It's the COMpost!: Welcome to the Black Morel

During a recent celebration at the Environmental Learning Center, I noticed Saul, our Executive Director, gesturing toward the compost building from the back deck of the dining hall. Made of grey cement blocks and housing two Green Mountain Technologies Earth Tubs, a dumpster, and several recycling bins, this building is where dining hall leftovers are transformed in to nutrient-dense fertilizer as part of the North Cascades Institute’s Foodshed program. The structure is hardly architecturally or intellectually noteworthy. And it stinks. So what were the dozen or so revelers talking about, captivated by the most infamously fragrant building on campus as opposed to, say, staring west through the trees at a twilit Diablo Lake as the sun descended into the folds of the glorious Skagit Valley?

Saul explained he would like for people to start calling the structure by its rightful, well-earned moniker. “It’s named ‘The Black Morel’,” he said, with all the authority an executive director can possess when referring to his facility’s odiferous refuse.

Perhaps you, dear reader, have noticed that every building on campus has a name, all which reflect the native vegetation, save for our one fungal representative – the Black Morel. The waste management building represents an entire other biologic kingdom, one that is neither plant nor animal, deriving it’s food and energy from dead things and helping them turn back in to soil. This naming of the buildings was completely intentional. Saul said that initially, while building the campus in 2004, they were referred to by a quick and boring “Building A, B, C, etc.” But why not integrate the built environment into the living one as much as possible, and use them as teaching tools as well? Towards that end, for example, there’s Sundew, our Aquatics Lab, named after a bog-loving carnivorous plant that looks like a monster’s toothy mouth. Or consider the Wild Ginger, our cozy library, named for a plant with heart-shaped leaves that lie close to the ground, with inconspicuous, triangular maroon flowers hiding underneath, much like books, full of love and secret worlds.

The namesake fungi: the Black Morel (Morchella elata). Photo by Lee Whitford.

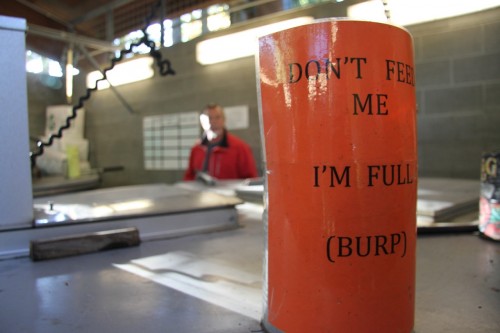

Where the loop gets closed. Photo by author.

Where the loop gets closed. Photo by author.

I vaguely recalled noticing the carved wooden sign announcing the building’s given name. I still referred to it, though, as most of the staff did, as “the compost.” That was how it announced itself, olfactorily, whenever one ventured near that edge of campus.

But Saul was right. Though the office (a.k.a “Twinflower”) is where all of our programs get organized, and our trails are where about 2,500 Mountain School students every year get connected to this North Cascades ecosystem, the Black Morel may be the most important place at the Environmental Learning Center. It’s where the loop is closed, where the cycle of matter and nutrients works perfectly, rather than getting ignored and abused in the typical “trash” to landfill scenario. According to our chef, Shelby Slater, all of our food waste is composted, and 75 percent of the total waste from the kitchen ends up here (of the other quarter, 15 percent gets recycled, and only ten percent is destined for slow death in the landfill).

There’s the “foodshed” cycle, too: Blue Heron Farm in Rockport and Acme’s Osprey Hill Farm provide much of the food that gets prepared and served at our dining hall. The carrot tops and leftover scraps go to the Black Morel, where they are transformed into fertilizer to give back to local farms, the Angele Cupples Community Garden in Concrete, and private down-valley gardens.

Anne Schwartz, of Blue Heron Farm, showing off a leafy and lovely bok choy in front of a field of organically-grown corn. Blue Heron provides much of the food served during programs at the Environmental Learning Center. Photo by Michael Brondi.

