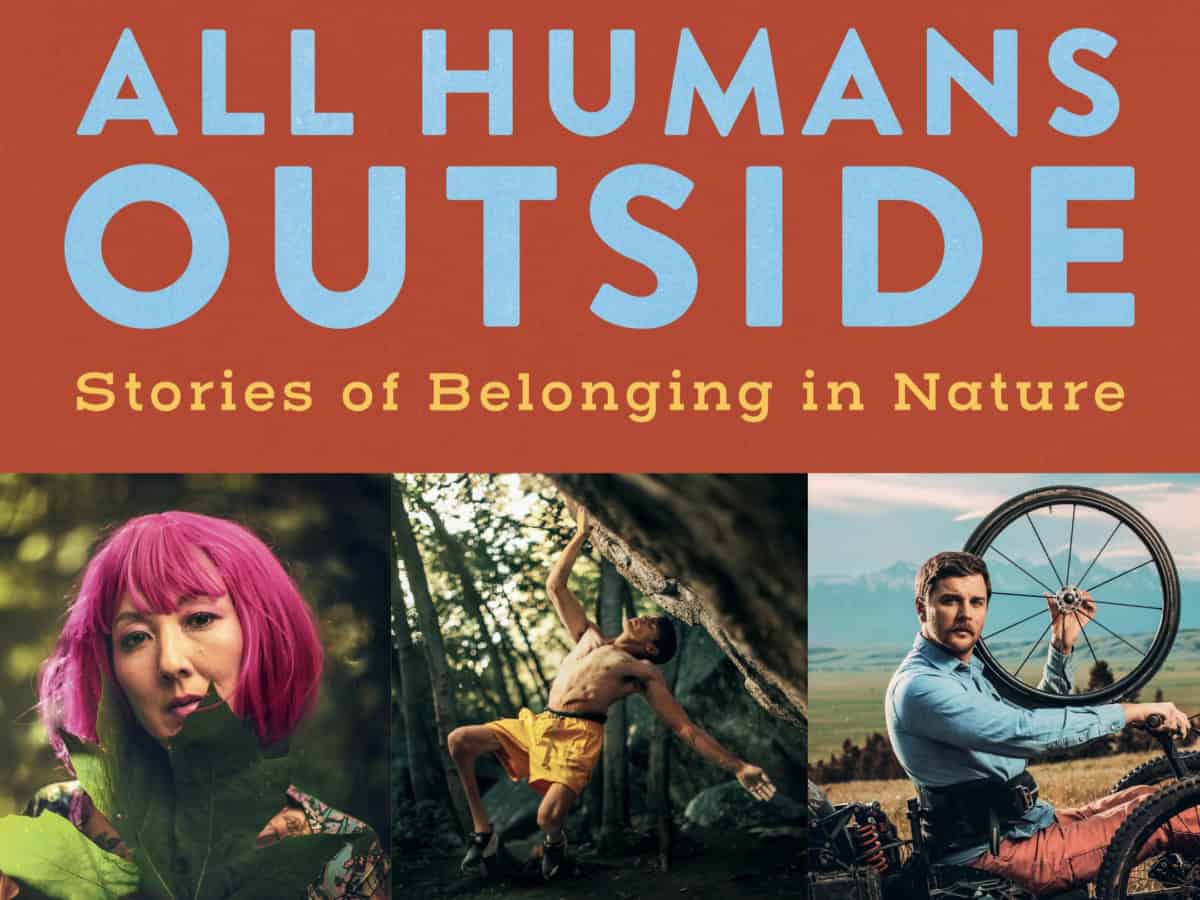

All Humans Outside: Stories of Belonging in Nature

Shaynedonovan Elliott

I WAS BORN DEAF, and throughout my life, I have felt a lack of connection to hearing people. Because of that barrier, I funneled all my energy into being outside and connecting to nature. Being around hearing people is difficult when you can’t understand or interact with what they are saying. However, when I am outside, even though the trees are not actually speaking out loud, I feel like we share a language.

I feel this unspoken language in photography too. As a deaf photographer, my entire world relies on my eyes. Photography helps me visualize emotions and use my eyes to communicate. It helps me place my own thoughts and feelings in expressive ways. I have been through so much in my life, so my art is a way of showing people that you’re not alone. My eyes are my language.

After my family settled back in the United States when I was a teen and I graduated from high school, I moved around to fifteen different states, seeking a place I could connect with. When I moved to Washington State, it felt like a place that truly fit me. I have ADHD, so having access to the outdoors allows me to keep moving. I was trying hard to work on myself, and nature gave me that sense of self-discovery.

When I planted my feet in Washington, I found it really hard to find people to hike with. I was coming out of a traumatic domestic situation and was feeling lonely, so I decided to adopt a dog to take on my adventures. When I started searching, I knew I wanted to adopt a deaf dog, because maybe we would be able to understand each other. After an internet search, I found a deaf Dalmatian. When I contacted the seller, they informed me a family had adopted the dog. But after two weeks, they reached out to say the family backed out, and he was mine if I still wanted him.

A week before I got my dog, I was on a hike with my friend Lacey. Deaf and blind, she had become my best hiking buddy in Washington. On that hike, I told her, “I am going to name my dog after you.” Sadly, she committed suicide shortly after that hike, which was really painful for me. I drove to Louisiana for her memorial service and then to Chicago to pick up my new companion. True to my oath, I named him Lace.

When I picked him up, he was jumping all over me, and I immediately felt such a connection to him. I started taking him hiking all the time, and he helped me begin to find myself. Although we had this beautiful friendship, I still found myself struggling with depression from everything that had happened in my life.

One night, in an act of desperation, I was getting ready to end my life. I looked at Lace, a rope in my hand, and he looked back at me. As we stared into each other’s eyes, something was different, because I felt like he was speaking to me. Without words, he was saying, “I know that I need you, and I know that you need me too.” From that moment on, I felt like we were closer than ever. We understood each other. He saved me.

The language I speak with Lace is hard to explain. All I know is that there is an undeniable connection between us. In that moment of despair, I knew that it was not just about me; it was also about Lace. After that, every time he came up to me, he would stare at me and talk to me. He could hear what was in my mind, and I could hear what was in his. We would look into each other’s eyes, and what transcribed was a silent language.

The communication between me and Lace feels like my conversations with nature. It’s not audible or spoken, yet there is an exchange of energy. When I am walking through nature, the trees tell me things like how many centuries they have existed or that I am going to be okay. They feed me positive energy and absorb the bad. Although I can’t hear, I can feel, communicate, and see-listen to a language that transcends the barriers of sound.

Anastasha Allison

AS A SPECIAL AGENT FOR THE RAILROAD, part of my job was to educate people about staying safe in the vicinity of trains. My job required me to endure a lot of trauma-in five years I handled seventeen fatalities. I was at a low point in my life and career and couldn’t get myself out. One January, I was driving home from a snowshoeing trip with my mom and my husband, Aaron, at Stevens Pass, a rural mountain pass in the heart of the Cascade Range in Washington State.

It was a clear day, but it was barely ten degrees. I must’ve hit black ice because suddenly, we were spinning across the four lanes of Highway 2 in the path of an oncoming semi-truck. Miraculously, our vehicle came to a stop, we didn’t hit anything, and no one was hurt. To this day, I can’t explain how things ended the way they did.

Although we walked away physically unscathed, my mom and Aaron did not have the same experience that I did. They said we were lucky to be alive, while I had experienced this profound out-of-body phenomenon. Many of those feelings were of guilt that my mom and Aaron were in the car, which made it difficult for me to go up to Stevens Pass afterward, due to trauma responses like nausea and a racing heartbeat.

Following this event, I went to lifespan integration therapy, which helped rewrite the memory. That helped me reflect and start looking at my life and how I lived it. I began to notice all these places where fear was holding me back from pursuing the things I was passionate about specifically the outdoors. Soon after, I quit my railroad job and decided to take this wild idea I had dreamed up just a year earlier and dive headfirst into making it a reality.

My company, Kula Cloth, is an antimicrobial pee cloth designed for outdoor lovers who squat when they pee. The idea for Kula Cloth was conceived while I was backpacking the Wind River High Route in Wyoming. I had been a backcountry instructor for a nonprofit that taught backpacking skills to women and was wildly frustrated with how much toilet paper I saw in the backcountry. So, I started researching Leave No Trace toilet paper options and heard about using a pee cloth to reduce waste. It sounded disgusting at first, but for the love of nature, I decided to try it-and I loved it.

The Kula Cloth was intentionally designed to be a beautiful piece of art hanging on people’s backpacks. I wanted others to get excited about sustainability and talk about Leave No Trace, incorporate these principles and experiences they had in the backcountry into other areas of their life, and question whether their lives at home and the outdoors are sustainable.

Several years after that life-altering trip over Stevens Pass, Aaron and I traveled over the pass once again, this time on our motorcycles. We planned to get a bratwurst in Leavenworth, a Bavarian-style town east of the Cascades in Washington, while I delivered custom Kula Cloths to coffee shops in the area. There was a dramatic difference between this trip and the first one, the wake-up call my life had needed.

As we went over the pass, I noticed Union Peak, the mountain we climbed that day we almost got smashed by the semi. Over the motorcycle intercom, I told Aaron, “Hey, we’ve climbed that!”

“When did we climb that?” he asked.

“That’s the mountain we climbed the day of the incident!” I responded, smiling, realizing how much had changed since that day.

When I look back at that moment on the pass, I am thankful it happened because it was one of the most pivotal days of my life.

Tasheon Chillous

“YOU BREATHE LIKE A DRAGON.” As a far person, I have heard a lot of disparaging comments throughout my life, but this particular one has always stayed with me. It made me want to hold my breath. When I reflect on all the gifts the outdoors has given me, providing solace during times of trauma and the space to grieve, breath is an essential component of my relationship with nature.

If something is on my mind—anger, frustration, sadness, grief—I release it. I consciously exhale to let go of those feelings. Being outside and breathing has always helped me work through those emotions that hold on to me so tightly. Nature is the place I could expel my grief, an understanding solidified through the loss of my brother, Jason.

Jason died in early 2018 from various health complications originating from kidney problems he had from a young age. In May, just a few months later, my grandmother passed away, and by June, I found myself at the bottom of my lows. My pain only grew when my grandpa passed at the end of 2018 on New Year’s Eve. However, though grief persisted, so did my love of nature.

Following that tumultuous year of profound loss, I started dedicating more time to getting outdoors. I worked myself up to more challenging hikes because, for me, doing the hard thing always seemed to alter my life’s course. Finally completing the Loowit Trail, which circumnavigates Mount St. Helens in Washington, became a turning point. During that hike, I decided I wanted to become a personal trainer to share this gift of movement and freedom. A few months later, I successfully passed my CPT test and started working.

Movement and fitness have always been a big part of my life. Standing amid all the history and beauty the landscape around Mount St. Helens bears helped rebuild my relationship with the outdoors and with movement. Being a fat person in fitness spaces like gyms or trails can be triggering. Whether in person or online, I provide a space for my clients to learn how to work on their relationship with movement in a liberating and comfortable environment.

Being surrounded by others who share similar experiences and identities in the fitness space, whether they be fat, queer, or BIPOC, fosters a sense of safety rarely found in other communities. Many of us share deep-seated fears of being outdoors, apprehensive of people complaining that we take too long, take up too much space, take too many breaks, eat the wrong kind of food—or breathe too loud.

Nature has fundamentally liberated me, allowing me to embrace my body and all its capabilities. Amid the trees, the water, the myriad of tiny and giant creatures—the curves of nature—I find liberation in being a part of it all. I see myself as nature in all its beautifully diverse forms.

When I think about my trauma around movement, its focal point has always been breathing, which I think is ironic, because I love moving my body to the point of breathlessness. I just let others stifle my breath for so long. Taking in a deep breath while I think of those lost, like my grandpa, my grandma, or Jason, and then releasing that breath is beautiful and cathartic. Nature has always allowed me to inhale and exhale, providing space to process all my grief. But most significantly, out of all the gifts it has bestowed, it has given me the freedom to breathe.

Tommy Corey is an LGTBQ+ Mexican-American photographer whose creative endeavors focus on diversity, inclusion, and accessibility in the outdoors. His work has been featured by Outside, Gear Junkie, PetaPixel, This Is Range, the Pacific Crest Trail Association, and many outdoor nonprofits. His thru-hike of the Pacific Crest Trail led to a wholehearted devotion to the outdoors. Corey is based in Redding, California. Visit him online at tommycorey.com.

Tommy Corey is an LGTBQ+ Mexican-American photographer whose creative endeavors focus on diversity, inclusion, and accessibility in the outdoors. His work has been featured by Outside, Gear Junkie, PetaPixel, This Is Range, the Pacific Crest Trail Association, and many outdoor nonprofits. His thru-hike of the Pacific Crest Trail led to a wholehearted devotion to the outdoors. Corey is based in Redding, California. Visit him online at tommycorey.com.

Excerpted and adapted from All Humans Outside by Tommy Corey (May 2025). Published by Mountaineers Books. All rights reserved. Used with permission from the publisher.

Book links: