The Field Journal of a Naturalist: Grinnell Journaling in the North Cascades

This Naturalist Note is written by graduate student Nate Trachte, as part of the Fall Natural History Project In North Cascades Institute’s M.Ed. Residency coursework. You can view more students’ work here.

When in the midst of a long-term project it is all too easy to lose sight of the purpose, or downplay the importance of the seemingly ordinary tasks at hand. Many times while keeping my naturalist field journal, I felt as though what I was doing was trivial. Then something would pique my interest and the words of wiser people than myself would pop into my mind. What does it mean to maintain a field journal? Why bother?

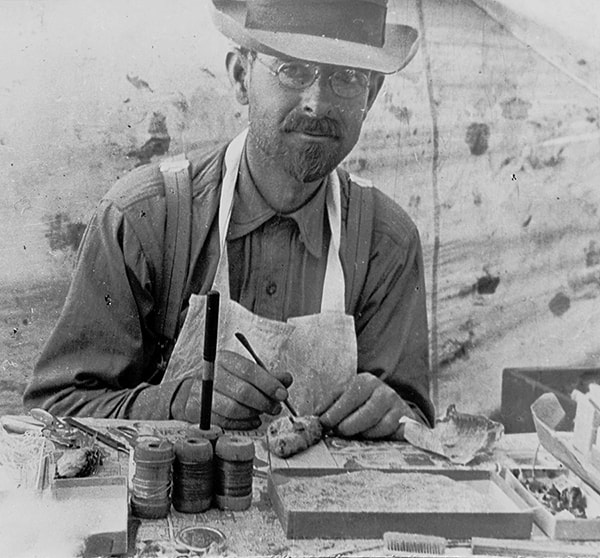

Although he never lost sight of the potential magnitude of his work, Joseph Grinnell — the “father of field notes” — would not be recognized until much time has passed. The brilliance of his 3005 page, 30-year-plus, documentation of California’s flora and fauna in the early 1900’s is now finally being valued. Grinnell, however, knew the potential value of his naturalist party’s work all along. In 1908 he noted,

Our field-records will be perhaps the most valuable of all our results. …any and all (as many as you have time to record) items are liable to be just what will provide the information wanted. You can’t tell in advance which observations will prove valuable. Do record them all!”

He knew that by being consistent and thorough, his field notes would not only be taken seriously but also be of value to researchers in the future.

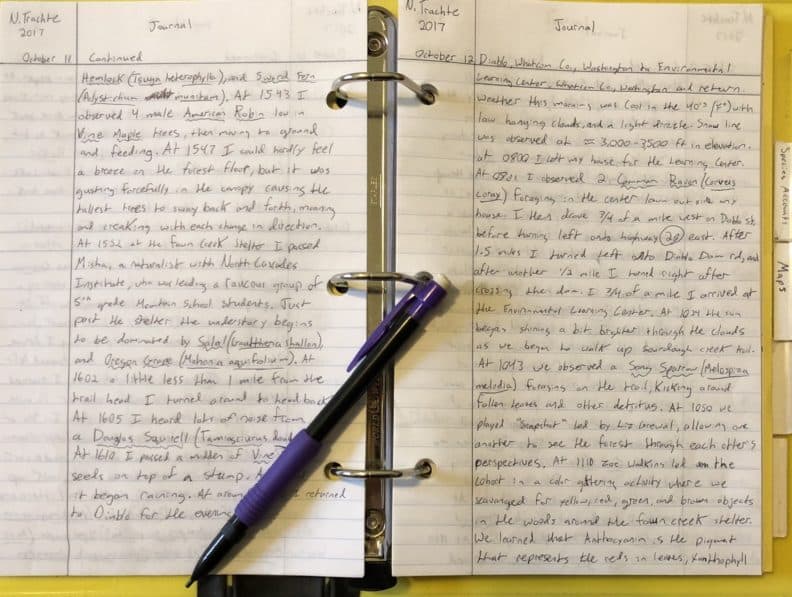

The style of the Grinnell Journal is a meticulous, requiring time and attention to detail. In order to be true to the style it requires certain materials; specific paper, a binder, a right angle to format with, and many field guides for the layman. The time that goes into formatting each page, looking up scientific names, and telling the story of the day is daunting. Each entry needs to contain the following:

- location and route for the day

- weather observations

- landscape features

- and documentation of species observed.

For the month of October, I kept a field journal inspired by the style of Joseph Grinnell. Why take the time to do such a ridiculous thing? In an attempt to notice more patterns in the natural world, pay attention to the things going on around me, and learn more bird species obviously!

I realized through this journey that recording these naturalist observations is important, if not for science, at the very least for those who will come after myself. In the Stehekin Valley I once watched as an elderly man read journal entries from a woman whom he was a descendant of. These simple entries came from a time when the family was homesteading in the area. I saw in his eyes that these daily accounts were of boundless importance to him.

Throughout the month I was able to identify 24 species of birds, many of which were new to me. I had a journal of 60+ pages of writing accounting my fall days in the North Cascades. I wrote down as much as a could, inspired by the idea that even if I do not think it is important that someone in the future might. I lived the motto of no Grinnell tonight, no oatmeal tomorrow.

~ Nate Trachte