Carnivore Recovery: Wolves Return to Western Washington

We have doomed the wolf not for what it is, but for what we deliberately and mistakenly perceive it to be –the mythologized epitome of a savage ruthless killer – which is, in reality, no more than a reflected image of ourselves.”

For as long as man and canine have co-existed, the Grey Wolf (Canis Lupis) has inhabited a space of inherent contradiction; equally beloved and hated, scapegoated and immortalized. The subject of countless myths, legends and scientific studies, wolves remain one of the most fascinating and misunderstood members of the Animal Kingdom. In the modern era, they continue to spark controversy between those who view their presence with suspicion and scorn, and others who see their return to historic territories as a positive symbol for wilderness, conservation and biodiversity in the United States.

Controversy aside, wolves have been steadily increasing their range in the lower 48 states since their recovery began in the mid-1990s. Now, they have made a significant expansion in the North Cascades. Earlier this year, state and federal wildlife biologists confirmed a mating pair on the west side of the Cascades, the first in nearly a century!

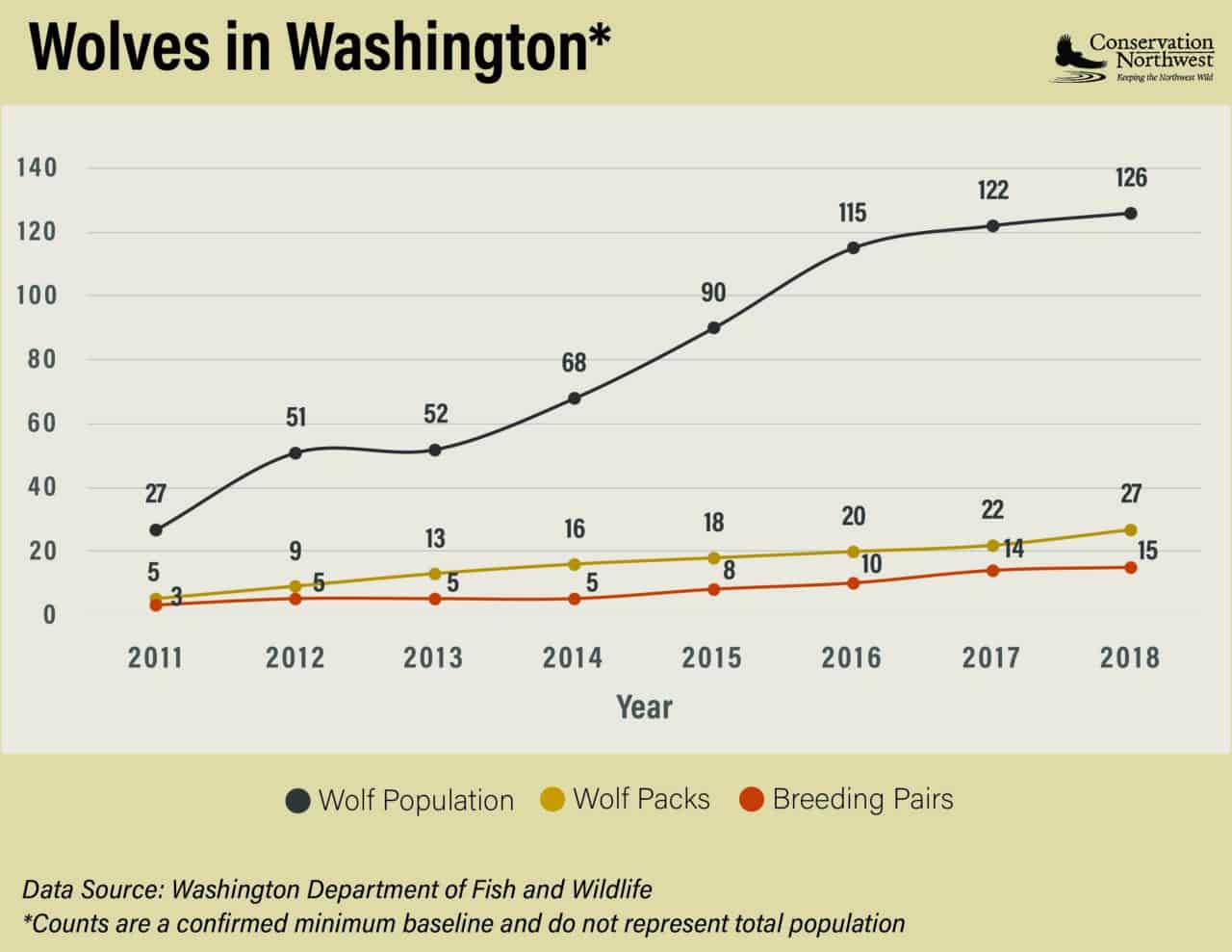

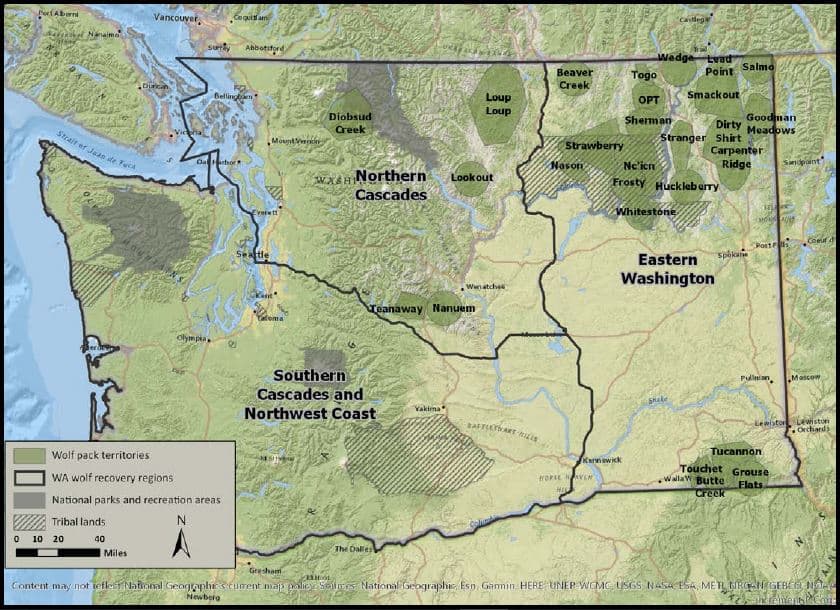

Wolves historically existed on both sides of the Pacific Crest but were eradicated from Washington entirely by the 1930s through hunting, trapping, and poisoning. They remained officially absent from the state until the Lookout Pack was confirmed by wildlife biologists in 2008 near the Methow Valley. Since then, wolf numbers have increased steadily every year, with 27 packs and 126 individuals confirmed in 2018. Nearly all of these wolves have been concentrated east of the Cascades, until now.

It is believed that a lone male wolf, pictured above, has been exploring the area north of State Route 20 near North Cascades National Park‘s western boarder since at least 2017, when he was captured and collared by wildlife officials in Skagit County. The Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife announced in early April this individual has recently been joined by a female companion, constituting a viable breeding pair. Biologists are calling this pair the Di0bsud Creek Pack after the creek that runs into the Skagit River near Marblemount.

