Ana Maria Spagna's "Reclaimers"

Guest post by Ana Maria Spagna; an excerpt from the Prologue “The Low Ground” to Reclaimers, (UW Press 2015)

Spagna reads from her new book at Village Books in Bellingham on Thursday, October 8, at 7 pm as part of our Nature of Writing Fall Speaker Series; free!

When I started telling friends about my interest in reclamation, everyone had a story. Did I know about High Line Park in New York City on a reclaimed elevated freight rail? How about Seattle’s plan to reclaim wasted heat from data centers, the so-called Cloud, to power nearby neighborhoods? Reclaiming appeared everywhere, out of nowhere; it seemed to be, in some ways, the backdrop of our time. Nearly every major American city has a re-store where would-be remodelers can buy lumber and hardware salvaged from demolished buildings. Most watersheds have seen restoration, and some—the Hudson, the Cuyahoga—have been nothing short of miraculous. Even small-scale dam removal, it turns out, was nothing new. The nonprofit river advocacy group American Rivers estimates that in the past century 925 dams have been removed from rivers.

Then there were Native Americans. If reclamation—at least the way it interested me—had to do with land and water, the original inhabitants were the ones with the most at stake. For the past fifty years, I’d learn, all across the country Indian tribes have been taking back what’s been stolen from them: the Taos Pueblo in New Mexico, the Menominee in Wisconsin, the Passamaquoddy in Maine, the Colville in Washington.

At the beginning, I didn’t know any of this. I wouldn’t until I left home.

So I did. I took a long solo trip—or more precisely a series of them—spurred by curiosity and hemmed by my own geography and finances. Over three years, I’d yo-yo up and down the west edge of the continent on either side of the long strip of mountains—Panamints, Sierras, Cascades—that have defined my adult life and alongside rivers that have, in literal ways, sustained me—the Feather, the Columbia, the Stehekin—in an aging Buick along a zigzagging dot-to-dot route that loosely connects where I grew up in a desert suburb of Los Angeles to where I’ve landed in the North Cascades. I’d walk over sand dunes past lime green mesquite and follow game trails among dormant oaks, watch steelhead through glass and befriend a single red fox. I’d talk to elders and activists, bureaucrats and lawyers and small town mechanics. I’d tell everyone my three part theory of reclaiming, and if their eyes occasionally glazed over at “taking back” and “making right”—weary perhaps of the eternal moral tug-of-war—by the time I got to “make useful” they had some things to say. And I tried to listen.

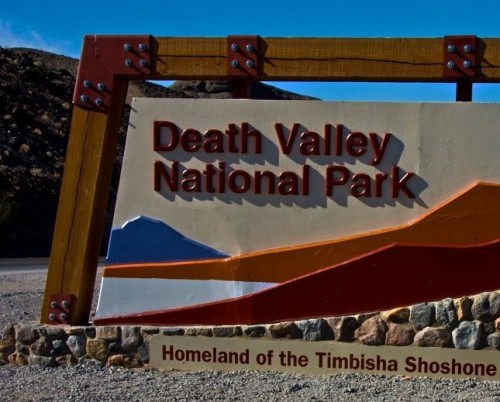

The sign approaching Death Valley that names it “Homeland of the Timbisha Shoshone”

By chance and later with intention, I found myself immersed in the sagas of two small California tribes with big goals: the Timbisha Shoshone who reclaimed their ancestral land in Furnace Creek in the center of Death Valley National Park more than a decade ago, and the Mountain Maidu, a federally unrecognized tribe in the Northern Sierras, who aimed to reclaim a sacred valley from a multinational utility company and planned to manage it using traditional ecological knowledge.

On the surface, these stories caught my attention because they dovetailed with my own experiences in Stehekin: the Timbisha had difficult dealings with the National Park Service, the Maidu worked their forested lands with chainsaws and pruners—planting, thinning, harvesting—and held frequent community potlucks, much as we did. But there were deeper reasons as well. I’d written a book about my father’s involvement in the early civil rights movement, and the heroes and she-roes I met doing the research, the everyday people who stood up to make a difference, had impressed me. I admired their courage, their fortitude, their unwavering faith. But like the Catholic faith of my childhood, their core beliefs lacked a deep connection with the earth: land, air, water, non-humans. That unspoken connection defined me. It bound me to Laurie. We’d met in the woods and still two decades later spend all our best time together outdoors: hiking dusty switchbacks through beetle-kill firs, skiing by the silent frozen river, tending our friends’ neglected gardens, one after the next, in their absence. And it bound me to my neighbors, transcending even our most rancorous battles. Mid-winter nearly every conversation in the post office centers on how many trumpeter swans have returned to the lake. (Thirty-seven one day, forty-three the next; everyone keeps count.) I claimed often that my interest in reclamation stemmed from intellectual curiosity, and joked half-earnestly that I mostly needed to get away from home—to think about any place else, to write about any place else—but underneath, always, lay something more. I wanted to explore that connection. I wanted to tell stories about people who try, in plain and practical ways, to take nature back, make it right, and make it useful. Even when ideas about how to do so shift infuriatingly.

Me with Maidu elder Beverly Ogle at the celebration of their reclamation of Humbug Valley from PG&E