Glacial Mud and Deadly Landslides: A Legacy of Glaciation in Western Washington

It was a rainy morning on a cold, October day when I developed a new lens for reading the landscape of western Washington. I embarked from the Environmental Learning Center, at dark, with my North Cascades Institute nametag and field journal at the ready. The next morning, I found myself amidst a large crowd of unfamiliar faces and introductory chatter. This field trip was a celebratory event, to kick off the Annual Geologic Society of America Meeting in Seattle. Over fifty geologists of varying ages surrounded me, armed with rain gear and umbrellas. All had come eager to discuss the history of landslides in western Washington.

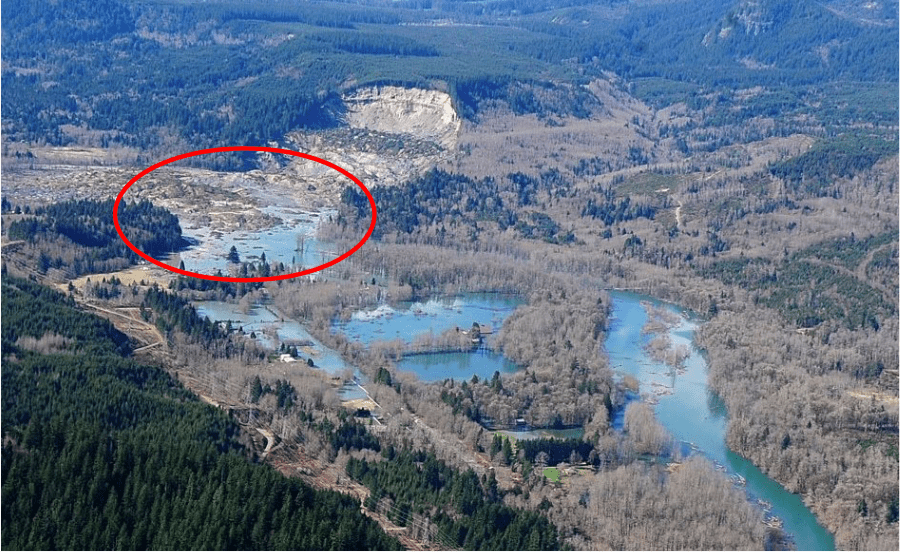

We met along the North Fork of the Stillaguamish River just outside of Darrington, WA. I had driven along this road many times, questioning the large gouge in the hillside, perhaps a gravel pit or mining operation? Hiking up a Forest Service road on the facing hillside, we cleared the valley floor and ascended to where we could see this large scour from across the river. From this vantage, the extent of the destruction was clear.

Our field trip focused on deep-seated landslides in Western Washington. The seemingly benign hills of the Stillaguamish River valley was the first crime scene; the site, we learned, of many past and recent landslides. Our purpose was to discuss the most recent Oso landslide, and to tease apart the story, and like forensic scientists working backwards at the scene of a crime. It was our task to determine if this destruction was likely to happen again.

The Oso landslide is the deadliest landslide to date in American history. Forty three people were buried alive. The slide occurred on a sunny Saturday morning, when children were home from school and parents were home from work. Forty three evergreen trees now stand planted along Washington Highway 530 which runs directly through the valley, the highway was also buried by 12 feet of debris during the slide. The fence in front is now decorated with wreaths and teddy bears.

In the wake of the slide, many fingers were pointed at the logging industry for decreasing the stability of slopes through clearcutting practices. Darrington hosts one of the last major commercial logging mills in an area where logging served as the primary economy for many decades. In the final legal settlement, Grandy Lake Timber Associates was accused of increasing runoff and making the property more vulnerable to landslides from a recent clear cut. Once a tree is cut, it takes about eight to ten years for the root mass to rot and the soil to destabilize. The forested land on the Whitman Bench above the site of the landslide was cut approximately ten years before the Oso slide. Grandy Lake Timber Associates contributed $10 million to the settlement, of approximately $120 million in property damage. Yet from a geologists’ perspective, the picture becomes wider when comparing the site of the Oso landslide to other places in the valley.

