On the Lookout for Unalloyed Pleasure: Poets in the North Cascades circa 1950s

North Cascade Institute’s graduate Cohort 13 recently hosted our annual Instructor Exchange with other students and teachers from IslandWood and the Wilderness Awareness School. As part of this, I facilitated a session about the handful of poets who served as fire lookouts in the North Cascades in the 1950s. My notes were gathered almost entirely from John Suiter’s comprehensive and lovely book, Poets on the Peaks (Counterpoint 2002). After the presentation was through, I realized my hunch was correct: People love these stories.

At this point, over half-a-century later, Jack Kerouac’s benzedrine-fueled fiction and Allen Ginsberg’s revolutionary (for the times) poems can seem romantic and co-opted to the point of being trite. Sometimes. More often, though, I regard this small club of men – Gary Snyder, Philip Whalen, and Jack Kerouac — who looked out, in solitude, from these mountains as an immense and symbolic source of relief. All three had connections and allegiances to the San Francisco Bay Area, a peninsula inhabited by freaks and artists and which regularly appeared as a setting in their writings. I, too, have been steeped in that place. It is a lifeline to know they lived and loved, wrote and pondered, here in the North Cascades, that they were the keepers of these ridges and valleys over a decade before these mountains were bestowed national park status. I can look up toward Sourdough Mountain, if it’s not hiding behind heavy grey, and hear Snyder and Whalen reminding me what a stunning land this is, assuring me that the steep streets of North Beach, the forested flanks of Mt. Tamalpais, the cacti gardens and Craftsman homes of Berkeley are a mere hitchhike away, should one choose.

The following relates three connected snippets of the poets’ experiences in the North Cascades. All information and quotes are from John Suiter’s Poets on the Peaks.

* * *

It is 1954, and Gary Snyder is not happy.

After spending two summers as a fire lookout in the North Cascades, once perched in the highest structure, atop Crater Mountain, and later living on the comparatively “suburban” Sourdough Mountain, Snyder’s application to work a third season is rejected by the United States Forest Service. Had the 24-year-old poet and mountaineer done something wrong? Perhaps he had not spent the requisite 20 minutes per hour scanning the horizon for smokes or failed to memorize every peak amidst his diligent practicing of Zen Buddhism, outlining a future play about lookout life, reading galore and imbibing green tea?

The view from Sourdough Mountain, looking north toward Ross Lake. Photo by Katherine Renz.

The view from Sourdough Mountain, looking north toward Ross Lake. Photo by Katherine Renz.

The answer is hardly definitive. On February 10, the Forest Service supervisor in Bellingham denies Snyder’s application on unclear grounds. Snyder eventually receives an explanation from the Department of Agriculture, vaguely attributing his dismissal to a “general unsuitability” as opposed to “security” issues. One thing is clear: Snyder is blacklisted from government work.

Homegrown campaigns against labor rights activists in Washington and Oregon got nasty after World War One, at times demonstrating a particularly Pacific Northwest brand of vigilante violence by flogging Wobblies with the spiky native plant, devil’s club (an ethnobotanical application of this highly medicinal species that usually goes unmentioned). Thirty-five years later, Snyder is irritated, hurt, and increasingly angry and frustrated by attempts to find other, equivalent employment. Senator Joseph McCarthy’s Red Scare is raging, and though the young poet is an open pacifist and anarchist, he is not involved in any radical organizing. Calling all pikas! You mountain goats o’er there, with your un-American beards! C’mon Hozomeen, rally the chert!

Plan B. Snyder sends a stack of applications all over the Pacific Northwest and California looking for summer work doing trail-building, fire crew, or fire-watch. He is successful, and buys six weeks worth of groceries on the way to his new lookout job in the Gifford Pinchot forest. He is fired the next morning. He finds a position as a choke setter on Oregon’s Warm Springs Indian Reservation instead. From Zen lookout-poet to manning one of the most dangerous jobs in the logging industry, Snyder’s season was a challenge.

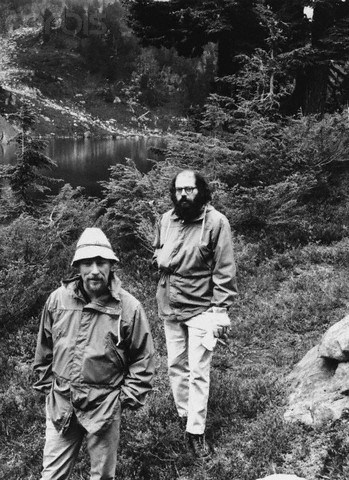

Though never a lookout himself, poet Allen Ginsberg [on right] was a friend and contemporary of Snyder, Whalen, and Kerouac. He writes: “Between June and September 1965, North Cascades National Park, Mount Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest, Washington State, USA — Summer 1965, 8 day backpack climbing in wilderness area of northern Cascades, Glacier Park, Washington state, [with] Gary Snyder [on left] back from a near-decade in Kyoto studying & practicing Zazen. My first mountain walk.” — Image © Allen Ginsberg/CORBIS

As Snyder writes in a letter to his friend, fellow poet and lookout Philip Whalen: “I am physically sick for wanting to be in the mountains so bad. I am forced to admit that no one thing in life gives me such unalloyed pleasure as simply being in the mountains.” And later, he elaborates: “Everything feels all wrong: I just can’t adapt to not packing up and traveling this time of year and my rucksack and boots hang accusingly on the wall.”

Philip Whalen’s boots, however, are indeed on his feet, though they are likely propped up on a chair, his lap supporting a book, more often than his mountaineering friend Snyder’s ever were. Set above 6000 feet at Sourdough Lookout, it’s mid-August and Whalen is in his second season, occupying the one room home in which Snyder had experienced his own creative surge the year before in 1953.

