Wolves in the Land of Salmon: David Moskowitz tracks canis lupus’ return to the Northwest

Vargas Island wolves at Clayoquot Sound, BC; photo by David Moskowitz.

David Moskowitz presents his new book Wolves in the Land of Salmon at Village Books in Bellingham on March 21 and at the North Cascades Environmental Learning Center on March 23-24, where he is also leading a tracking class in the Upper Skagit Valley.

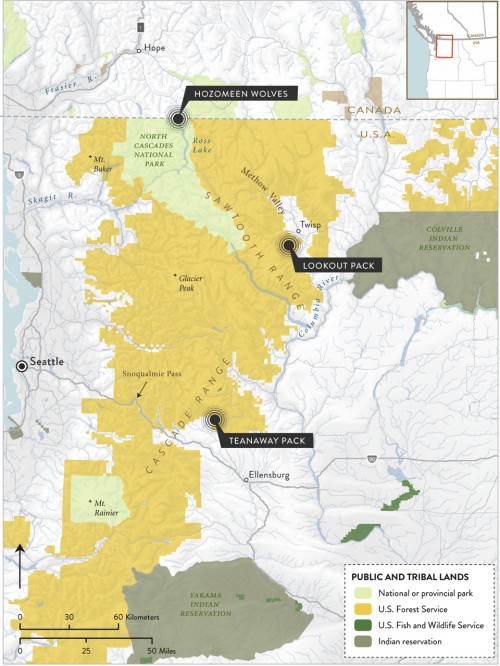

Reports of gray wolves moving back in to Washington State have been scattered in local media over the past several years: sightings here, tracks there, poaching in the Methow, a state-run hunt in the far northeastern corner. We’ve seen Conservation Northwest’s stunning remote-camera photographs of the Lookout Pack and people have heard their distinctive howls from Hozomeen to Teanaway, less than 100 miles east of Seattle. Their sudden reappearance and rapid distribution have taken many by surprise, with developments happening so quickly it’s been a challenge to keep up with the latest news.

Map created by Analisa Fenix/Ecotrust under a Creative Commons license and prepared for publication by Laken Wright.

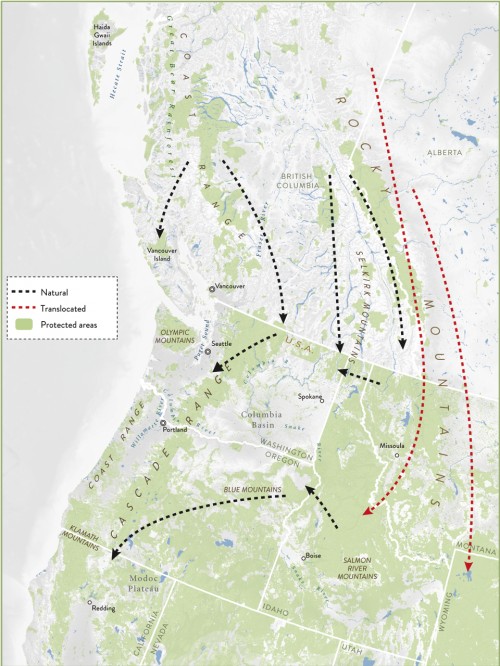

Map created by Analisa Fenix/Ecotrust under a Creative Commons license and prepared for publication by Laken Wright.

Enter Wolves in the Land of Salmon by Carnation-based naturalist, author and educator David Moskowitz. In his new book from Timber Press, he pulls together the many strands of wolf recovery in the Pacific Northwest—natural history and biology, politics, landscapes, the array of opportunities and challenges—in to a invaluable compendium of up-to-date information, written in an exceedingly straightforward, scientific and balanced way.

Moskowitz, a trained tracker sensitive to reading signs on the land, takes the reader on a journey from the perspective of the wolf, and his writing is greatly informed by on-the-ground experiences as he seeks to better understand our new packs across varied regions including the North Cascades, Blue Mountains, Selkirks and Columbia Highlands, Vancouver Island and the Coastal Range in British Columbia

Map created by Analisa Fenix/Ecotrust under a Creative Commons license and prepared for publication by Laken Wright.