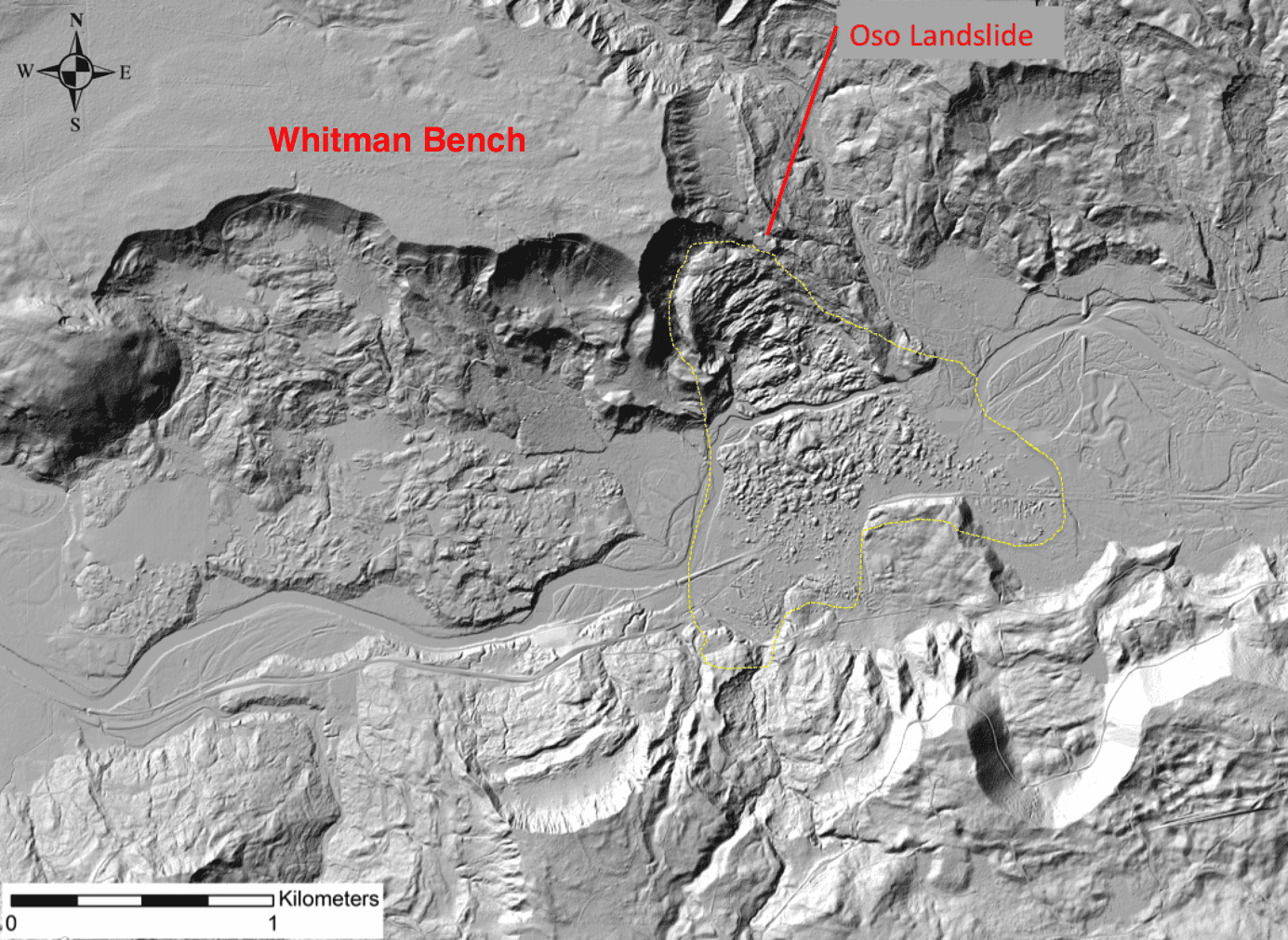

A key resource for teaching on this field trip was a set of high resolution maps created with a relatively new technology called “LIDAR.” LIDAR images are created by shooting millions of laser beams to the Earth’s surface, and like bats using echolocation, using differences in the return time of the beams to reconstruct topography. This resolution of this technology is so high that it negates the signal from vegetation, producing a geologist’s true dream: an image of the Earth’s surface without the interference of plants. The following LIDAR image illustrates how common landslides are in the Stillaguamish valley. The most recent Oso landslide is highlighted by a yellow dotted line.

