Red Moons, Meteors and Mars! Oh My!

By Kaci Darsow

By one thirty in the morning, my beer was empty, my hands were numb and the dimly lit but distinctively red moon was sinking fast into the trees, making it difficult to view from my porch. Though the astronomical show would go until 2:30 am and Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon had only played halfway through, I decided to call it a night. The others had made that decision nearly an hour ago. Maybe I should try to get at least some sleep this week. Goodnight, strange moon.

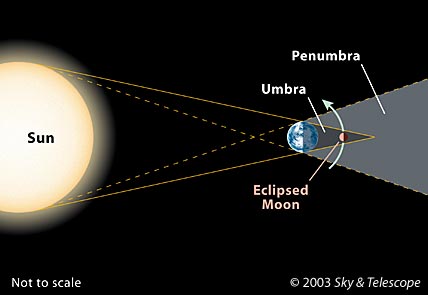

A full lunar eclipse is a wonderful production. First, the penumbra casts darkness across the face of the full bright moon. Within an hour, before your eyes the moon wanes from full to crescent. Then the umbra creeps in, staining the moon red. Paradoxically, this vibrant hue occurs while the moon is in the deepest part of Earth’s shadow. Light from the sun is refracted around the Earth through the atmosphere. The longest rays of visible light, which our eyes register as red, illuminate the moon in a mesmerizing shade of rust. Once again the penumbra slides across the moon, darkening the deep red and making it difficult to see. Eventually, the Earth’s shadow will move on, revealing a waxing crescent of bright yellow. Then, like a time-elapsed film, two weeks of moon phases will wax back to a full silvery orb in an hour. The whole show takes just under four hours.

If you missed Monday night’s performance, don’t worry. The entire process will happen again on October 8, 2014, and then twice more in 2015. You’ll have a total of three chances between now and September of next year to catch it.

How the full lunar eclipse works. Illustration by Greg Dindermann, courtesy of Sky and Telescope.

Full lunar eclipses are rare. The last once occurred in December of 2011. The elliptical planar orbit of the Earth must line up precisely with the position of the moon, and this must happen during a full moon in order for the full lunar eclipse to occur. These things must align on a clear night, making Pacific Northwest full lunar eclipses especially rare.

The night started very cloudy. There had been talk of midnight lunar-eclipse canoeing, but by 9:30 any plans for a late night paddle had been scrapped. Most folks surrendered to sleep, defeated by the promise of no visibility. But ten minutes into the show, the cloud curtain opened to share the performance. Just shy of midnight, I politely knocked on windows and doors, inviting a few night-owl friends to join me in watching the celestial spectacle. Everyone who had a light on got a knock.

Five nature nerds ventured into the cold, gusty night to stand and stare and wonder. As I watched the moon wane away before my eyes, I felt I simultaneously understood the moon as an object in space while also being completely baffled by it. It is depictions of scientific principles such as these that are both clear and exciting, but that I often struggle to explain. Scale makes it difficult to comprehend the position and movement of the sun, the moon and the Earth, but watching the lunar eclipse gave me a solid sense of those relationships. Watching the moon disappear was a bit unsettling, however. The time elapsed movie of moon phases did not compute in the contexts of sky with a background of stars. It was all very perplexing. It didn’t seem real. I felt like I could just pick it right out of the sky, like a rock off the beach. My brain kept trying to “fix” what I was seeing, filling back in the disappearing parts of the moon, later trying to blink away the strange hue that began to filter over the moon.

As we stood in the middle of the night, gazing into space, we tried to describe what we were seeing. First, came the naturalist jargon. Words like refraction, waxing and waning moon phases, planar orbit and umbra were tossed around with ease. But as the sight of the moon became more bizarre, our descriptions became more imaginative.

“Whoa, it looks like a huge floating eye. See the cornea and all the blood vessels?”

“The Eye of Sauron.”

“It looks like a cheese puff!”

“It looks like a giant popcorn kernel waiting to be popped!”

“The color is more like popcorn covered in nutritional yeast.”

“No, it’s darker than that.”

“Popcorn with nutritional yeast and Braggs?”

“Yeah, that’s it! It’s definitely the color of ultimate hippie popcorn.”

“You guys, the moon totally is the ultimate hippie popcorn.”

Although we had all gotten out of bed, taken a break from last minute taxes or put aside homework to come out and watch the eclipse, the moon was far from the only celestial body on display. A bright red object shone in the sky above and to the right of the moon. Could it be Mars? It almost seemed to big and bright to be our neighboring planet, but it certainly was not a star. None of us knew for sure. A quick Internet search revealed that we were not only right about this mysterious orb being the red planet, we were also inadvertently observing Mars from the nearest view we get from Earth: “at opposition”. This means the Earth is about to reach its farthest distance from the sun, while Mars is about to reach its closest, bringing our planets within 57 million miles of each other.

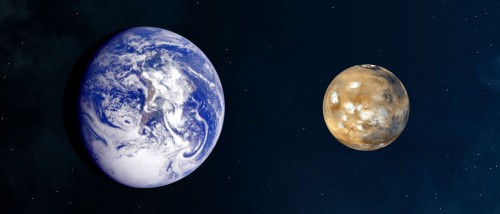

From L to R: Our home, the Earth, compared to our neighboring planet, Mars. Photo courtesy of NASA.

So there we were, mesmerized by the moon’s best Mars impression, while the actual Mars was slowly creeping closer and closer, when suddenly…

ZOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOMM!

One of the longest lasting meteors I’ve ever seen streaked across the sky, right down the middle of the whole scene. I mean, this meteor was so bright and lasted long enough for us to jump up and down, pointing and shouting, “Look! Look! A meteor,” before it dove below the horizon. The next time you see a shooting star, try getting six syllables out before its gone, and you’ll get a sense of just how epic this meteor was. More research revealed that mind-blowing meteor was a precursor to an annual meteor shower called the Lyrids. This shower will begin April 17th and intensify over the next few days, peaking on the 22nd (Earth Day!) when the rate of meteors will be around a dozen an hour. Look to the eastern sky in the predawn hours for your best chance to catch the show.

Red moons, meteors and Mars. All such celestial happenings are reminders for us Earthlings to look up, go outside in the night and stay out past our bedtimes every once in awhile. That we are not just part of the Earth — fight for and use it as we may — but of the entire unfathomable Cosmos. Lucky aliens, zooming through space. I’ll see you on the dark side of the moon. Cheers!

Now’s the time, the time is now! Stay up late, go outside, look up, have your mind blown! Photo courtesy of Logan Brumm Photography.

Now’s the time, the time is now! Stay up late, go outside, look up, have your mind blown! Photo courtesy of Logan Brumm Photography.

Leading photo: The “blood moon”. This is what a total lunar eclipse looks like. Catch the next on on October 8, 2014. Photo by Richard Tresch Fienberg, courtesy of Sky and Telescope.

Kaci Darsow is a graduate student in North Cascades Institute and Western Washington University’s M.Ed. program. Most nights Kaci can be found on their porch enjoying a good porter or stout and listening to Dark Side of the Moon, regardless of lunar activity.

Kaci – great Chattermarks post! There was no moon to be seen in Bellingham… it must have hung over Diablo Lake for the entire night.