A Neverending Cascade of Snow

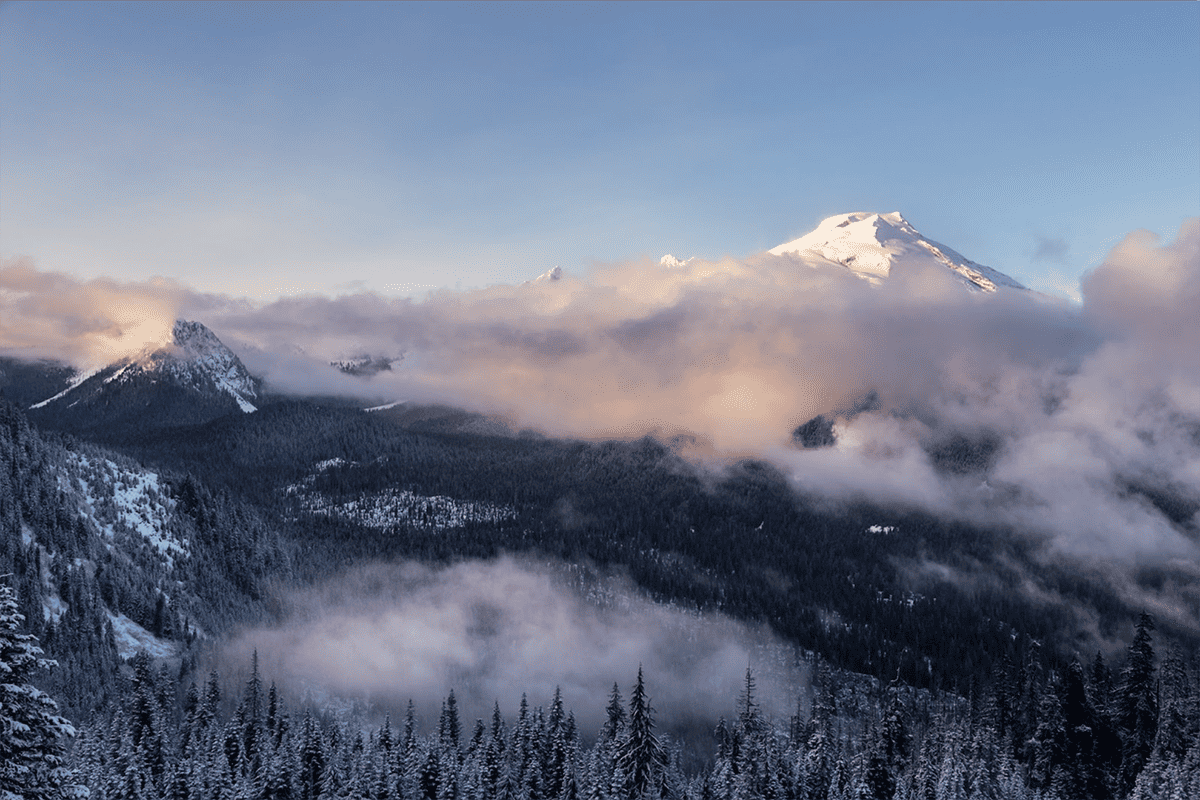

As the days shorten and cool mornings frost over the memories of a hot, dry summer, Washington’s reservoir begins to grow in the mountains. Most years the first refresh arrives sometime in September as the early autumn storms regreen the landscape. Majestic old-growth forests exhale sighs of relief, reopening their stomata as moisture permeates the dusty soil. In the subalpine meadows, fat raindrops strike the vibrant red groundcover causing the blueberries to quiver, shaking off their matte coating. As elevation increases and the plant life fades, the rain continues its transition, first into a frigid slurry of ice and water sluicing through the air, and then into delicate ice crystals which drift down, collecting on only the highest, rockiest summits–the first winter snow cap.