Anne Schwartz, of Blue Heron Farm, showing off a leafy and lovely bok choy in front of a field of organically-grown corn. Blue Heron provides much of the food served during programs at the Environmental Learning Center. Photo by Michael Brondi.

This simple efficiency makes Black Morel the most elegant building on campus. One of my favorite parts of Mountain School’s three-day Ecosystems Exploration curriculum is taking my trail group there after learning about foodsheds from Chef Mike at the end of Day 2, a.k.a. “Biotic Day.” It is also one of the most challenging. Convincing a gaggle of fifth-graders that it’s a worthy plan to hang out amidst rotting food, their nostrils burning with the sharp stench of decay emanating from the twin, six-foot diameter tubs, is no breezy task.

But since Mountain School is all about engaging the senses, the visit is practically requisite. After checking for wayward plastic packaging, the students chuck their used lunch bags into the tubs. How cool is it when the students love this experience? When the most high-maintenance, “Ew, gross!” participants sticks their hands deep into the slimy mélange of apple cores and old pasta to feel the heat energy given off from billions of bacteria enjoying the buffet?

If I can keep the students in there another couple minutes, they get the opportunity to help the microscopic organisms with whom they share this planet, turning the compost in big circles like a merry-go-round of collaborative, interspecies decomposition. Hopefully by this time, the offensive reek has mellowed (sometimes it becomes almost sweet), and they’re laughing and loving it. If they allow for another 30 seconds, they can feel the finished product — the nutrient-rich organic fertilizer, black and fluffy, not at all resembling the rotten rainbow of food scraps and paper napkins from Mountain Schoolers just like them a few weeks previous.

Brad Tuininga, Resource Development Director at the North Cascades Institute, grabs a tong-ful of decomposing food waste. Occasionally, plastic bags or those ubiquitous stickers on apples sneak in the mix and have to be hand-picked out. Photo by Jessica Haag.

Brad Tuininga, Resource Development Director at the North Cascades Institute, grabs a tong-ful of decomposing food waste. Occasionally, plastic bags or those ubiquitous stickers on apples sneak in the mix and have to be hand-picked out. Photo by Jessica Haag.

Occasionally, if needed, I will mention that havoc-wreaking students can get transferred from their deluxe, amber-lit lodges (named after native conifers) for a complementary night in the esteemed and steamy Black Morel.

Contemplating compost, I can’t help recalling the Pirates of the Caribbean movies, in which Johnny Depp’s character, Jack Sparrow, is trying to get his precious ship, the Black Pearl, back from rival buccaneers. Aarrg, the Black Morel! Our building, and our role, is similar to an oyster’s magic of turning sand into a precious treasure. And though we are neither pirates nor bivalves, we are laying claim to riches usually plundered and underappreciated, compacted and buried under mounds of ever-more refuse in our society’s mile-long middens. In a world without decomposition, life on earth would quickly cease, smothered under piles of maple leaves and animal carcasses. No nutrients would return to the system, instead forever locked up in a dead organism. We Americans typically don’t like to think about death, so we don’t. Yet the two – life and death – are inseparable, and are ecological necessities. It is time to honor that yin and yang, and celebrate decay.

So here’s to the Black Morel, my favorite building on campus. Next time you’re visiting the Environmental Learning Center, make sure to swing on by for a stinky, and spiritual, experience.

Facilities Manager, John Harter, caught between the “hungry” Earth Tub and the gaseous full one. Photo by Jessica Haag.

Facilities Manager, John Harter, caught between the “hungry” Earth Tub and the gaseous full one. Photo by Jessica Haag.

Leading photo: One of two six-foot diameter, five-foot deep composters at the Environmental Learning Center. In an alternating cycle, this one is ready to receive food waste, while the other one is off-limits while the bacteria digest the soup of scraps. Photo by Jessica Haag.

Katherine Renz is a graduate student in North Cascades Institute and Western Washington University’s M.Ed. program. Someday she will have a cozy cob cottage named after her favorite decomposer, Amanita muscaria.