One striking aspect of his investigation is how each pack of wolves fits in to these discrete ecosystems in different ways, adapting to terrain, human interference and the available prey base in variations that Moskowitz expertly teases out.

Christian Martin: Why have wolves “suddenly” appeared in so many areas across Washington State?

David Moskowitz: Wolf populations can grow quite quickly once they establish a foothold in a landscape. They have a high reproductive rate for a large carnivore. Young adults will either disperse to adjacent areas to where they were born or they may travel several hundred miles before settling down.

CM: Are there benefits to Washington wolves repopulating naturally as opposed to translocation?

DM: Allowing wolves to naturally repopulate in the state is less expensive and less likely to trigger people who are suspicious of the government and its intentions related to managing landscapes. Also, some evidence suggests that wolves tend to disperse into landscapes ecologically similar to where they were born, perhaps giving them a leg up on surviving in their new home compared to wolves from an ecologically different origin.

CM: What are some of the differences between wolves most people are used to hearing about in the Rocky Mountains versus the ones repopulating Washington from coastal British Columbia?

DM: There is far more similar than different between wolves across the Pacific Northwest. However, coastal wolves are currently classified as a different subspecies than the wolves that occupy the interior of our region.

Wolf on Meares Island; photo by Moskowitz.

Ecologically, they have adapted to the unique coastal rainforest habitat. This shows up in their behavior—traveling along shorelines and swimming between islands extensively. It also shows up in their diet. In some packs, salmon and animals harvested in the intertidal zone make up the majority of their diet at certain times of the year, compared to in the Rockies where deer, elk, or moose are almost always the primary food source.

CM: Where are the most ideal regions in the state to accept new wolf packs?

DM: Washington’s southern Cascades are probably the best chunk of available wolf habitat in the state that wolves will likely occupy relatively soon. The Olympics also have lots of good habitat but it may be many years before a breeding population of wolves naturally establish themselves there.

CM: Why, and should we assist them in getting out there?

DM: The most likely route for wolves to naturally disperse to the Olympics is from the southern Washington Cascades and it will be sometime before this area has a breeding population its self. On top of this, between the Cascades and the Olympics is a lot of human development and poor habitat for wolves. This will slow the rate of natural dispersal into the Olympics. At least one study suggests that the land between the southern Cascades and Olympics is the most compromised of all of Washington’s large carnivore wildlife corridors.

While relocating wolves from other parts of the state to the Olympics could theoretically hasten this process, actually achieving this task would be exceptionally costly both economically and politically. In the Northern Rockies, one of the largest complaints from many people about the return of wolves was the role of the government in translocating animals. Here in Washington, all of our wolves have naturally dispersed into the various places they now reside in the state, a fact that, for some, makes their presence on the landscape more tolerable. Human tolerance of wolves is at least as important a facet of conservation of the species as is dealing with impaired wildlife corridors.

Photo by Moskowitz.

CM: What are some of the benefits to our local ecosystems in having wolves back in the web?

DM: How wolves alter ecosystem dynamics in the state will really depend on how we manage wolves, including how many wolves we allow to persist and where we accept their presence.

Their influence on the behavior and population of game animals such as deer and elk is the biggest way that they influence ecosystem dynamics. Large ungulates can significantly deteriorate many aspects of a landscape in large numbers overtime without predators. A recovered population of wolves, paired with the presence of other large carnivores, can shift how prey species use the landscape, change population sizes of prey species and change the foraging behavior of prey species.

These changes in turn affect how herbivores impact plant communities, potentially allowing trees and shrubs in sensitive habitats to rebound. Increases in tree saplings and shrubs that have been suppressed by heavy browsing pressure from ungulates can lead to increased habitat value for a wide variety of other wildlife species such as birds and beavers. Of course changes in these species of wildlife can in turn cause more ecological ripples across an ecosystem.