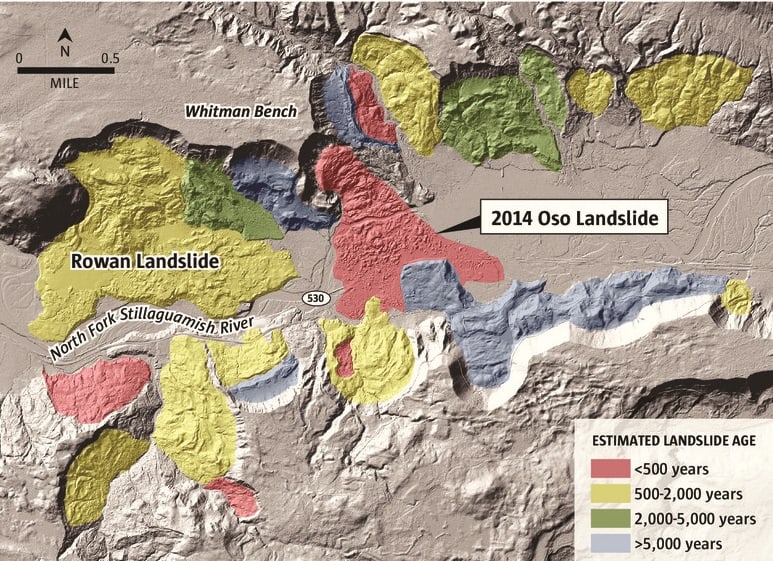

In fact, a closer look at the geologic record indicates multiple layers of landslides that have occurred in the Stillaguamish River valley throughout the last 5,000 years.

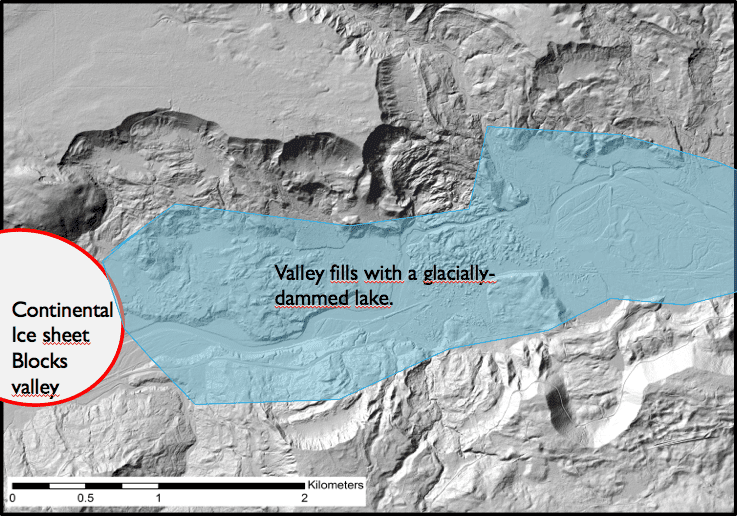

The fact that landslides are common in this valley hearkens back to its glacial history. Twelve thousand years ago, the Stillaguamish River valley was blocked by glacial ice, from a continental ice sheet over a mile thick that buried the Puget Sound. Channels of the Stillaguamish River have since cut down into geologic materials deposited by glaciers, including sediments of glacial streams or in glacially- dammed lakes.

As graduate students in the North Cascades Institute M.Ed. program, we had the opportunity to see some of these glacial sediments up close and personal.

The Skagit Valley, which runs parallel to the Stillaguamish, home to Concrete and Sedro Wolley is also filled with glacial sediments. These layers of mud, sand and gravel sit atop harder bedrock. It is this material that fills the valley floors, but also is steadily sliding away.

