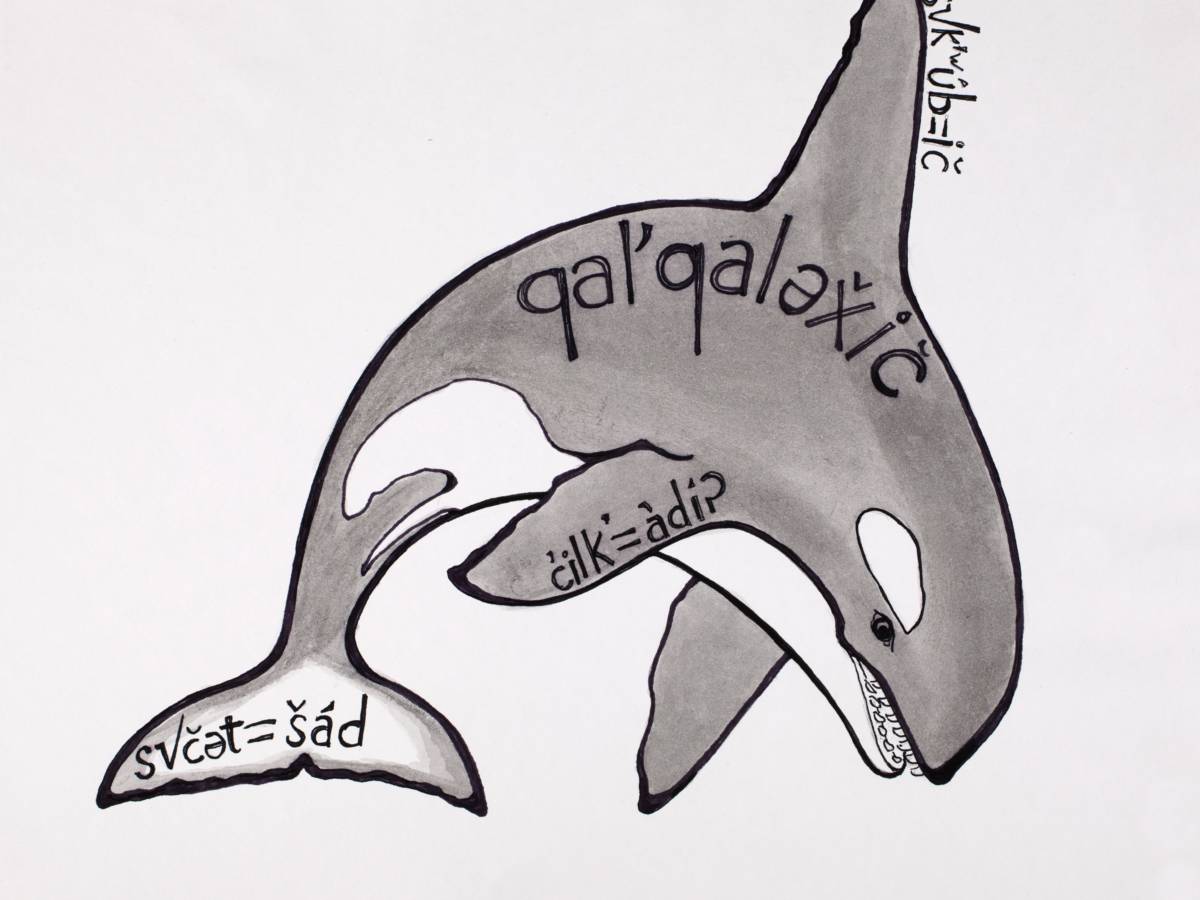

Meet the Bigg’s Killer Whale (Orcinus orca)

You see that fin slicing up through the surface—tall, tall, taller—until at last the body follows and an exhaled plume of breath huffs up? You know you’re in the presence of Killer Whale. Suddenly, the sea around you is enlivened, its mystery breached by the rise of this sleek, powerful body from the depths. For Native coastal people of Cascadia, this being—Blackfish, Orca, Killer Whale, Kéet, Grampus, Ska’ana—has always been an important community member, never eaten or hunted. Many stories and songs have been written and sung about Orca, and as you travel the waters of Cascadia, we hope you will seek them from Elders and storytellers.

If the Blackfish fin is the height of a Human, you’re looking at a mature male; if sickle-curved and about half that height, you have a youngster or a matriarch before you. Maybe you can even see the saddle patch, a paler, cloudy swoosh across Orca’s back, just along and behind the dorsal fin.

But is this Orca a Resident or Transient (now known as Bigg’s)? Fish eater or mammal eater? Or something else (Offshore)? Take a bit more time: look again. How many are in the group, and are they traveling close together or widely spread apart? Maybe you’re close enough to evaluate whether the saddle patch is open or closed, terms biologists use to describe the shape. A closed patch, which Bigg’s has, is solid, smoky white, with no black inside (Residents can have either open or closed patches). Drop a hydrophone and listen: Are they calling to one another constantly, or are they conspicuously silent? If there’s cavorting involved, are the pectoral flippers crazy-large? In all honesty, even such close observation might not bring you certainty.

Three types of Killer Whales traverse the waters of Cascadia, and although for a Human it can take time and careful training to distinguish them, these whales know each other well and easily by language alone. Genetically distinct for thousands of years, these ecotypes have different cultures, food preferences, and habits. It would not be surprising if, in the future, scientists declare them separate species.

Bigg’s Killer Whale specializes on marine mammals such as Dall’s Porpoise, Harbor Porpoise, Harbor Seal, and Sea Lion (they’ve been known to take Otter for sport and even, in a coordinated group, an adult Humpback or Gray Whale). The fact that Bigg’s Orca feed high up the food chain is, for them, both boon and burden. These whales carry the concentrated pollutants—PCBs and mercury—that all beings they’ve eaten have eaten. That females pass these contaminants along to their young in their milk is a particularly brutal fact in their matriarchal culture.

If you’re lucky and encounter these beings just after a successful hunt, one of them may approach your boat to show you a bit of what’s been caught, nosing a chunk of meat up to the surface as if to brag. Bigg’s Killer Whale, like all Orcas, travel in matriarchically led family groups; demonstrating success and technique to younger members of the family is an important part of their culture. In that moment, are you part of the pod? It is lovely to imagine so. We have much to learn from the journeys, conversations, cultures, families, and adaptations Orca has shared with us. We are lucky each time we have a chance to greet them.

Repatriation

for John Feller

A Killer Whale, you bend,

entering the Chilkat robe.

The hands of holders tremble.

The robe ripples

with its multiplying pods

of killer whales.

You dance

to an ancestor’s song.

The sea of killer whales

splashes on your back.

We can smell the sea

laced with iodine on beaches

at low tide.

— Nora Marks Keixwnéi Dauenhauer

Excerpted from Cascadia Field Guide: Art, Ecology, Poetry edited by Elizabeth Bradfield, CMarie Fuhrman, and Derek Sheffield (March 2023) with permission from the publisher Mountaineers Books. All rights reserved.

Thanks so much for the information!!

What are the other types of orcas called?