Sladen’s day, but a century later we find ourselves more familiar with the plight of bees than with the bees themselves. Luckily for all of us, reconnecting with bees can be as easy as walking out your front door on a summer day, wherever you happen to live. Filter out the commotion of modern life and you can still hear them buzzing – those ubiquitous but overlooked visitors to every patch of open ground, from orchards, farms, and forests to city parks, vacant lots, highway medians, and backyard gardens. It’s also lucky that what we do know about bees makes for an irresistible story. It begins with ancient specimens trapped in amber and soon moves on to honey-loving birds, the origin of flowers, mimicry, cuckoos, scent plumes, impossible aerodynamics, and, quite possibly, a major step in our own evolution. Exploring the history and biology of these essential creatures can transform anyone into an enthusiast, and, just as importantly, make you want to go straight outside on the next sunny day, find a bee on a flower, and settle down to watch.

Catch Hanson reading from Buzz at an upcoming reading:

Paulina Springs Books

Thursday, August 2, 2018

6:30 p.m.

252 W Hood Ave

Sisters, OR

Mrs. Dalloway’s Bookstore

Friday, August 3, 2018

7:30 p.m.

2904 College Avenue

Berkeley, CA

San Francisco Botanical Garden

co-sponsored by Green Apple Books

Saturday, August 4, 2018

3:00 p.m.

1199 9th Ave

San Francisco, CA

Heidrun Meadery

co-sponsored by Point Reyes Books

Sunday, August 5, 2018

3:00 p.m.

11925 CA-1

Point Reyes Station, CA

Lopez Bookshop

Friday, August 24, 2018

7:00 p.m.

211 Lopez Road, Plaza Building

Lopez Island, WA

Books A’Sail – Literary Cruise on Schooner Zodiac

September 11-13, 2018

San Juan Islands, WA

Town Hall Seattle

Wednesday, September 26, 2018

7:30 p.m.

event to be held at The Summit Event Space

420 East Pike St.

Settle, WA

Jefferson County Library

Huntingford Humanities Lecture

Thursday, September 27, 2018

6:30 p.m.

event to be held at Chimicum High School Auditorium

91 W Valley Rd

Chimacum, WA

Pacific Northwest Booksellers Association

Saturday, September 29, 2018

Breakfast with the Authors

Hotel Murano

Tacoma, WA

Adapted from Buzz: The Nature and Necessity of Bees. Copyright © 2018 by Thor Hanson. Available from Basic Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, a division of PBG Publishing, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc.