Ross Lake: Recreation, Hydroelectricity and the Future of Water in the North Cascades

When we talk about drought in this country, one usually thinks of recent water rationing in California or kind of historic events that led to the Dust Bowl in the 1930s. Here in Western Washington, we tend to take water for granted. With nearly 50 inches of precipitation falling on the Skagit Valley annually, a lack of moisture is not a problem commonly associated with our region of the world. Yet, after the National Park Service issued a press release on May 3 stating that summer recreation on Ross Lake will be impacted by this year’s low water levels, it’s time to talk about water in Western Washington.

Ross Lake, a 24-mile long reservoir created by Ross Dam on the Upper Skagit River, has for many decades been a favorite destination of boaters and backpackers seeking access to some of North Cascades National Park‘s most remote and iconic mountains. With 19 boat-in campsites and several tailheads along the lake shore, the reservoir is a principle feature of the area’s summer recreation portfolio. Every year Seattle City Light, the dam’s administrator, draws down the water level in anticipation of the abundant spring rain and snow melt that typically fills the lake by the start of the summer season. But this year, a combination of low snow pack, above-average temperatures, and very little spring precipitation has led the hydroelectric provider to predict that the lake will not be full this year.

Following this pronouncement, the National Park Service has decided to rescind all overnight camping permits for areas accessed by Ross Lake, affecting hundreds of permit holders, including North Cascades Institute’s Youth Leadership Adventures.

According to the Park Service:

The typical pool elevation in July and August is between 1600 and 1602.5 feet. Currently, City Light estimates Ross Lake will be as much as 25 feet below those levels for the entire summer. The Skagit basin received only 4.4 inches of precipitation during February and March 2019, the driest March since 1992, compared to a 30-year average of 15.56 inches. Snow pack in the Skagit basin declined by 18% in March and was only 75% of normal (1992-2019) as of April 15.

In order to understand the issue at Ross, one needs to zoom out to examine both dam policy around maintaining water levels, and the larger climate issues impacting precipitation in our region. Seattle City Light, along with being a hydro-electric provider, also maintains decades-long commitments to balancing energy generation with environmental quality and recreation in the special ecosystem in which they operate. The reservoir is managed for flood control, recreation, and maintenance of migrating fish populations that require downriver water levels to remain at a certain level.

Former North Cascades Institute C16 Graduate Student Jihan Grettenberger explains this in her natural history research:

A challenge for Seattle City Light is to maintain Ross Reservoir at certain elevations. First there are flood control regulations set by Army Corps of Engineers stating that Ross Reservoir must be drawn down to have 120,000 acre-feet of storage. The reservoir drawdown begins after Labor Day, must be completed by November and maintained until March 15. Once the mandated flood control period has passed, Seattle City Light has to refill the reservoir to have it full by July 1 for recreation and aesthetic purposes, as part of the settlement agreement. Furthermore, the reservoir needs adequate water for migratory fish to access tributaries for spawning and to meet the downriver inflow requirements. Historically inflows peaked in May and June coinciding with the reservoir refill period. However, the shift in earlier snow melt and less runoff may make it difficult to refill the reservoir.

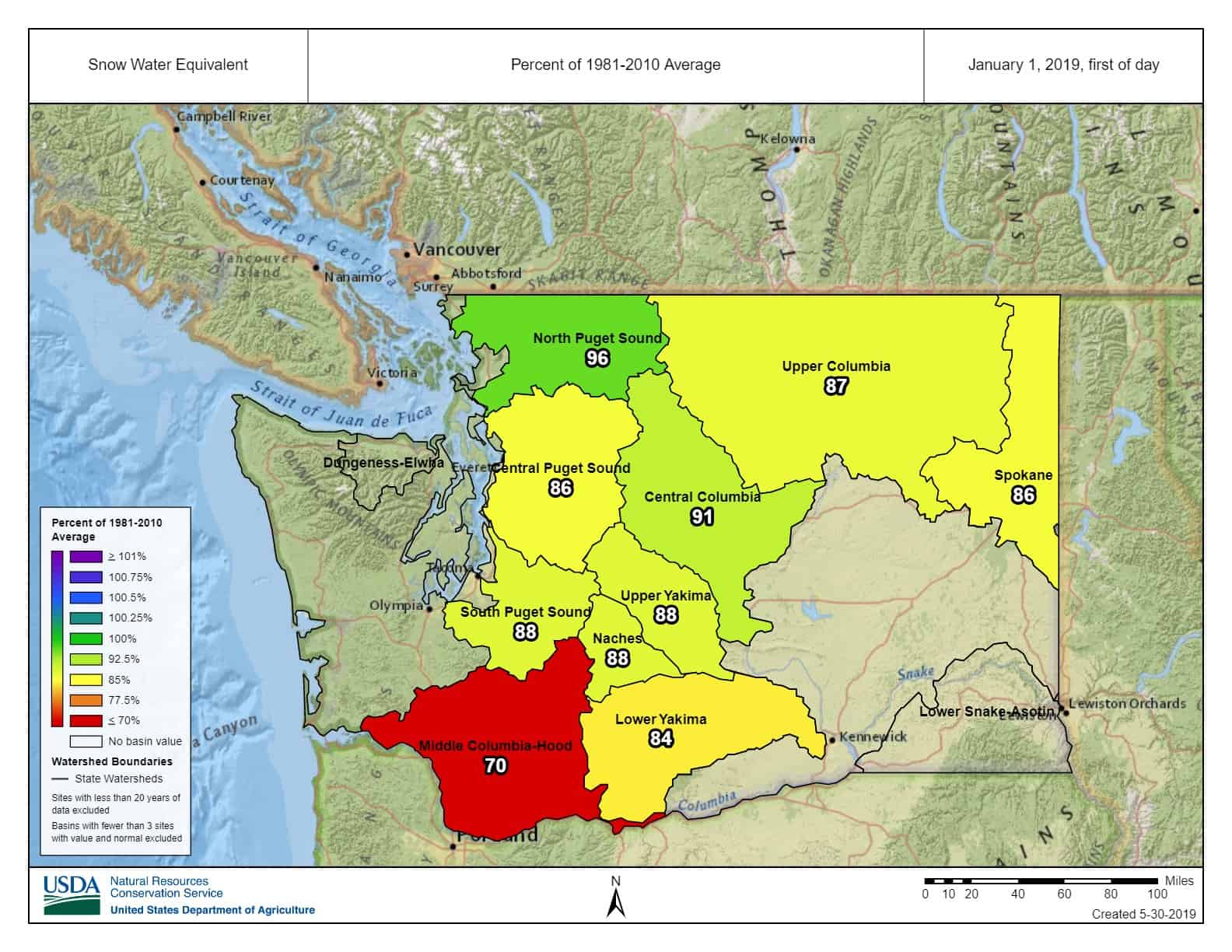

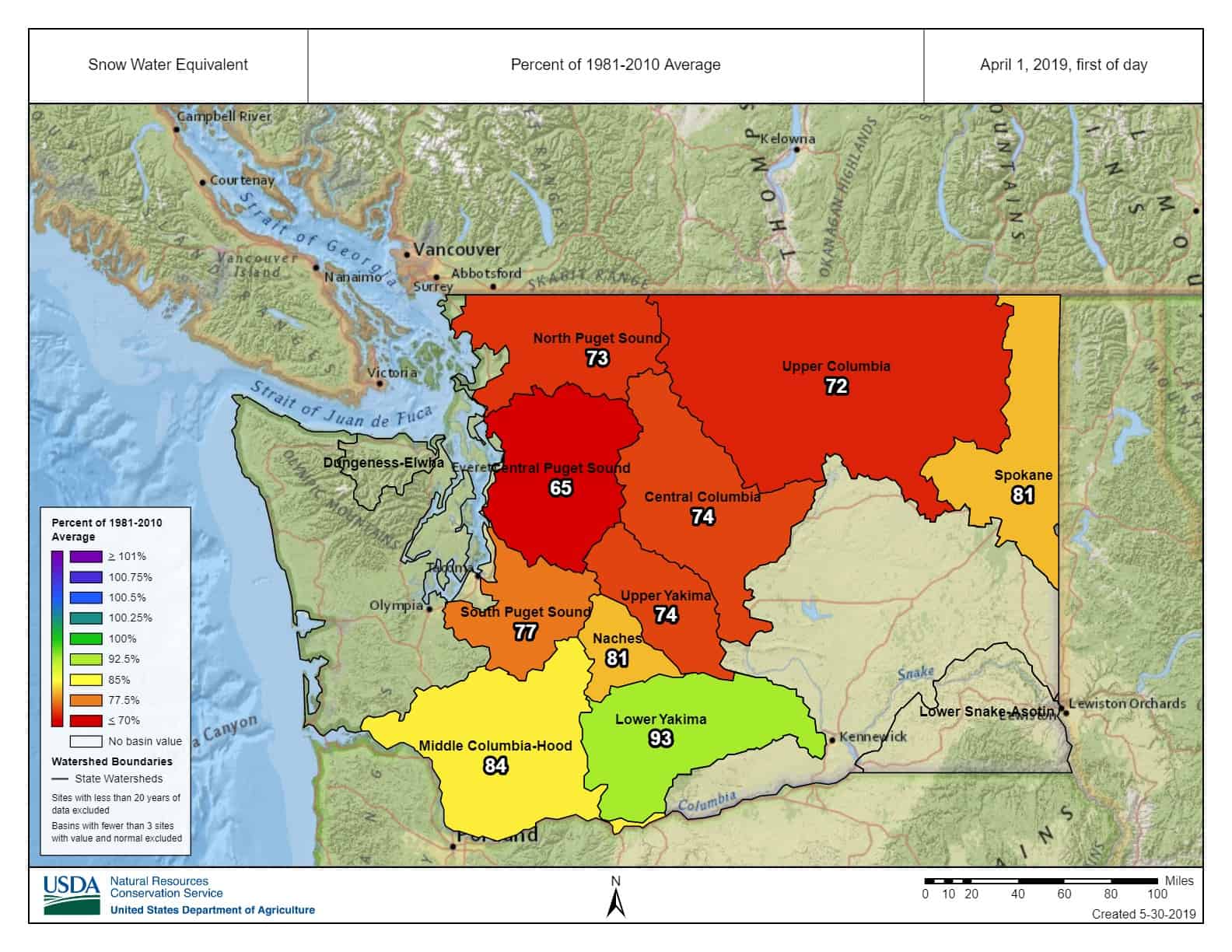

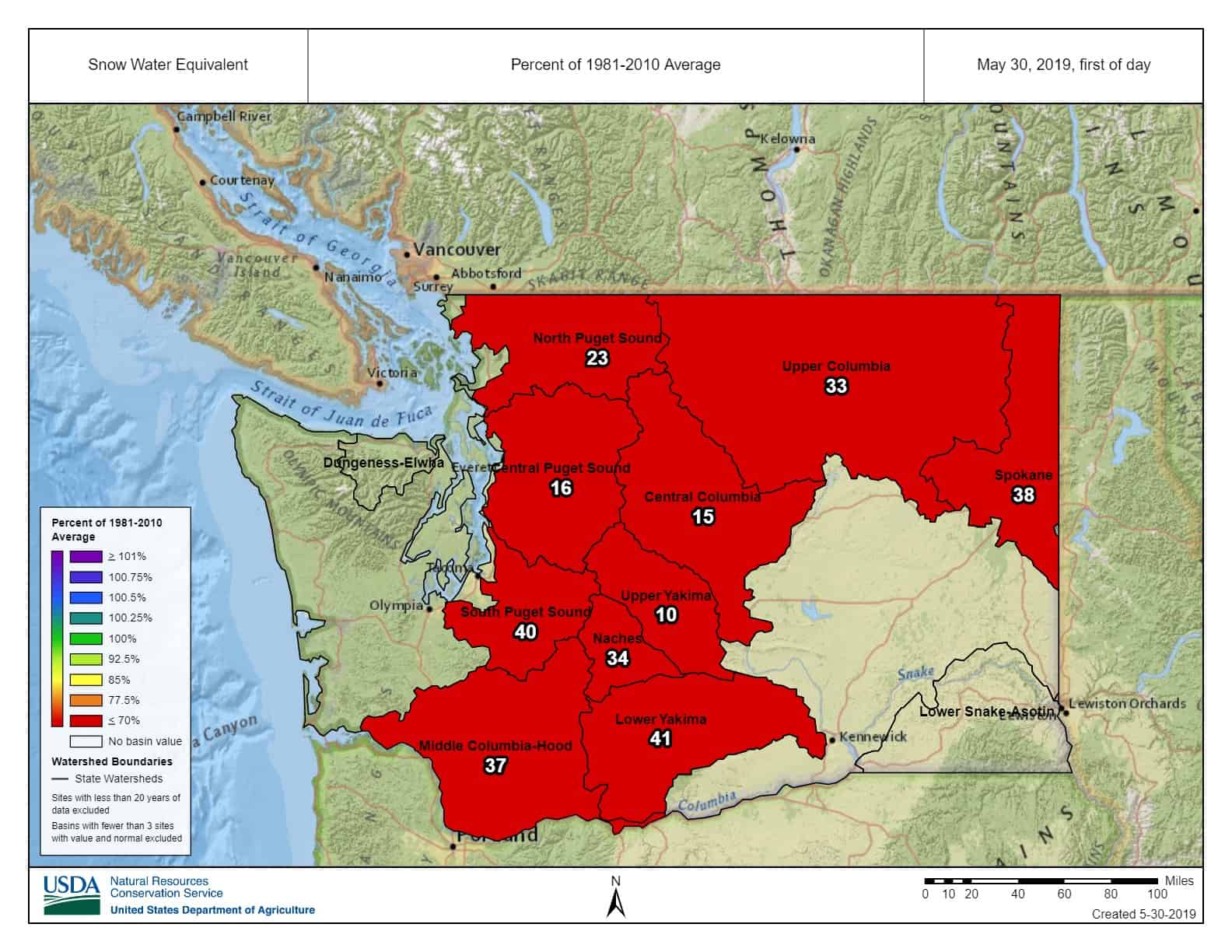

Indeed, at the start of 2019, Snowtel, the scientific monitoring system for determining and reporting the amount of water stored in winter snow-pack indicated that the Upper Skagit Basin was on track for a relatively average year. However, as winter transitioned to spring, the snow pack began to decrease dramatically, as illustrated in this series of interactive graphics generated by the USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service:

The lack of spring moisture this year is not just a issue facing the Upper Skagit, but, as the graphs illustrate, a state-wide concern as we enter the hotter, drier months of summer. On April 4, Governor Jay Inslee issued a drought emergency declaration for the Okanogan, Methow, and Upper Yakima watersheds. That declaration has now been expanded to include 24 other watersheds including the Upper Skagit and the Nooksack. Currently, 26 Washington counties are facing below 50% of average water levels, and long-range forecasts are predicting continued warm and dry weather through the summer months, and potentially into next fall.

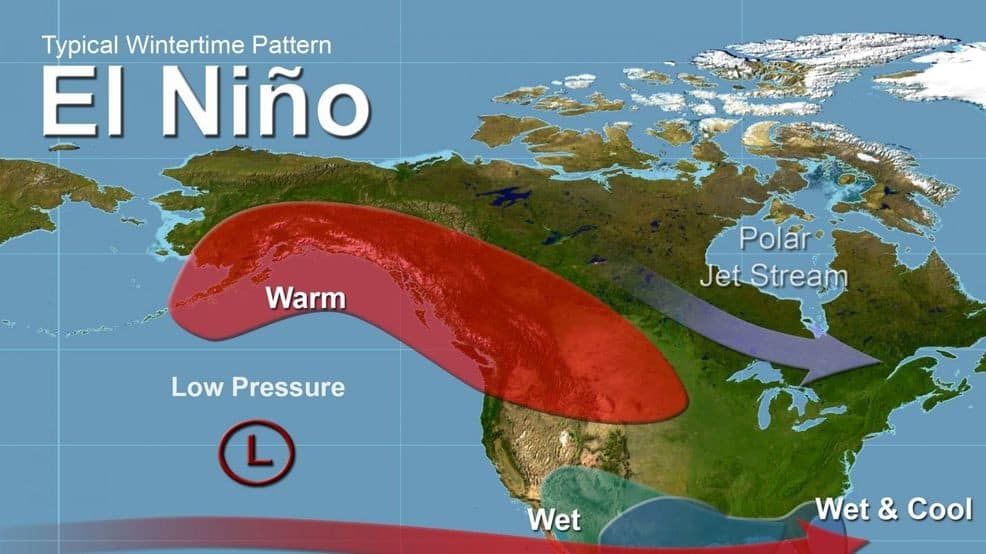

Part of the source of this year’s water shortage is likely the persistence of El Nino, an irregular weather pattern that carries warmer Pacific Ocean surface temperatures and dominant high pressure into the Northern region of the U.S. El Nino years are characterized by unusually warm and dry weather in the Pacific Northwest and cooler, wetter weather for the Southwest. This year, while not considered a strong El Nino, has certainly fit the typical model as California has seen a tremendous moisture increase from their drought-plagued years of the past decade. The current forecasts give El Nino a 70% chance of persisting through summer and 55-60% chance of persisting through fall.

While El Nino and drought years are not unprecedented in Washington’s history, the frequency and severity of these events seem to be increasing and linked to larger climate changes in the region. 2015 saw historic drought conditions and record acreage burned by wildfire. Now, just 4 years later, we seem to be set up for a similar scenario. Looking forward, Washington’s water supply will no doubt face more significant impacts as temperatures warm and the severity of weather events, such as droughts and floods worsen.

