Playing With Fire: A Cultural History of Wildfire in Western Washington

When I was growing up in Western Washington summer was a glorious time. The cold weather and relentless rain would finally cease, and the warm embrace of that ever-elusive sunshine would wash over us at last. It was a time for picnics and running through sprinklers and long, endless days of adventure. I used to wish those days would last forever, and dread September, when the cold rain returned, and school resumed.

Today, I still look forward to summer adventures but with significantly more reticence than I did as a child. As the warmer months approach, I can’t seem to ignore the sinking feeling that, sooner or later, my summer fun will undoubtedly be dampened by sweltering heat, and unbearable smoke.

Fire is becoming an increasingly present force in Washington’s summer landscape. Large burns that force evacuations, and thick smoke blanketing our valleys are now a part of life in the west, more of an expectation than a notable event. Looking to the future, climate predictions forecast even hotter and dryer summers than the record-breaking years we’ve seen lately and it seems fair to say that even the soggy slopes of our western Cascades may not be spared from nature’s most rapid and aggressive agent of change.

As humans who live and recreate in Western Washington, we too will not be spared engagement in increasingly active fire seasons. Yet, to separate humanity from wildfire is to ignore centuries of evidence of their mutual life histories. To understand the natural history of wildfire in this region is to understand the ways in which human beings have sought to control, prevent, or benefit from fire on the natural landscape.

Since time immemorial, the human race has been captivated by the power and utility of combustion, and long before white settlers descended on this region, humans were putting fire to work on this land. For centuries, Coast Salish people of the Skagit Valley used fire, with annual burns in early autumn, to maintain open meadows and encourage the growth of various edible plants such as Common Stinging Nettle (Urtica dioica), Bracken Fern (Pteridium), and Camas (Camassia). Forested lands were also burned with regularity to promote the growth of various berries, an important food source, and Fireweed (Chamaenerion), used for weaving blankets. This had the added benefit of clearing the forest floor of onerous debris, reducing the risk of large wildfires, and promoting habitat for deer and elk.

Resource management through fire was not only a feature of lowland areas, but also of montane and subalpine zones as well. Fire use is well documented in many areas along the Pacific Crest from Oregon to British Columbia. The intent and effect of these burns took particular focus on huckleberries, a favored food of many peoples throughout the region. This periodic burning, undertaken at the end of the harvest, was a tool for maintenance of berry patches to improve productivity and discourage encroachment of trees and unwanted shrubs on the meadows. The burns were also beneficial to other alpine and subalpine plant species. This not only achieved a variety of industrial aims of people, but also produced a diverse variety of plant communities that have shaped alpine ecosystems to this day.

However, traditional burning practices were stifled with the arrival of white settlement in the area. The pervasive burning that took place in the Puget Sound area horrified early explorers and settlers, and as more settlers moved in, this activity was put to a quick halt. New federal land management agencies and industrial logging operations in the early 20th century viewed fire as a threat to timber harvest, and a general scourge that needed to be tamed.

Nationwide efforts to minimize fire, including the prohibition of anthropogenic fires by native people, were adopted and implemented on a nationwide scale. This policy persisted for most of the 20th century, and has altered the landscape in ways that are only beginning to be realized.

It is now a commonly held belief fuel loads in today’s forests throughout North America are much higher than they may have been if pre-contact fire regimes were allowed to persist. As a result, the likelihood of large, uncontrollable, and stand-replacing fire is more common today. It is also likely the case that the abandonment of indigenous land management practices has altered vegetation in areas where fire was once administered with regularity. There are many credible accounts of decreased abundance of root vegetables and berries, especially huckleberries and blueberries, in areas that were traditionally managed through fire, resulting in diminished biodiversity and lower berry yields for people who still use the sites for traditional harvests.

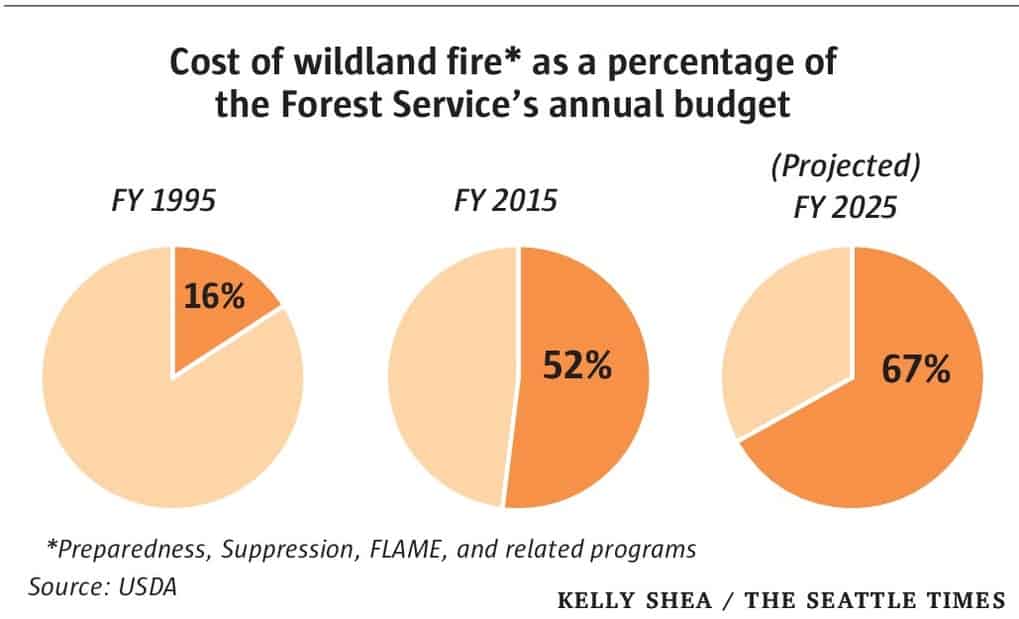

Though fire management policies have evolved from the archaic days of blanket suppression, we are still far from understanding the ways in which fire has always worked on this land. Public outcry over air quality and human safety have jettisoned idealistic notions of letting nature run its course and costly suppression efforts continue, at a cost nearly $2 billion annually nationwide, and half a billion dollars to Washington State since 2010.

While the future climate picture presents a grim picture, it is important to not overlook the significance of the human capacity to maintain and manipulate our environments and the lessons we can learn from the not-to-distant past. It is important to recognize that fire has always been on this landscape and whether or not we want it, it always will be. The people that inhabited this land for millennia before us knew this, and used its reality to benefit their existence rather than expend energy to fight an unwinnable battle against nature’s will.

Perhaps our salvation from a worsening future of relentless summer blazes threatening our homes and air quality, of diminishing biodiversity of our forests and parklands, is in learning this lesson: Humans and fire have always been mutually magnificent agents of change on the lands we inhabit. In many ways, we are rivals in our mutual power to consume. Yet we humans, in failing to vanquish this rival must now strive to avoid being consumed by it. Perhaps our way forward is learn from those who knew what we failed to see, that the land is better served if humans and fire work as partners rather than advisories.

This post was researched and written by Matt Ferrell for the Northwest Natural History course as part of the Institute’s Graduate M.Ed. program. North

Cascades Institute has not extensively fact-checked the information contained herein and recommends researching other sources of information to enhance one’s understanding of the topic.