Watch your nose: Understanding White-Nose Syndrome and the Bats of the North Cascades National Park, part 2

Photo taken by Alan Hicks. Retrieved from batcon.org

This is part two of my series on bats. You can find part one here.

On March 11, hikers found the sick bat about 30 miles east of Seattle near North Bend, and took it to Progressive Animal Welfare Society (PAWS) for care. The bat died two days later, and had visible symptoms of a skin infection common in bats with White Nose Syndrome. -U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service.

Now that we know which bats live in the park and their ecological significance, we can dive into white-nose syndrome.

What is white-nose syndrome?

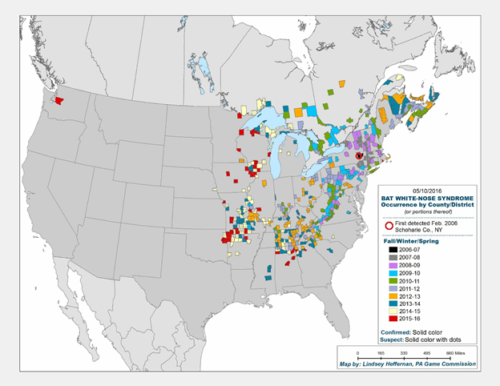

The first case of white-nose syndrome (WNS) in the U.S. occurred in February, 2006 in Albany, New York. Researchers documented a white substance around the muzzles, ears, and wings on both alive and dead bats in the Howes Cave. Upon further investigation it was discovered that the substance was a fungal growth of Pseudogymnoascus destructans (formerly Geomyces destructans). The fungus colonizes best on thinner outer tissue of bats (nose, ears, wings), eroding the skin and thriving off of inner-connective tissue. To date, it is thought that over six million bats have died to the syndrome in North America.

While the exact cause of death is uncertain, scientists hypothesize that the fungal growth disrupts their hibernating habits. Deceased bats with the syndrome have been reported with having significantly lower body weight compared to the population average at that time of year. When bats hibernate in cool, damp places over the winter P. destructans infects the bats. Whether awake or asleep, this added stress causes bats to use fat storage at a faster rate than normal. If a bat wakes up it will most likely not be able to find a food source at that time of year and die of starvation.

Map of counties with confirmed cases of White Nose Syndrome in Bats (May 10th, 2016). Retrieved from https://www.whitenosesyndrome.org/resources/map

WNS is not exclusive to North America. P. destructans is found widespread over Eurasia, causing bats of the region to also have the characteristic “white muzzle.” Eurasian bats, however, are not dying from the syndrome. Just like diseases caused mass extinctions of native populations in humans during European conquest, Eurasian bats have co-evolved with the fungus and therefore are not dying out. North American species, just being introduced to it this century, have not developed a resistance and are dying in mass.

Since 2006, the syndrome has been slowly spreading west, south, and even north into Canada. Taking a decade to reach a third of the way across the country, scientists on the west coast were preparing for the disease, expecting it to come before 2030. On March 11, 2016 in the Cascade Mountain range hikers found a dying little brown bat (M. lucifugus) on the trail and took it to an animal shelter for help. After two weeks of tests it was discovered to have the presence of P. destructans. On March 31, 2016 the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service informed the public about the first confirmed case on WNS in any western state.

What is being done about it?

The severity of WNS has caused states, federal agencies, universities, and non-profit organizations to combine resources continent wide. US Fish & Wildlife is the main stakeholder, creating a seven-part plan to organize all partners. Each team responsible for one part of the plan is critical to understanding and managing this national epidemic.

- Communication and Outreach: The first step towards a solution is education. This team is responsible for sharing resources and results with partners and the public. Through a dedicated communications and outreach team, new information and best practices involving management and education can be spread like never before.

- Data and Technical Information Management: Data management can be as unruly as fungal diseases without a dedicated team. Responsible for synthesizing and tracking data, this team updates a database so that partners nation wide can see progress in clear ways.

- Diagnostics: Part of that data collected is fully dedicated to consistent updates of the disease. This team is responsible for creating standards that researchers will use to monitor the fungus. Always updating with best methods, they will adapt to see what management practices are working.

- Disease Management: The fungus P. destructans could easily be killed with fungicide. However, such extreme measures could in turn harm more bats and the surrounding ecosystem. This team is responsible for finding ecologically sound methods of containment and removal without causing more ecological harm.

- Etiology, Epidemiological, and Ecological Research: Over the past decade research has been a cornerstone for finding patterns and breakthroughs to WNS. Responsible for research of both bats and P. destructans, this team provides raw data that can be transferred into the field.

- Disease Surveillance: Working on the ground, this team is responsible for collecting data on what the disease is doing. Early detection, like what was found in Washington State, is critical to responding as fast as possible.

- Conservation and Recovery (of Affected Bat Species): With such a large stressor, bats more than ever need large conservation efforts to have any chance of success. This group creates and implements conservation protocols so that no additional stressors are being placed on bat populations.

Photo retrieved from whitenosesyndrome.org

Can I help?

Absolutely! While the US Fish & Wildlife plan for dealing with WNS is massive, the public body needs to participate in conservation efforts to achieve best results. Many factors such as lack of knowledge and financial resources could initially alienate the public from such efforts. However, most public participation can be extremely beneficial with even the smallest amount of education, conservation, and construction.

- Education: Humanity has created many misconceptions about bats over the centuries. The majority of the public does not have an opinion on bats at best and view them as a pest at worst. With just one resource or two, most of those misconceptions can be transformed into correct knowledge about these amazing creatures. Either through workshops, festivals, or even online research, the public has more access than ever to reliable information on bats.

- Conservation: Along with education, there are multiple conservation efforts that the majority of the public can be involved with. First, the public should not disturb habitat. Most natural hibernacula are either blocked off with signs or so remote that public access is impossible. If anyone finds bats resting they should immediately leave as to not put more stress on the bats. After walking through any hibernacula it is important to immediately bleach all equipment as to avoid accidental spread of WNS. Second, the public should report anything unusual. If a bat is walking outside during winter, or if any bat is found dead on the trail, it should be reported immediately to the nearest authorities so that action can happen as soon as possible. Third, volunteer! There are plenty of opportunities to help organizations with data collection and conservation management. This is a great way to gain exposure to bats in the safest way possible.

- Construction: Interaction with local bat species does not end when leaving the park. In every neighborhood there is a possible bat population that needs as much help. Constructing bat-boxes is a cheap method for providing habitat for bats, even in sub-urban areas. Most bat-boxes can be constructed for less than $30.

If you want to keep up to date on all things WNS, check out whitenosesyndrome.org. It is the go to resource on the spread and prevention on this disease.