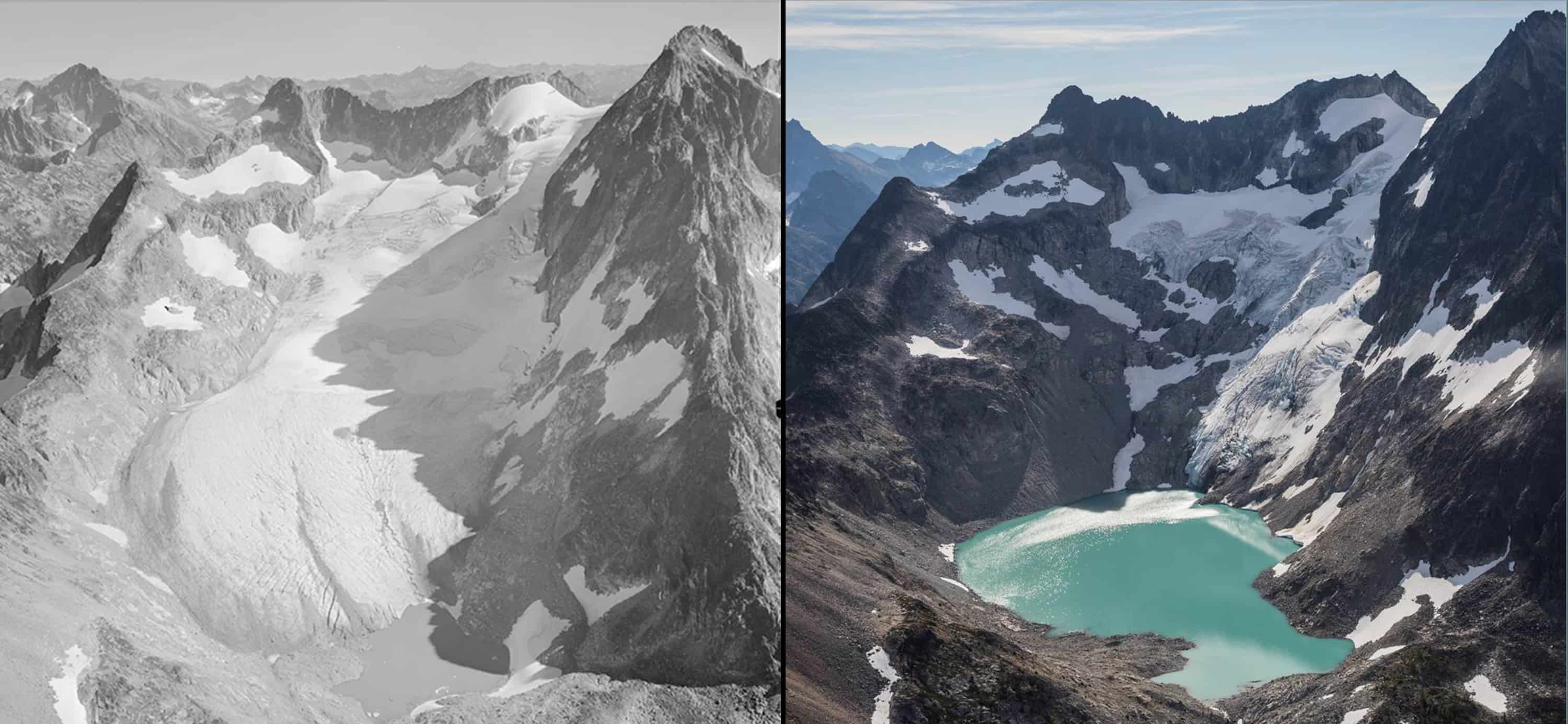

Lower snow pack, earlier spring melt, and more frequent and severe droughts are all predicted as we turn up Earth’s temperature. In addition, many hydrologists predict more flooding and higher water flow in winter months as more precipitation falls as rain, rather than snow, and runs off quickly rather than being held in the snowpack for gradual release. Additionally, glaciers, which provide 12-24% of late summer water supply and also bring down nutrient-rich minerals from the mountains, are losing mass at a rapid rate. Glacier mass has declined 19% in the Upper Skagit since 1959. It is unlikely that they will continue to be a reliable source of water in decades to come.

Water in this region is not just important for recreation, like the kind people enjoy on Ross Lake, but for almost everything we do. Watersheds in Washington provide roughly 70% of the state’s power through hydroelectricity. Fresh water is also an essential source of irrigation for agriculture, drinking water and habitat for salmon and countless other species that depend on our rivers and lakes. In addition, moisture levels in our forests predict the likelihood of wildfires, which are also increasing in size and frequency, effecting air quality and summer recreation around the state.

While we may not be able to predict future weather or climate events with certainty, we can educate ourselves on the trends that we have already observed, and adapt to the changes and challenges that we face going forward. Seattle City Light is already planning for future changes in water supply and flow that reflect more winter rain, earlier spring melt and lower summer runoff. Additionally, the Skagit Climate Science Consortium is providing research and education for the community on how observed and predicted changes will impact local residents. As for Youth Leadership Adventures, the program will still go forward as planned this summer, with modifications to the group’s trips that will include more backpacking and boating on Diablo and Baker Lakes but, unfortunately, no boating on Ross this year. The program does hope to bring students back to Ross Lake in the future.

We are lucky to live in a state and region with abundant natural resources, biodiversity, and stunning beauty. However, we should never be so naive as to take these things for granted or assume their limitless bounty. We have an obligation to future generations to work actively to ensure that our resources are managed for the health of all beings, current and future. With increasing human populations, the demand for water will also increase, and as our water supply becomes less predictable, the challenge is on us to continue to strive for balanced use of this essential, life-giving resource. Through education, conservation and commitment to a sustainable future, we can continue to live in abundance with this spectacular land that we call home.

This article was completed with the research of current Graduate Student Nicola Follis, and former Graduate Student Jihan Grettenburger. Special thanks for their hard work!

To continue to stay up to date with water and climate data check out these sources:

- Skagit Climate Science Consortium

- Climate Normals and Weather Almanac

- Snow water Equivalent % of Normal: USDA

- Skagit River Discharge and Temperature Data: USGS

- El Nino Southern Oscillation Climate Predictions: NOAA

As always, thanks for reading and click here to continue to support climate change and conservation education in Western Washington!

Excellent, informative explanation of the pressures on the resevoir. Is there a 2020 follow-up?