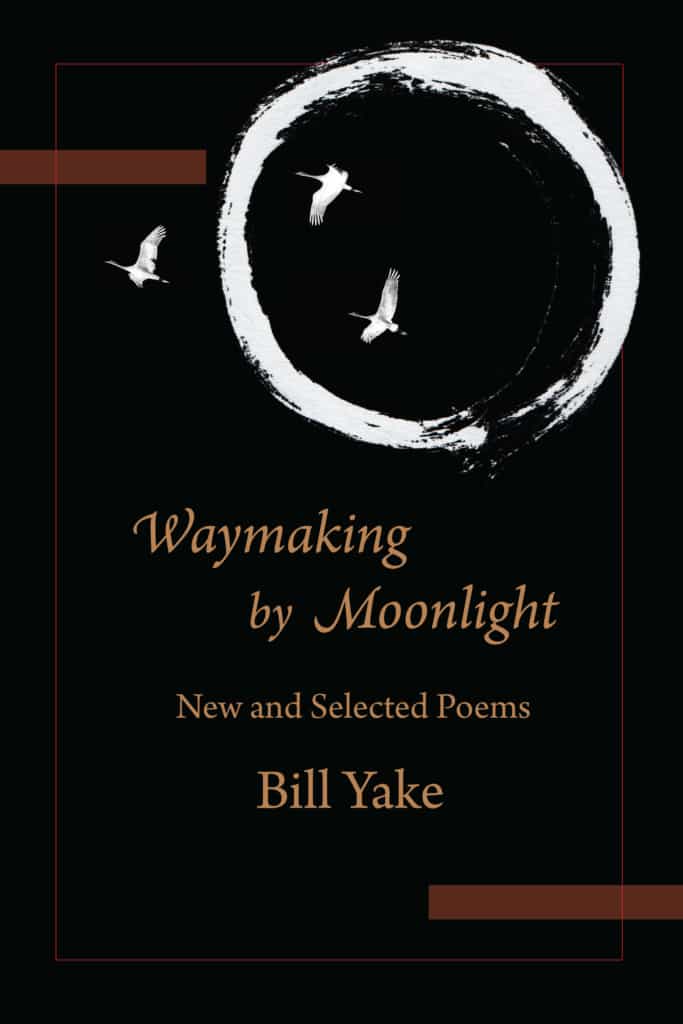

“Trails & Tracks; Poems and Memory” by Bill Yake

It’s a problem — pulling a collection of poems together. I had a friend who consulted a Tarot deck. Another who threw a sheaf of poems down a flight of stairs then gathered and stacked them as they had fallen.

It’s a problem — pulling a collection of poems together. I had a friend who consulted a Tarot deck. Another who threw a sheaf of poems down a flight of stairs then gathered and stacked them as they had fallen.

I was walking the trail of shadows near Mount Tahoma (Rainier) – a place where warm, iron-and-magnesium-colored water rises to the surface. Walking, I puzzled over what to say about the organization of the collection I was working on. Walking and puzzling. In need of an explanation, a preface, something that might serve as a minimalist map and organizing principal.

Watching the trail-view evolve step-by-step: a bubbling mud-pot, an historical cabin with a walled-off spring, walkers – some silent, others murmuring, and then children shouting, a wet meadow, a pissed-off chickaree — then it came to me:

“A book is a trail the mind walks. A trail is a tale, a sequence the eye can read.”

This was the collection – a trail. An indirect trail, a reticulated trail, maybe even a maze — but a trail none-the-less. Fifty years of chance and intention, inherited maps and apt suggestions. Random attention paid to visions half-seen out of the corner of one eye or the other. Temptations — forks in the trail — rejected or accepted.

In some places the trail was well-worn, in others a faint game trace, and some portions of the trail were marked with cairns or blazes. [You may have heard of chumstick? Chumstick Canyon, Creek and Mountain just outside of Leavenworth? Referring to a Chinook jargon dictionary, it says this: “painted/marked wood/tree.” A blazed-or-marked-tree. Signs marking the route, the true trail. This seems the likely reason the lean and hardy salmon, those whose males have red blazes marked on their flanks and who spawn near the mouths of west-side streams, are called chum.]

Blazes marked Howard McCord’s classes at WSU in the late 60s and his kind of poetry snared me. Words that resonated with something between my vision-dream-and-analytical attention, between forest openings and philosophical musings.

Howard quoted Ludwig Wittgenstein[i], “Is the fact that someone genuinely thinks he means something a guarantee that there is something that he means?”

To which he (Howard) had responded, “…the intelligence of deer trails is greater than that of the speech of man.”

The intelligence of deer trails. Perfect. That had been the inspiration and epigraph for a poem called Tending Trails that was in an invocation at the beginning of the collection. Here is that poem – which is also presented as a video here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8ZV_gu1Z4do

Tending Trail

“…the intelligence of deer trails is greater than that

of the speech of man.” —Howard McCord

Through ravine and forest

we’re led by the mutual

intentions of foxes, racoons,

deer, and the predatory cats—

along the game-trails,

traces, and foot-paths

that track the phrenology

of the land: its stony skull and frame

and the direct, then winding, way

its creatures find from stream

to browse, from cover to clearing,

from safety to necessity.

We have joined that trek

—being curious and wanderers—

and scramble through the maze

at first, then place a stone

for a step where the way is steep

and set cedar rounds down

in swales where swamp lanterns

thrive, in the bottom-lands where

paw prints speak precisely of intent.

Later, we’ll return to brush out

sword ferns and the low cedar

fronds that crowd our tentative

human prowling; bring a mattock

to widen side-hill runs—to cut back

soil on the uphill slope, the sloughing

duff with its curled millipedes tucked

inside—the yellow-spotted, almond-

scented, cyanide-laced kind.

New fiddleheads and rich decay

will tumble from above. Then we

heap and smooth, widen and level,

rake and tamp the moist ground

down—retaining each substantial

root as foothold or intricate

step; leaving branch handles

intact to grasp—so when we come

this way, again, it will be only

a little less lightly

than the beasts.

So here’s an idea. Consider trails in your neighborhood, favorite park, or refuge. Or — more broadly — trails, paths, routes, rail tracks, and roads — maybe Robert Frost’s ‘two roads diverg[ing] in a yellow wood.” How they originated, how they affect the land use adjacent to them, the difference between gas- station-and-minimart views from highways and the back-and-railyard views from “passing trains that have no names.” How routes become fainter and fainter going from city to wilderness. Mine these musings for discoveries, stories, and poems.

They’re there. Whether on today’s walks or along trails you walk or tend in memory or imagination.

[i] “Walking Edges: A Book of Obsessional Texts” (Raincrow Press, 1982).

Bill Yake has been making and publishing poems that celebrate the nature of the Pacific Northwest since the late 1960s. He’s worked lookouts, road construction, and cemeteries; fought forest fires, and during his 25-year career with Washington State’s Department of Ecology as an environmental scientist and engineer, Bill diagnosed malfunctioning sewage treatment plants and tracked poisons in water, fish, and sediment. Paths have taken him into the mountains, the high desert, and the forests and prairies of the Puget Lowlands. His writings have appeared widely in publications serving environmental, scientific, and literary communities – these include Open Spaces, Orion, Rattle, Cascadia Review, and NPR’s Krulwich’s Wonders.

Lovely piece Bill. Thanks for sharing.