The relationship between large predators and herbivores and the impacts of removal of predators from ecosystems has been studied around the world. However, we are still learning a great deal about how the return of large carnivores to landscapes affects the ecology of those area and I am sure we will learn a great deal about this process from the recovery of wolves right here in the Pacific Northwest.

One thing is certainly true though, wolves are a highly interactive species and when they are present on a landscape many other species, including humans, take note and adapt to the presence of wolves. Coyote populations often decrease and shift their habitat use, grizzly bears enjoy a new food source (the remains of the large animals wolves kill), humans change their livestock guarding practices, elk become more vigilant and avoid areas of high risk of attack from wolves. Each of these changes can spur secondary changes in the landscape caused by plants and animals that are in turn responding to shifts of the animals who have directly responded to the presence of wolves.

CM: What do you see as the biggest obstacles to wolf recovery in Washington?

DM: Balancing the needs of humans with the needs of this wide-ranging, large animal and balancing the desires of various elements of our society which value wolves on the landscape in different ways.

Photo by Moskowitz.

CM: What do you mean?

I mean the biggest obstacles to wolf recovery are deciding as a society how we wish to accommodate wolves in the state. Humans extirpated wolves from the state very intentionally in the 20th century. The only reason they have now returned is because our society as a whole has decided to tolerate their presence again. We are a very diverse society however, and people in the state have a wide variety of perspectives about this topic. Finding a path for wolf management that reflects the will of the majority, while at the same time respecting the perspectives of segments of society which are concerned about how wolves will affect them will be a continual challenge.

The reality is that, on some level, wolves and humans are biological competitors—we both have a taste for hoofed mammals. In nature, there are almost always conflicts between two species that compete for similar resources. On the other hand, humans are a very complicated species and, while some of us see wolves as competition for vital resources, others see wolves as an integral part of a healthy functioning ecosystem which provides other vital resources like clean water, clean air, biodiversity. It is also equally predictable that if a species benefits from the presence of another species, the first may act quite benignly towards the second.

There are examples of this sort of behavior in how wolves themselves deal with their wild neighbors, for instance killing and harassing coyotes whom they see as competitors. Our challenge, as a highly social species, is to manage these competing interests from within our own ranks. This is true not only in how we manage wolves but in how we relate to all aspects of our habitat—from the local forests and parks we recreate in to the Earth’s atmosphere. Whether its debating whether or not to compensate ranchers for lost livestock from wolves, or whether or not to increase fuel efficiency standards for vehicles to deal with greenhouse gases, we are dealing with symptoms of a social conflict within us as a species. Ultimate solutions will require a way forward that accommodate the needs and values of all segments of our society and this is a far harder thing to do then put up a fence to keep wolves away from sheep at night.

CM: Do you think that Washington State’s wolf plan is scientifically sound and taking wolf recovery in the right direction? Is there anything you would change about it based on your experiences studying and tracking Washington’s wolves?

DM: Washington’s Wolf Management Plan is probably the most progressive and scientifically and socially well thought-out management plan of any western state currently. If the state follows the guidelines for managing wolves in the state set out in this plan, wolf populations will almost certainly recover across much of the state. That being said, compromises in the plan which made it more acceptable to those concerned about the negative impacts of wolves on livestock and hunting opportunities means that wolves may not be recovered in the Olympics before they are removed from endangered or threatened status by the state.

Ultimately, I think the states plan does a good job of attending to the variety of needs and interests of the people of the state. The biggest challenge now is to fairly implement the plan. If we do, it is very likely wolves will recover in the state, there will still be a huge livestock industry in the state, and people will still have ample deer and elk hunting opportunities.

Black bear skull found on Ross Lake close to wolf tracks; photo by Moskowitz.

Black bear skull found on Ross Lake close to wolf tracks; photo by Moskowitz.

Maps and images taken from Wolves in the Land of Salmon © 2013 by David Moskowitz. Published by Timber Press, Portland, OR. Used by permission of the publisher. All rights reserved.