The Long View: Geology, John McPhee and me

Graduate student Jacob Belsher writes a natural history book review on John McPhee’s Basin and Range

Graduate student Jacob Belsher writes a natural history book review on John McPhee’s Basin and Range

According to James Hutton, a Scottish geologist working in the late 18th century:

“To a naturalist nothing is indifferent; the humble moss that creeps upon the stone is equally interesting as the lofty pine which so beautifully adorns the valley or the mountain: but to a naturalist who is reading in the face of the rocks the annuals of a former world, the mossy covering which obstructs his view and renders undistinguishable the different species of stone, is no less than a serious subject of regret.”

Entertainment value aside, Hutton’s remark may be of some use in inspiring a more informed perspective of how our biotic lives play out upon the earth’s abiotic bedrock. An understanding of the primary geological forces shaping our planet helps elaborate this perspective, and writer John McPhee rises to the task in his first in a series of books on the geology of North American landscapes: Basin and Range. This largely accessible book focuses specifically on the physiographic province of the United States ranging from eastern California to eastern Utah.

The rigid, outer most shell of our rocky planet is called the lithosphere. All life, from Hutton’s “green slime” to the suspended inhabitants of the marine world, act out their roles on this stage. It turns out that these roles are all minor ones.

The actors remain on stage and deliver their few lines and are gone so quickly that it was not until the late 1950s and early 60s that some scientists noticed the stage was moving. The current widely accepted theory that describes this motion is called Plate tectonics.

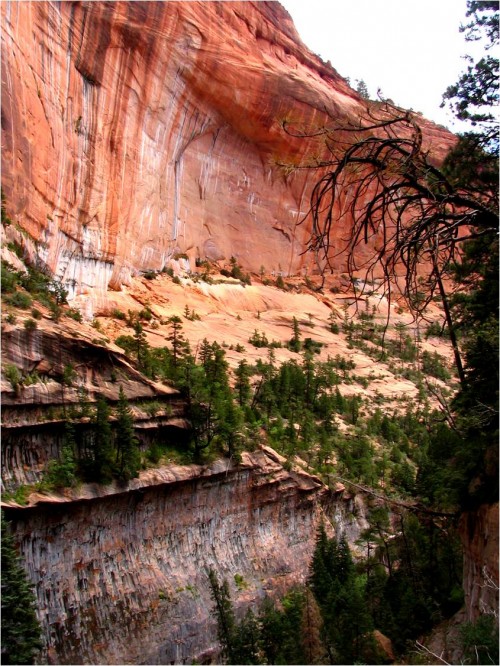

A broader view of rising canyon walls of Zion National Park.

A broader view of rising canyon walls of Zion National Park.

Plate tectonics, often mistakenly equated with Continental Drift Theory, holds that earth’s lithosphere is (currently) divided into approximately 15 plates, ranging in size from the very large Pacific and Eurasian plates, to our own tiny Juan de Fuca plate. These 100-200km thick plates “float” upon the relatively highly viscous and ductile (but solid) asthenosphere. Over time, driven perhaps by giant convective cells operating in the earth’s mantle, differences in density between the asthenosphere and lithosphere, and the gravitational pull of the sun and moon, these plates move around. A new plate is formed on the lower surfaces of the lithosphere where two plates diverge, creating an oceanic ridge where molten rock finds its way up from the mantle and “seafloor spreading” occurs. Old pieces of plate are recycled back into molten form where plates meet; here, old seafloor may be driven beneath a neighboring plate and back down into the asthenosphere, forming our deepest ocean trenches along the way. Thus, the entire ocean floor is periodically swept clean, recycled and renewed every three to four hundred million years. This explains why today we find only “young” rocks on the seafloor, as well as relatively shallow sediment deposition.

Above two photos depict the amazing variance of coastal and inland mountains due to plate tectonics. Leading photo of sandstone and lava flow deposits outside of St. George, Utah. Second photo of the familiar beauty of the North Cascades Range in Washington.

Above two photos depict the amazing variance of coastal and inland mountains due to plate tectonics. Leading photo of sandstone and lava flow deposits outside of St. George, Utah. Second photo of the familiar beauty of the North Cascades Range in Washington.

The much smaller un-inundated portions of the globe are the less dense (not compressed by the weight of the ocean) parts of the lithosphere familiar to us as continents. The largest mountain ranges adorning these insubstantial parts of our earth, from the perspective of Plate tectonics, arise in two ways. In one situation, newly melted seafloor is subducted beneath a neighboring continental plate to form volcanic mountains, as is the case with our own Cascades and the Andes of Peru and Chile. In the second case, a collision of two continents, independent of a deep ocean trench, results in the extinction of the shallow sea once separating the two landmasses as the plates crash together. This is the case with the still rising Himalayan Mountains, and with our much older Rockies. Though the rock of terra firma, floating high and dry, may persist much longer than its marine counterparts (billions of years, sometimes) it doesn’t escape the same inevitable cycle; it simply must wait a bit longer to be ground down by wind and rain and ice and washed to the sea. The stage is truly moving beneath our feet, in some places as fast as fingernails grow.

The picture drawn by Plate tectonics and so confidently discussed by John McPhee, helps us understand why, today, we find the fossilized remains of extinct sea creatures in the limestone summit of Everest. It also gives the lie to the precursory theory of Continental drift which failed to explain how continents might be plowing through the mistakenly assumed-to-be stationary seafloor.

The deep reds and browns that classically portray the unique geology of Zion National Park, Utah.

The deep reds and browns that classically portray the unique geology of Zion National Park, Utah.

This perspective of extra-human time, typified in this case by the realization that the surface of the earth is in motion and being acted on by forces of unimaginable scope and endurance has proven to be somewhat of a theme in the natural history writings I have been perusing. The authors Diamond, Gould, and now McPhee all tell stories that span extremely long time frames: that of human history, to that of the history of life, and now to the history of the planet itself. Considering these epic slices of time, for me, causes a sensation that is oddly chilling and comforting, simultaneously.

The sensation of being dwarfed by history and the forces of nature is what I think will stick with me, if nothing else, from my natural history as a graduate student in North Cascades Institute’s Graduate M.Ed. Program. We are profoundly mistaken when we suppose ourselves as a species or as individuals to be somehow significant, to figure prominently in creation or what-have-you. All we have discovered about the nature of our world and our own existence says otherwise; the hot piece of rock we wander upon is spinning around an insignificant star in an endless sea of other stars. What we take as the permanent, solid ground beneath our feet is the melted vestige of a former world. The bodies we get around in are recent and untested models in an ancient lineage. Our society is likewise a new and untested one. Though it is hard to see, the lives we live and the world order we take for granted is fragile and by no means a sure thing. Of course, McPhee sums it up nicely for us as he writes:

“Geologists, dealing always with deep time, find that it seeps into their beings and affects them in various ways. They see the unbelievable swiftness with which one evolving species on the earth has learned to reach into the dirt of some tropical island and fling 747s into the sky. They see the thin band in which are the all but indiscernible stratifications of Cro-Magnon, Moses, Leonardo and now. Seeing a race unaware of its own instantaneousness in time, they can reel off all the species that have come and gone, with emphasis on those that have specialized themselves to death.”

Leading photo of Red Rocks outside of Las Vegas, Nevada. All photos courtesy of the author during his time spent living, exploring, and climbing the vast geologic landforms to be found in Utah, Nevada, and Washington.

Jacob, great review. Well written and the photos are outstanding. Thanks.