Bumblebees: An Essential Spring Harbinger

One of the most iconic harbingers of spring is the sound and sight of the gentle queen bumble bee. When she emerges in early Spring, she has spent the Winter in diapause (insect hibernation) waiting for the warmer temperatures of to begin a new generation of bumble bees. Her first few days are spent collecting pollen and nectar so she can replenish her energy and find a suitable nest site to begin a new colony. In the next couple of weeks she will begin to lay eggs while continuing to collect pollen and nectar for herself and her developing larvae. The larvae will pupate and emerge as the first generation of female bumble bees. These will immediately begin collecting nectar and pollen and care for the second and subsequent generations. The queen will remain in the nest laying eggs throughout the Summer and Early Fall.

Bumble bees produce annual social nests in existing cavities such as abandoned rodent holes, under grass tussocks, rocks, and woodpiles. A colony can contain as few as 50 individuals or as many as 1,000, but between 50 to 250 individuals is more common. Bumble bees are among the first bees to emerge in Spring and the last to be seen in early Fall. Dr. Gretchen Bruhn summarizes bumble bee activity very succinctly in her book, Field Guide to the Common Bees of California: “Queen bumble bees fly in Spring, female workers fly in Spring, Summer and Fall, and new queens and males fly and mate in late Summer and Fall.” Bumble bees are found mainly in temperate climates but are also very important pollinators in alpine and arctic ecosystems.

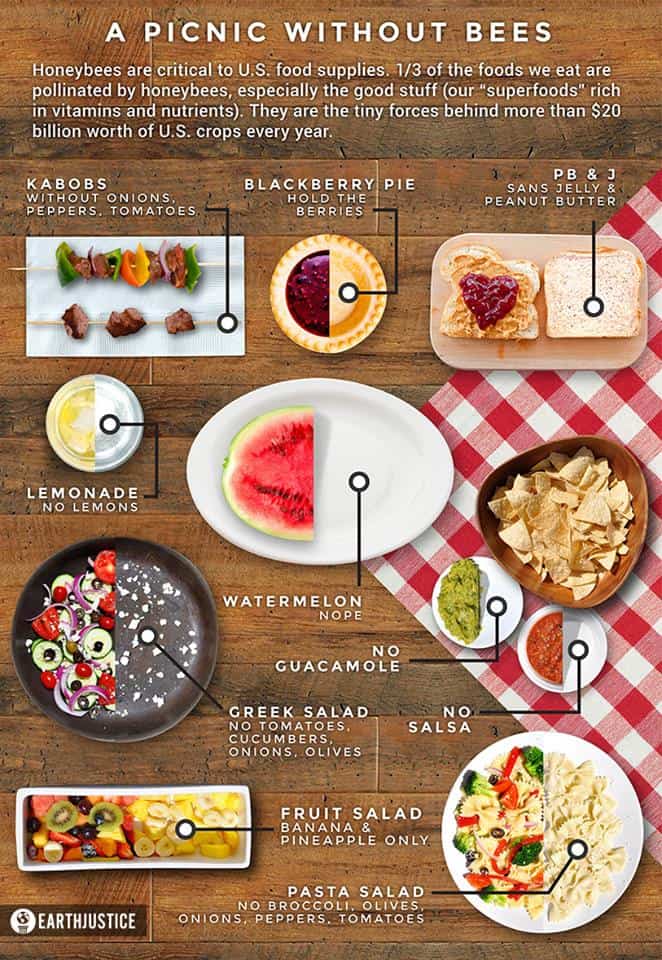

In the Spring I encourage people to observe bumble bees from a distance. The queen doesn’t need extra disturbances. She has important work to do. By providing pollen and nectar for herself and her first generation female larvae, she is also pollinating plants so they can reproduce and thrive. These plants add healthy nutritional diversity to most organisms’ diets, including ours. Imagine how limited your diet would be without pollinators. Check out the A Picnic Without Bees graphic below and for a list of important foods in our diet requiring pollinators check out the Xerces Society and Friends of the Earth.

In the late 1990’s bee systematist (an entomologist who identifies and seeks to determine the evolutionary relationship of bees) began to document declines in the populations and distribution of bumble bees. Some of these declining bumble bee species were the most common species found in the United States. A number of factors are implicated in this drop. They include:

- Habitat Modification and Loss

- Pesticide Use

- Invasive Species

- Climate Change

- Diseases

Some diseases may have been introduced into wild populations of bumble bees when commercially reared bumble bees used to pollinate greenhouse plants, especially tomatoes, escaped to spread these diseases to wild populations. Two declining California species are on the Xerces Society’s Red List of Bees: The Franklin’s Bumblebee (Bombus franklini) is listed as critically imperiled and the Western Bumblebee (Bombus occidentalis) is listed as imperiled and its population is in sharp decline. These two species were also being reared for commercial pollination.

Presently, entomologist have identified over 600 species of native bees in Washington, and included in that total are 25 species of bumble bees. We don’t know what the populations of solitary and semi-social native bees are for sure because we have no baseline information to determine if their populations are declining, expanding, or stable.

What can we do to help conserve bumble bee diversity and their populations?

- Reduce or avoid using pesticides. Insecticides may kill bees outright or change their behavior and ability to forage for pollen and nectar and return to the hive or nest. Herbicides reduce pollen and nectar sources for bees. Some fungicides and antibiotics are implicated negatively impacting bee’s immune system.

- Whenever possible plant a pollinator garden. They will provide a source of nectar and pollen, nesting sites, and habitat for pollinators, butterflies, and other wildlife. They will provide you with a constant source of joy, amazement, and awe related to the beauty, complexity, and diversity of nature.