Listening to Coyote

By Emily Ford, part of the Institute’s 15th Graduate Cohort.

After a rainy and dark winter, I’ve started to recognize the North Cascades as I remember them when I arrived last summer. Pyramid Mountain’s East wing is shaking off the snow, reminding me of summer as if it were an old friend. Soon again, Pyramid will be the snowless, chiseled, gray spire that taunted my stout climbing heart, and proved to me that its summit remains sacred beyond tired muscles, novice skills and terminal daylight. It is no longer capped by cornices like ice cream cone swirls that soften its thrust into the clouds. Pyramid stands out along the Diablo Lake skyline once more, and reminds me how deeply at home I have become.

Ok I got a little carried away. This blog is not about the North Cascades. In fact, I desperately needed to leave. I needed to go back to the desert, where I’ve returned to backpack and guide river trips for many years. When water has been scorned in the Northwest for being too much, the water in the desert is praised – and as Edward Abbey notes – exactly the right amount. Which is hilarious because it was 90 degrees in Seattle, but it rained every day, and even hailed, during my spring break trip in the Canyonlands.

Eating dinner in a slickrock alcove, I watched a storm approach at sunset. Shadows danced among the spires creating quite the dinner theater.

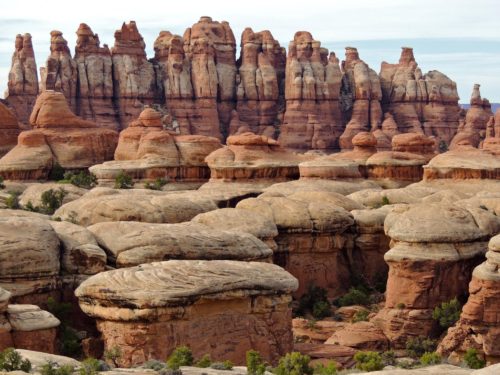

Although I prefer company on my outdoor adventures, logistics and preferences don’t often line up. So I headed into the backcountry on my own, which makes for a different kind of trip entirely. And the trip I had planned was no cake walk (although I did bring Snickers Bars and Good n’ Plenties). I started in the Needles, and spent two nights among tall spires known as hoodoos and deep canyons called grabens.

Canyonlands National Park’s three sections. Moab is near the Northeast corner. Dotted line is my trip, from East to West, and back again

The Needles from above Elephant Canyon. I wish I was underwater, swimming through the giant stone lily pads and tall reeds

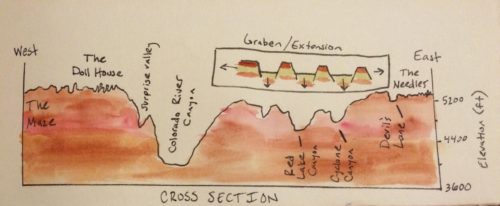

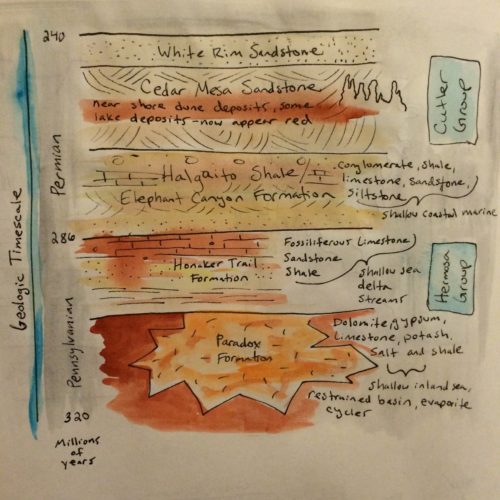

The picturesque needles are whittled by erosion out of the 260 million year old Cedar Mesa Sandstone. It is the horizontal layer of rock that rested at the highest elevation of my journey, formed by seaside dune deposits. The lowest layer, about 1000 feet down, was formed 320 million years ago, when the Utah desert was under a shallow salt water seaway. It would periodically dry up and refill, leaving salt and other evaporites. This created the Paradox Formation, an unstably less dense mass of material that is responsible for the warping, tilting, and stretching of this area to create grabens. Grabens are long, straight cracks that look like stretch marks on the surface. Hike parallel to them, and they’re your best friend. Hike perpendicular to them, and they can be a nightmare.

hair-extensions-me |

hair-extensions-don |

hair extensions clip in

brazilian-hair-on |

brazilian-hair-on |

besthairbuy-wigs |

everafterguide-human-hair-wigs |

jet black hair

lace-front-wigs |

omywigs |

Full Lace Wigs ,

clip in human hair extensions

hair extensions for short hair

Above Cyclone Canyon graben, appropriately named for its high winds. Down, across, and up the other side.

