In the Era of Fire Lookouts: Fire Suppression in the North Cascades

By Adam Bates, graduate student in the Institute’s 15th cohort.

Fire lookouts have captured the imagination of the American public for over seventy-five years. The notion that one could spend a summer atop a mountain in solitude and seclusion holds a certain romanticism that was perpetuated by numerous authors, poets, artists and backcountry enthusiasts. Therein lies my interest in and affinity for fire lookouts, the romance and challenge of mountaintop hermitage.

Retired National Park Service employee Gerry Cook spent three summers as a lookout, using his earnings to entirely pay his through his undergraduate degree at Washington State University. “You can revel in your time there (on lookout) for the rest of your life,” says Cook. “It’s romanticized in everyone’s imagination. So, once you’re done, you can go right into that fantasy world and live there forever.”

By the 1930’s, vast systems of fire lookouts were being constructed around Washington State. Over four hundred lookouts were built and manned over the coming decades, although many were soon found to be ineffective at spotting fire from their vantage points. The harsh winters in higher elevations wreaked havoc on the structures themselves, making them cost prohibitive to maintain.

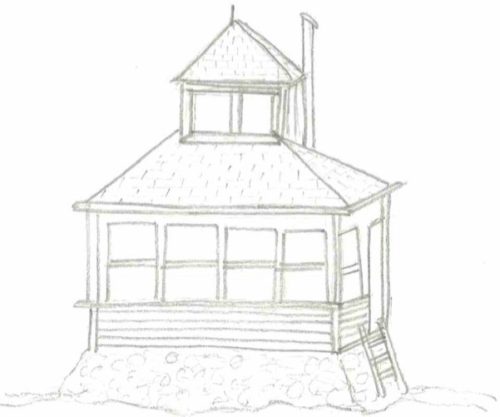

Sketch by Adam Bates of a D-6 Cupola, the first standardized lookout style by the US Forest Service. It debuted in 1915 atop Mt. Hood, named after the USFS District where it first appeared, District-6.

Large swathes of land were being designated as forest reserves through executive order by late in the 19th century. President Grover Cleveland set aside a total of 21 million acres in 1893, including the Pacific Forest Reserve across much of Washington State, which had been granted statehood in 1889. Without the benefit of aircraft surveillance, transistor radios, heat systems, or a road system in wild lands, lookouts became the first line of defense for spotting fires and protecting public lands from large-scale wildfires. Miles upon miles of telephone wires were strung between lookouts in order to communicate the location of fires and the needs of those stationed as lookouts.

By the end of World War II, improvements in aircraft surveillance and radio communications were the end of an era for fire lookouts. As lookout stations became obsolete, they were decommissioned by whatever means necessary. Logging roads and highways were penetrating deeper and deeper into wilderness areas, making many lookouts more easily accessible.

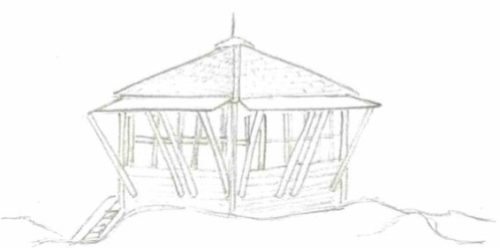

Sketch by Adam Bates of a L-4 groundhouse. Characteristic of the 1930s, this model has either a hipped or standard roof and a catwalk around if elevated. Notable lookouts of this style include Sourdough Mountain, Desolation Peak, and Copper Mountain.

Constructing a network of fire lookouts allowed those working as lookouts to pinpoint the location of a fire from their own mountaintop, while another lookout did the same. They were then able to triangulate and corroborate the exact location of any fires that were spotted. Many lookouts in North Cascades National Park and the surrounding Forest Service lands have been decommissioned and some dismantled. Those that remain are listed on the National Historic Lookout Register, and some on the National Register of Historic Places. They remain as living history for the general public and can be still used in times of emergency or intense fire seasons.

Sketch by Adam Bates of a R-6 Flat Roof lookout. Typically elevated on stilts with a catwalk around the exterior with a flat roof, dimensions and height vary depending on location.

For over a century, wildfires and fire on any landscape has been viewed as destructive, dangerous, and unnecessary. For much of this time, it has been the official policy of the U.S. Forest Service that all backcountry and wild fires should be contained immediately. If this were not possible, plans should be made and set in motion to obtain complete control before ten o’clock the following morning. The 10 a.m. policy was officially adopted by the 1930’s with the overabundance of manpower and money available through the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) and other such New Deal programs. The CCC was succeeded by smokejumpers, the first of which began operational testing in 1939 on the Chelan National Forest and was widely adopted in Washington State after World War II. By 1970 there was a great deal of information and research being done on the positive effects of fire ecology, which allowed the Forest Service to move away from total fire suppression.

Ultimately, the damage has already been done. By removing regular fire of mixed severity from a landscape, vegetation fuels that sustain fires have accumulated to unprecedented levels. There are catastrophic fires occurring with surprising frequency in recent years, the costs and effects of which are amplifying. To suggest that fire is always a good thing, especially when people’s lives and homes are at stake, would be glib and inappropriate. This project and my interest in fire lookouts and research of their history has led me to the much broader question and topic of fire and forest ecology, which involves both ethical and practical questions. A complex and polarizing topic about the place of wildfire in our lives as we struggle to cope with the effects of catastrophic fire seasons in the North Cascades and beyond.

For a deeper experience into firelookouts, check out Adam’s Audio Presentation on Fire Lookouts.

Audio Player

Music by Adam Bates. Readings by Emily Ford, Adam Bates, Aly Gourd, Joe Loviska, and Marcus Something of the words of Jack Kerouac, Edward Abbey and Gary Snyder. “Smokey the Bear” was written by Steve Nelson and Jack Rollins, performed by Eddy Arnold for a 1952 public service announcement.