Submarine Parents: How Orcas use Social Strategy in Parenting

Connecting to the natural world was tough when I was younger. I was taught

that understanding the natural world was the domain of a scientist, and that there is a right and a wrong way to do science. Science took the natural world out of my hands and set it on a shelf high out of my reach. However, the TV remote never seemed out of reach.

To this day I still have a deep love for cartoons. The simple artistic medium

allows us to give personality and emotion to even the inanimate. So when I had

the chance to get to study our natural world through the North Cascades Institute I knew I had to get drawing. I decided to study three social animals, The Beaver (Castor canadensis), the Raven (Corvus corax), and the Orca (Orcinus orca). All of them were tons of fun to sketch, but what really drew me in was the story of the Orcas.

In the Salish Sea lives an ecotype of Orcas referred to as the Southern

Residents. Three large groups of killer whales spending their days swimming

through the San Juan Islands looking for their favorite food: Chinook Salmon.

These wonderful creatures care for each other so much it warms my heart. They

are known to share food, baby sit each other’s children, and adopt one another

into their tight knit families should unfortunate circumstances leave one of them alone. In this way, parenting becomes a very social act for the Southern

Residents.

There is an Orca named Tahlequah who gave birth in the summer of 2018. Her calf did not survive for even an hour, sadly, but Tahlequah couldn’t let go. She carried her dead calf for 17 days. It is important to understand that killer whales don’t stop swimming, even to sleep. For a very long time Tahlequah carried that calf, not stopping to eat or rest. It was unprecedented. As the calf began to decompose she carried it, still.

It would be extremely surprising for one animal to mistake this child as being

alive, and it would be nearly impossible for Tahlequah’s whole pod of Orcas to not know the difference. And yet other members of the pod took turns carrying the dead calf so that she could rest and eat. They gained nothing out of carrying this burden, but they did it anyway. How could this be anything else but a show of grief and of pity? We may never know if animals experience emotions as we do, but after my studies I know what my beliefs are.

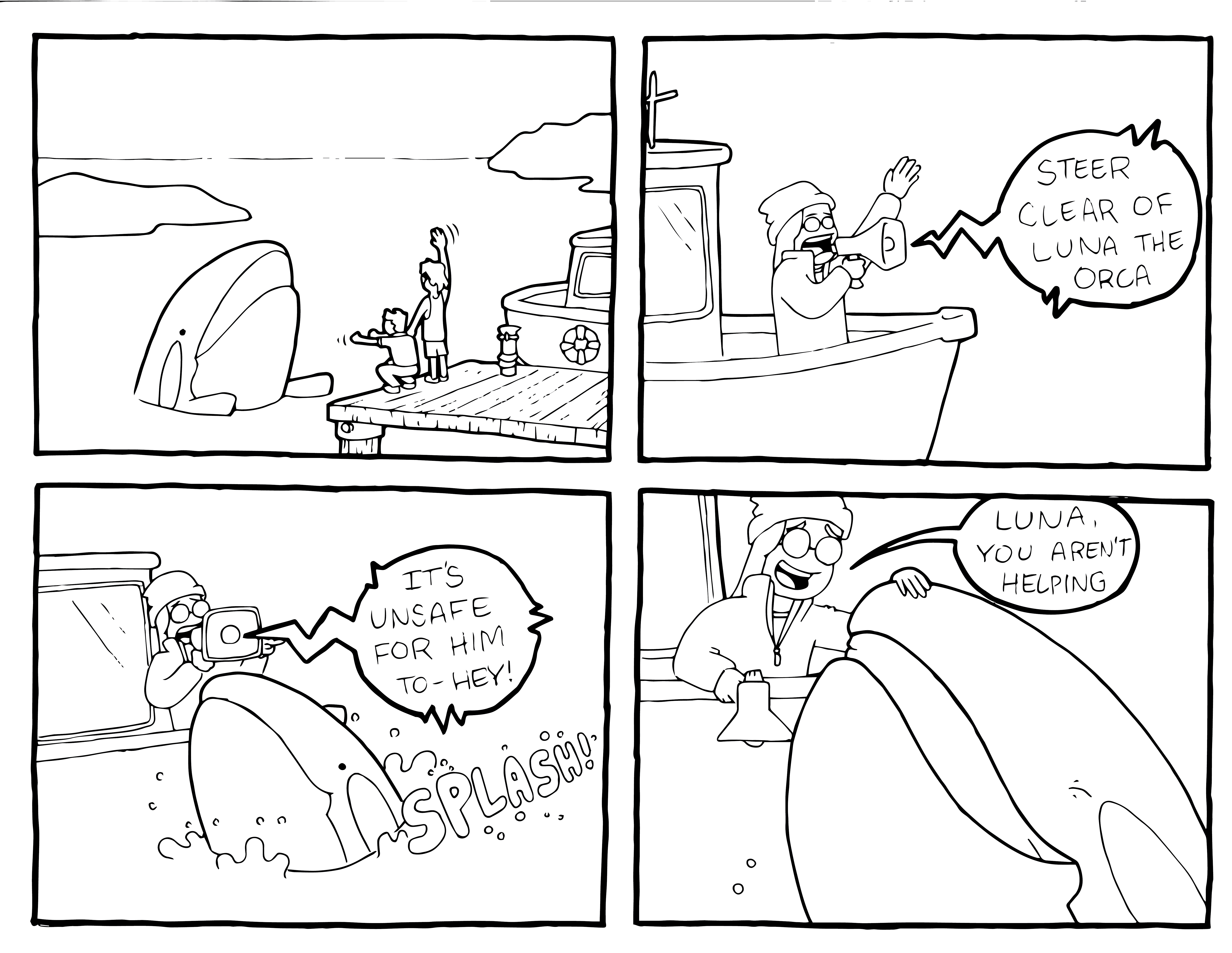

Emotions, or not, the killer whales have a very deep need for social interaction. Luna, was a Southern Resident who was separated from his family early in his life. He spent five years in the Nootka Sound in Canada building social bonds with the human lives, and boats, he met. Many organizations argued about the appropriate response to this separated whale was. Some organizations like the DFO (Department of Fishery and Oceans) took to warning other boats not to interact with Luna, fearing he might become too comfortable around the dangerous vessels. However, the DFO vessels were just another friend to the gregarious Luna.

Unfortunately the fate of these social animals is unclear today. The health of their community dwindles with the numbers of available salmon in their waters. Their habitat and primary food source suffering greatly from human impact, we can’t be sure what is in store for their future.

This post was researched and written by Thumper Ormerodfor the Northwest Natural History course as part of the Institute’s Graduate M.Ed. program. North

Cascades Institute has not extensively fact-checked the information contained herein and recommends researching other sources of information to enhance one’s understanding of the topic.

Check out the work that these organizations and state agencies are doing to improve the health and sustainability of the Southern Resident Orcas and find out how you can get involved.

Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife

Washington State Governor’s Office

Washington Department of Ecology