Cross section of most of my trip, beginning in The Needles. Above is a geologic explanation of how the three parallel canyons, and many more, were formed through the process of extension

I made my way up and over each graben (Devil’s Lane, Cyclone Canyon, Red Lake Canyon) like giant pages of stone, and finally down to the Colorado River. This allowed me to hike through 60 million years of time, captured in the layered stratigraphy between the Cedar Mesa Sandstone and the Paradox Formation. Along the way, day hikers gave me quizzical looks when they saw two yellow oars sticking out of my backpack like the wings on Hermes’ head. Many asked if I was alone. After a while, there were no other people. But solitude in the desert is just as vibrant as a crowded room. Coyote, Rattlesnake, Canyon Wren, Sage, wildflowers, even the wind, fickle sky and slippery mud were lively company.

Stuck between a Rattlesnake and a hard place, also known as a cliff. I was able to climb down and around, giving this Prairie Rattlesnake plenty of space, but capturing this picture with a high zoom lens

A stratigraphic column illustrates the layers of rock, their age, their composition and the environment in which they formed.

I blew up my packraft a mile upriver, taking light-headed breaks to filter muddy water. Most packrafts are expensive, and rightfully so for their light-but-sturdy design. But as a broke graduate student with river guiding experience, I figured a twenty dollar children’s inflatable raft would do the trick. I had a leisurely crossing, with a grain of salt. (Or rather, the entire Paradox Formation beneath me) Around the next meander, I could hear rapids, the first in a series of infamous whitewater through Cataract Canyon. Once across, I wrestled the air out of my slippery, muddy vessel and left it behind a rock. Although I was no longer carrying my boat, I had five heavy Liters of water for the next two and a half days in some of the most remote terrain in the country. And it all started with walking back up to the Cedar Mesa Sandstone.

The Doll House on the West mesa high above the Colorado River

Since there were no trails on the map, I followed washes, old game trails and the occasional rock cairn into The Fins. Although I was venturing into a trail-less country known as “The Maze,” near where the well-known nightmare “127 hours” took place, cairns gave me hope that my idea wasn’t so crazy after all. The intricate wiggles of The Fins canyons on my topography map had finally enticed me here. I tracked Coyote and Coyote’s pup by their footprints in the sand and stopped to look at many scats full of Juniper berries, Pinyon Pine seeds, fur and small bones. The quality and urgency of the birds’ chattering was easy to listen to for clues about what else might be going on beyond my sight. They are wonderful messengers of the mesa, but everyone already knew of my presence as my heavy hiking boots clumsily made their way through the sand.

Knapped by ancient hands, this is one of many lithics I found in washes. It is important to leave these cultural artifacts within their local landscape

As I ate my lunch, a Golden Eagle flew in, but quickly flew out and over the ridge

Wondering if I had passed my turn into the canyon, I motioned to get the map out of my backpack. That second, a coyote barked three times and finished with a howl. I went rigid and chills ran up my spine as it echoed up the towering canyons to the North. I waited, smiling, and it barked and howled once more. Over the last few weeks, I’ve been studying the Native stories of Coyote’s trickery. I’ve also been teaching from Coyote’s Guide to Mentoring which helps facilitators nudge students towards experiencing nature in more depth. For example, rewilding philosophies and activities engage the senses and emotions and follow natural learning cycles. Such learning can be daunting, but deeply satisfying and transformative. A mentor, much like Coyote, is always on the periphery, ready to offer encouragement, a new spontaneous challenge, or another point of view. This teaching pedagogy focuses on the dynamic nature of comfort zones, all while seeking groundedness in self, community and the environment.

I never saw the Coyote that I followed and heard in the Maze. But I did see this Coyote on the first morning of my Spring Break trip, after I slept out in Idaho’s high desert on my way down to Utah. I caught the fleeting glimpse of Coyote’s white face while driving back to the highway, and got out of my car to share this moment

The following is a selection from Terry Tempest Williams’ Red: Passion and Patience in the Desert. A testament to the honesty of redrock country, these words were prophetically accurate to my own experience in The Canyonlands.

This is Coyote’s country – a landscape of the imagination, where nothing is as it appears. The buttes, mesas and redrock spires beckon you to see them as something other: a cathedral, a tabletop, bear’s ears or nuns. Windows and arches ask you to recall what is no longer there, to taste the wind for the sandstone it carries… Just when you believe in your own sense of place, plan on getting lost. It’s not your fault – blame it on Coyote… This is bedrock of southern Utah’s beauty: its chameleon nature according to light and weather and season encourages us to make peace with our own contradictory nature. The trickster quality of the canyons in Coyote’s cachet… Coyote knows we do not matter. He is an ally because he cares enough to stay wary. He teaches us how to survive. Coyote’s howl above the canyon says the desert may not depend on his life, but his life depends on the desert. We would do well to listen. -Williams, 24-25

Her words not only reflect my hiking experience but also my practice as a student and a teacher at North Cascades Institute. We have many new challenges facing us and our planet and we must find new ways to solve problems. We must practice and teach critical thinking and cultivate compassion. Being active, outside, involved in our communities and aware of our surroundings profoundly affects our mental and physical health. It is also what nurtures our soul, our understanding and experience of being human.

We would do well to listen to Coyote.