Washington’s rivers, salmon and orcas need protection from Canadian mines

Good fences make good neighbors, wrote Robert Frost. Border walls aside, that remains true of Canadian mines upstream of Washington waters.

We love our Canadian neighbors and value much of what we share. But due to geologic fate, mining waste is something British Columbia may share in profusion with us in Washington, as well as Alaska, Idaho and Montana. It’s something we should worry about, and that Olympia must take action on.

Some of Washington’s greatest rivers begin in B.C., with big mines existing or proposed on the slopes above them. Last year, a notorious corporation applied to mine the unprotected “Donut Hole” in the Skagit headwaters, birthplace of Puget Sound’s largest river. Should a mine be developed and spill arsenic or other heavy metals, the toxic pollution would flow downstream into Washington, threatening salmon, orcas, fishermen, and local tribes and communities. These are unacceptable risks.

The Legislature recently held a hearing on Senate Joint Memorial 8014, which is intended to convey concerns to Victoria, B.C., cautioning against mining in the Skagit River headwaters. We thank the sponsors, Sens. John McCoy and Jesse Salomon, and support passage. We’re also grateful to Rep. Debra Lekanoff for her sponsorship of the companion House Bill 4013.

But this problem is not limited to the mighty Skagit. Major mines operate upstream of the Columbia, Kettle and other transboundary waters. The gorgeous Similkameen River drains through the Canadian side of the North Cascades, flowing into the Okanogan at Oroville. In its upper reaches near Princeton, a massive mine continues to produce toxic slurry. That slurry is held in a tailings pond behind an earthen dam hundreds of feet high, three times the size of the Mount Polley tailings pond that breached catastrophically in 2014, spilling more than a billion gallons of pollution into central B.C. salmon spawning habitat.

The company responsible, Imperial Metals, is the same outfit that wants to mine the Skagit River headwaters.

The company responsible, Imperial Metals, is the same outfit that wants to mine the Skagit River headwaters.

If waste from a Washington mine ended up in British Columbia, the liability would be covered because state law requires mines to post bonds sufficient to cover 100% of the cost of reclamation. B.C. has some requirements for financial assurances, but the province often does not require mine operators cover all the costs of cleanup. Government reports show there is at least a $1 billion gap in unfunded mining liabilities in B.C.

This isn’t an idle threat for Washingtonians, as a century of mercury pollution from a smelter near Trail, B.C., has so contaminated the Columbia River and Lake Roosevelt that cleanup will cost more than a billion dollars. Litigation to cover those costs has dragged on for decades due to the lack of regulation.

If mining corporations are required to post financial assurances upfront, not only will remediation and compensation occur more quickly after an accident, but the companies will be far more motivated to act responsibly and minimize the potential for disaster.

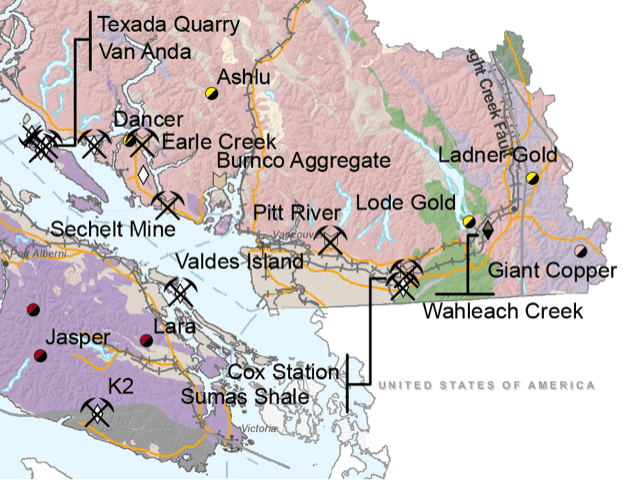

As many as 33 mines are either active or under exploration in B.C. within 60 miles of the Washington border. There are dozens more within a similar distance of Alaska, Idaho and Montana. Alaskans also are mobilized against the risk, including native tribes, local communities and fishermen, many of whom return to port in Seattle. Consequently, U.S. Sen. Lisa Murkowski, R-Alaska, recently led a bipartisan letter of concern to Canada signed by all eight senators from the four border states.

Tribal, fishing and conservation interests are now looking to Olympia to engage in defense of our healthy watersheds. We call on the Legislature to pass SJM 8014 and to take up and pass a broader memorial calling on Victoria to require financial assurances for all mines.

Gov. Jay Inslee and state lawmakers should do all they can to encourage B.C. to adopt the requirement that mine operators cover the costs of cleanup and otherwise update its Mines Act.

It’s only neighborly.

Take action using this form and learn more about Conservation Northwest’s Healthy Watersheds Campaign.

Jay Julius is a fisherman and former chairman of the Lummi Nation.

Pete Knutson is the owner of Loki Fish Company and director of the Puget Sound Harvester’s Association.

Mitch Friedman is the founder and executive director of Conservation Northwest, an organization working on behalf of wildlife and wildlands in Washington and British Columbia.

Top photo by Mt. Baker Experience; 2nd photo by Wilderness Committee.