Previously, Whalen had spent his premier lookout season on Sauk Mountain, with a choice view of the Picket Range, Mount Shuskan, and Mount Baker. The two men, both writers, became friends while students at Reed College in Portland, Oregon. Highly intellectual, Whalen is turned on to lookout-ing by the younger Snyder, thrilled not so much by the physical challenges of the outdoors but by the rare opportunity to embark on an intensive summer reading campaign while living embedded in beauty and solitude to inspire his writing. And getting paid by the Eisenhower administration to do it! Snyder also introduces Whalen to Zen teachings and practice.

During his short stint in 1954 atop Sourdough (fire danger is low that year, and the season starts late), Whalen’s neighbors include a herd of a dozen stags and a resident black bear. Upon returning to the valley, motivated and enthused, he writes in a letter to Snyder: “My imagination is in great shape. Goodness knows what will happen next.”

A classic image of Diablo Lake, as seen from the flanks of Sourdough Mountain. In his poem “Sourdough Mountain Lookout”, Whalen describes it as “two lights green soap and indigo”. Photo by Katherine Renz.

A classic image of Diablo Lake, as seen from the flanks of Sourdough Mountain. In his poem “Sourdough Mountain Lookout”, Whalen describes it as “two lights green soap and indigo”. Photo by Katherine Renz.

It is a little over a year later, October 1955. A handful of poets, on fire, give a reading at San Francisco’s Six Gallery. Allen Ginsberg unleashes his incendiary “Howl”. Jack Kerouac, a writer and train-hopping Buddhist who’d recently arrived from a literary bender with William Burroughs in Mexico City, is in attendance, too. It proves a legendary night, the kickoff of the literary resurgence fueled by the so-called Beat Generation (not all participating poets, Snyder included, would enjoy this lasting label).

Whalen shares his tales of lookout work in the wild North Cascades to Kerouac. Snyder elaborates. Though Kerouac has never traveled in the backcountry before, he has long fantasized about holing up in a hermitage – writing rapid-fire, beset with visions, privy to a direct line to the divine. His experienced friends encourage him to apply.

Kerouac is accepted to man Desolation Lookout, a stone’s throw from the Canadian border, for the summer of 1956. His anticipation is overwhelming, and he tells his friend, Carolyn Cassidy, “O boy, O boy, O here I go, I got the offer for the job watching fires…and I told the Forest Ranger I hoped he’d take me back next year, and the next, and all my life. It will be my life work…”.

May 1956, Kerouac at Gary Snyder’s going-away party (Snyder would be back and forth between Japan and California for the next 12 years) in Northern California. This is six weeks before Kerouac left for his season in the North Cascades. Image © Walter Lehrman.

May 1956, Kerouac at Gary Snyder’s going-away party (Snyder would be back and forth between Japan and California for the next 12 years) in Northern California. This is six weeks before Kerouac left for his season in the North Cascades. Image © Walter Lehrman.

Being a fire lookout does not become Kerouac’s life work. He writes a ton while on Desolation (his arguably most famous novel, On the Road, would be published a year later). But he is also lonely, scared of the looming Hozomeen, especially in the dark, having more delusions than visions and yearning more for debauchery and drugs upon returning to the city than for the dharma of the present. In his 63 days on the aptly-named mountain, he receives no visitors, his sole social contact being when he scrambles down to the Ross Guard Station, ten days into his season, to scrounge a one pound tin of Prince Albert rolling tobacco from the generous guards.

* * *

Three men, 360 degree views, a slew of haikus, tales and legends. It is 2014. I look to the peaks and they rumble poems.

Above and top images © North Cascades Institute

Above and top images © North Cascades Institute

Katherine Renz is a graduate student in North Cascades Institute and Western Washington University’s M.Ed. program. She is looking forward to an obligatory pilgrimage to Desolation Peak this coming summer vacation, followed by a drink in North Beach.

Great posting Katherine! Nice to see the connection between the North Cascades and the SF Bay Area.

I feel so fortunate to live, work, write and play in the shadows of the North Cascades, taking special pleasure knowing of the Poets on the Peaks who have come before me. Desolation Angels, Snyder and Whalen’s fire lookout poems, Tim McNulty’s Sourdough chapbook… these mountains definitely bring out the best in our wild scribes! Thanks for exploring your own connections to this range and for sharing them too.

Born of smoke and fire glow

In those blazing summers of long ago

Little mountaintop pagodas

Wooden cabs with cute cupolas

Guardians of the grand Sequoia

Douglas fir and ponderosa

Where vigil kept with eagle eyes

Spotted smokes of wild land fires

Called the word to those below

When lightning arced in brilliant bolts

Around the face of Roman Nose

Raven Roost and Sugarloaf

And oh those names played magic games

Roamed my mind and called my name

Called me up to Sleeping Beauty

Pyramid, Sun Top and Tyee

Wounded Doe and Bumble Bee

Curly Bear and Chickadee

But a silence slow descending

Told me of an era ending

And I wander in despair

Searching ridges wind swept bare

Little houses once sat there

They all have vanished into the air

Tell me, where is Bonnet Top

Three Brothers and Three Corner Rock

I can find no sign or trace

of Porcupine or Dirty Face

Bunker Hill lies in disgrace

Just memories to mark their place

Now the wind blows eerily

Through the ghosts of their debris

Through charcoal rails and melted glass

Rusted nails and powder ash

No Sourdough or Stampede Pass

Timberwolf or Looking Glass

I’ll take the trail to Termination

Tramp the dust of Desolation

Dollarwatch and Devils Dome

Noble lookouts long gone down

They were up when I was young

Sunrise, Clear West and Setting Sun