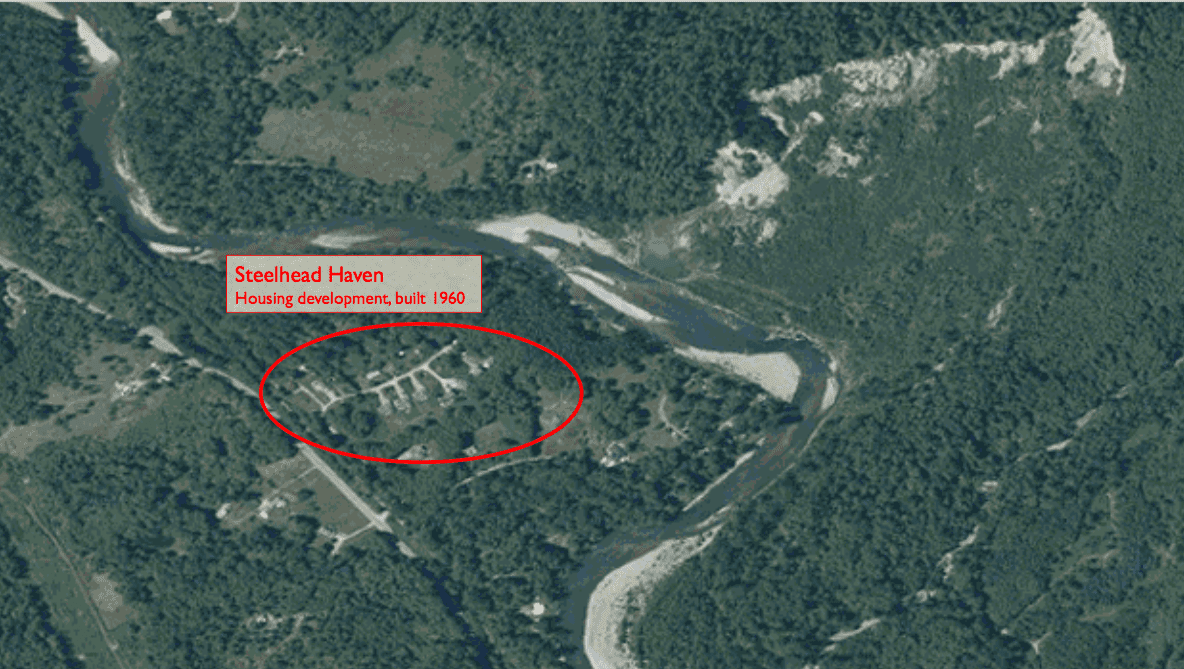

The question after the Oso landslide for geologists was; what made this slide so deadly? The housing development which was buried, Steelhead Haven, sat almost a mile from the valley walls and was not included in landslide hazard zone. Yet any geologic examination of the valley would have revealed that these walls were prone to collapse; a landslide occurred in the exact same hillside in 2006, just seven years earlier. Why did debris from the Oso slide travel so much further than the slide in 2006, far enough to bury the homes in Steelhead Haven?

My field trip to the Oso landslide site with the Geologic Society of America was partially led by David Montgomery, of the University of Washington. He was one of several folks hired to do geologic mapping of the Oso slide directly after the event and determine what happened. The post-slide evaluation produced by his group suggested that the Oso landslide had remobilized sediment that was already unstable from the 2006 slide.

The takeaway: landslides in this area are frequent. According to many geologists on this trip, “The glacial sediments [coating the valley walls] will continue to erode away until it is stripped down to more resistant bedrock. The next slide is only a matter of time.”

Thank you to the North Cascades Institute for providing funding assistance for me to attend this conference!

In October 2017, thousands of geologists from around the US (and the world) descended upon Seattle for the Geologic Society of America Annual Meeting. It is an opportunity to share research, network, and, most importantly, host field trips to sites of geologic interest in the area. As a graduate student at the North Cascades Institute, I was excited to participate in the conference and share my work as an educator, geologist, and now local resident of the Pacific Northwest.

A link to a press release about the conference and research on the Oso slide can be found here:

http://www.geosociety.org/GSA/News/Releases/GSA/News/pr/2017/17-55.aspx

For more information on how scientists are studying geology and natural disasters in Washington State, check out this cool, new resource from the Washington Department of Natural Resources State Geologic survey:

https://wadnr.maps.arcgis.com/apps/Cascade/index.html?appid=36b4887370d141fcbb35392f996c82d9

Thanks for this article Gina! I appreciate how your discussion of glacial history adds complexity to an often over-simplified event. Also awesome to hear that you got to go to this conference through NCI! 🙂

Thank you Emily! Always great to hear word from a fellow geologist 🙂