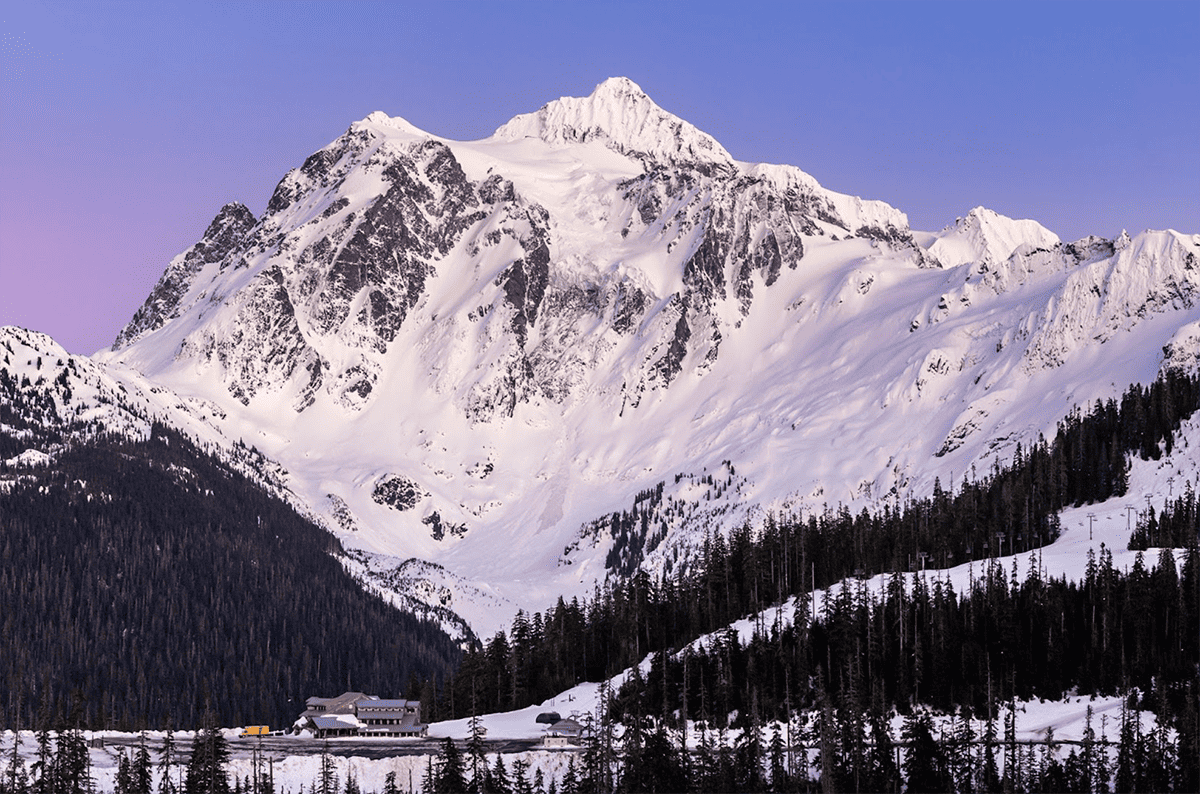

This cycle repeats with greater frequency and extent as the landscape goes through its fall fashion show and transitions to monochromatic winter tones. With each storm the snow level drops and more of the peaks are clad in their wintery white. The cold season snow cycle occurs throughout the northern latitudes, but almost nowhere is it more spectacular than in the North Cascades. As the season progresses, the winter coat builds across the high elevations, first covering the rocks and bushes and trails, then submerging the smaller trees, and eventually leveling even the most rugged terrain.

For a city, a ten inch (25 cm) snowstorm ranges from disruptive to debilitating. Public transport shuts down, schools and offices close, and travel can become impossible. For the North Cascades, this is an ordinary winter Tuesday. Here, in one of the snowiest locations in the world, it’s not uncommon to receive 250-300” (~7 m) of snow in a month. During the 1998-99 winter the Mount Baker Ski Area set a world record for snowfall measured in a single season as it was buried under 1,140” (95 ft or almost 29 m) of snow! Incredibly, almost all of that fell over a five month period from Nov-Mar averaging more than 7” (20 cm) a day (Leffler et al., 1998).

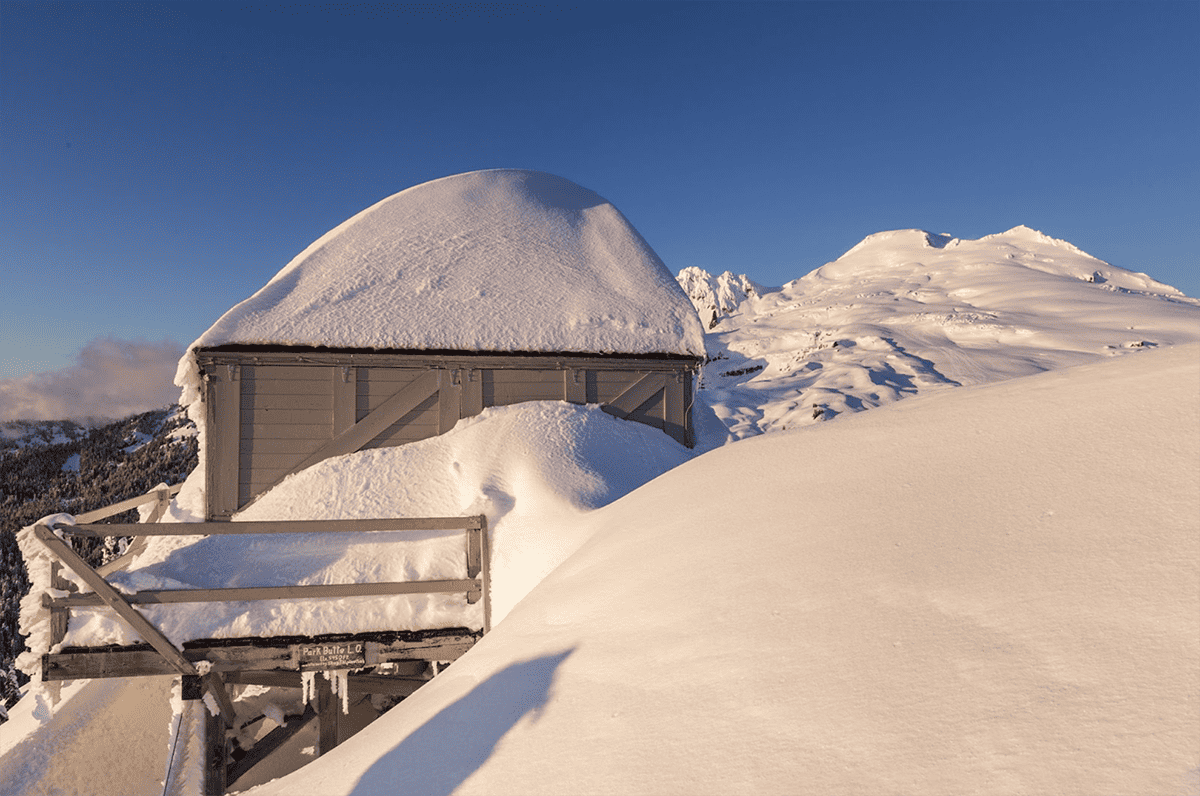

Visiting the North Cascades at any time of year hints at the enormous quantities of snow that falls throughout the range. During the stormy fall, winter, and spring, storm after storm after storm batter the North Cascades dropping feet of snow. The snow clings to everything. Trees, rock faces, buildings, and roads are all smothered under the endless storm of ice crystals. This abundance of snowfall can continue even into the late spring when the weather of Memorial Day may give off December vibes. In the summer, when the skies clear and temperatures pop up near 80°F, the everlasting snow remains, slowly releasing its glacial lifeblood to the watershed below.

The North Cascades receive excessive quantities of snow due to a number of factors. Partly it’s the proximity of high terrain to the ocean. Large bodies of water can essentially supercharge the atmosphere, leading to enormous floating rivers of moisture that stream across the ocean. When these atmospheric rivers approach mountains, the terrain forces them upwards, wringing out the precipitation. Many places in the Cascades pick up 100-200” of precipitation a year, most of that falling as snow in the cooler months.

The North Cascades are also located at a perfect latitude to receive the brunt of winter storms. During the winter the jet stream (the main conveyor belt of storms) moves southward and from November-February sets up over the Pacific Northwest. Storm after storm pummels the region and while it falls as rain near sea level, the snow level hangs around 3-4,000’ (~1,000 m) which means the high terrain is buried in snow. Additionally, the somewhat southern latitude of the Cascades means they can tap into a warm moisture-laden atmosphere to maximize their snow totals. Many of the coldest places in the world (like Antarctica) are deserts with cold, but dry air and see significantly less snow than the Cascades.

While Mt. Baker Ski Area’s annual snowfall record of 1,140” still stands as a world record, during that season nearby areas likely picked up significantly more snowfall. In the summer of 1999, Glaciologist Dr. Mauri Pelto, who for 40 years has run the North Cascades Glacier Climate Project, estimated accumulation totals near 2,000” (50 meters) on the higher slopes of Mt. Baker (Pelto 2000). Unfortunately, the fundamental challenge of identifying the snowiest places in the world is that the locations are extremely challenging to research for much of the year due to their isolation and the intensity of conditions.

One way to study snowfall after it has fallen is to measure the seasonally accumulated snow depth on glaciers. By measuring the snow height of each annual layer (differentiated by characteristic seasonal melt patterns) scientists can estimate the mass of snow (or more accurately mass of water equivalent) that falls each season on a glacier. From there they work backwards to estimate the total seasonal snowfall. A 1999 study from the Southern Patagonian Ice Field in Southern Chile found an area accumulating upwards of 5,000” (130 m) of snow a year (Rasmussen et al., 2007)! Imagine more than a foot of snow falling every single day of the year! There are similar snowfall estimates up in the Fairweather Range of southern Alaska. There, in the tallest coastal mountains in the world, the snow comes down almost continuously.

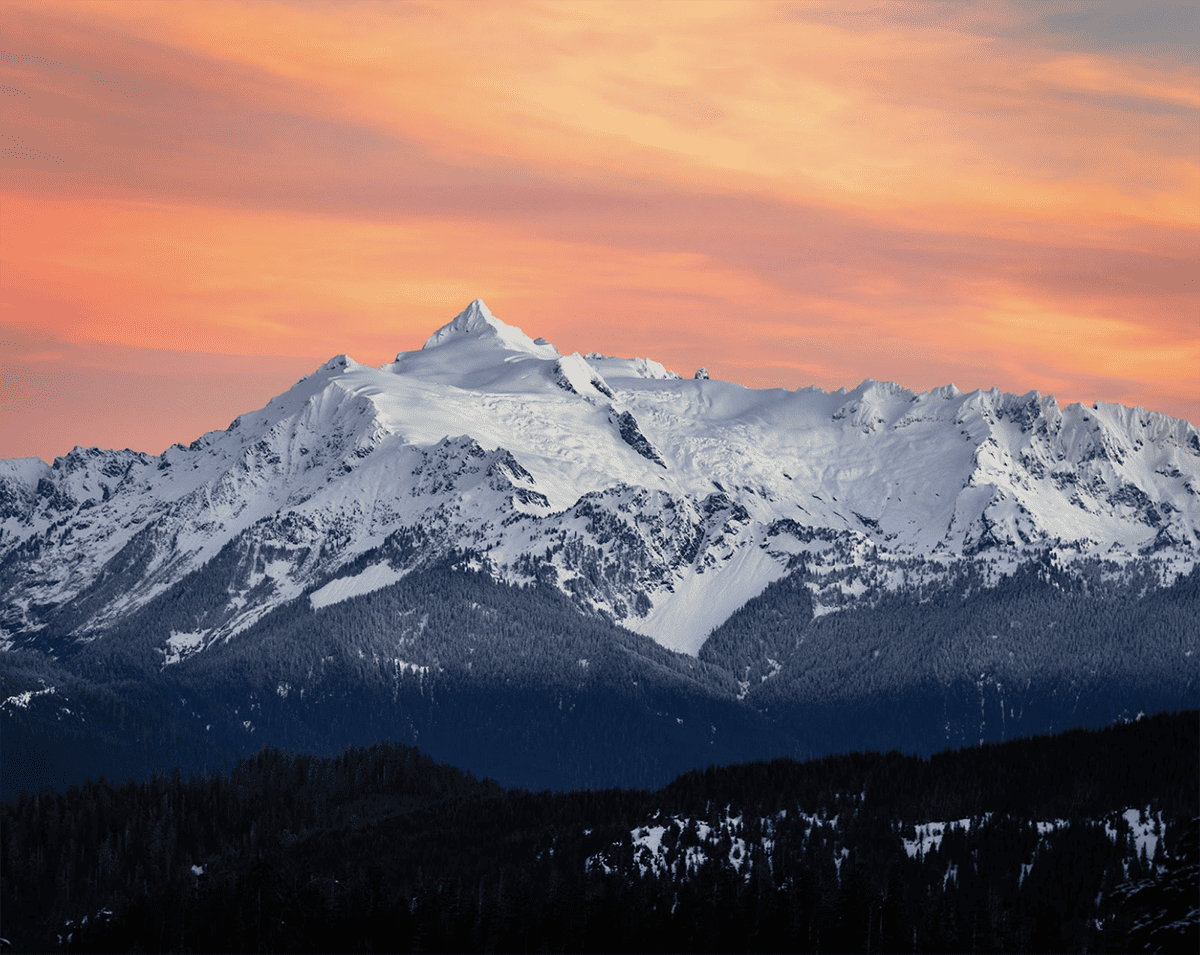

But for now, the North Cascades retains their snowfall record. These rugged peaks pick up 1,000”+ of snow a year and feature glaciers that survive below the elevation of major US cities. And despite 2023 being an El Niño year which generally correlates with warmer temperatures and lower snow totals, the North Cascades will still likely see more snowflakes than anywhere else this winter.

About the Author

Wyatt Mullen is a Skagit based landscape photographer and science communicator interested in the impacts of climate and weather on the North Cascades region. He has spent much of the last three decades exploring the trails, forests, glaciers, and mountain summits of the North Cascades and in 2023 worked with the Institute as a program instructor. His work can be found on wyattmullen.com or through daily science based posts on Instagram: @wyatt.mullen.

Sources

Leffler, Robert J., et al. “Evaluation of a National Seasonal Snowfall Record at the Mount Baker, Washington, Ski Area”. National Weather Digest, 1998, pp. 15–20

Pelto, Mauri S. Summer Snowpack Variations with Altitude on Mount Baker , A Comparison with Record 1998 / 1999 Snowfall. 2000.

Rasmussen, L. A., et al. “Influence of upper air conditions on the Patagonia icefields”. Global and Planetary Change, vol. 59, no 1–4, 2007, pp. 203–16, doi:10.1016/j.gloplacha.2006.11.025.