How wolves migrated to Western Washington and why they are here remains somewhat of a mystery. Ben Meletzke, a wolf specialist for state Fish and Wildlife, speculates that populations on the east side of the state are running out of territory, and are thus moving west. “The eastern part of the state is definitely getting to the point of saturation for the number of packs we expect to see,” he stated in an article for Seattle Times.

Other theories suggest wolves may be moving south from Canada rather than traversing the Crest. Whatever the reason, the fact that they are here and seem to be thriving suggests that we have a healthy ecosystem with a wide variety of potential food sources to support a wolf pack. “Wolves are definitely a keystone species out there,” said Meletzke. “They need a healthy prey population to expand.”

The Skagit Valley hosts large populations of deer, elk, salmon and beavers, which could all be potential food sources for the Diobsud Creek Pack.

Now that these westside wolves have been established, wildlife managers will be closely watching how they interact with the local ecosystem and human communities. Wolves across the Interior West primarily feed on big game like elk and deer, often impacting ungulate population and distributions. Many wildlife scientists regard this as a good thing. As David Moskowitz, author of Wolves in the Land of Salmon explains;

“Large ungulates can significantly deteriorate many aspects of a landscape in large numbers over time without predators. A recovered population of wolves, paired with the presence of other large carnivores, can shift how prey species use the landscape, change population sizes of prey species and change the foraging behavior of prey species. These changes in turn affect how herbivores impact plant communities, potentially allowing trees and shrubs in sensitive habitats to rebound, which can lead to increased habitat value for a wide variety of other species such as birds and beavers. Changes in these species of wildlife in turn cause more ecological ripples across an ecosystem.”

This trophic cascade effect that Moskowitz describes has been well documented in Yellowstone National Park and other ecosystems with large ungulate populations. However, the coastal wolf populations of British Columbia and Southeast Alaska have shown a preference for salmon and smaller game, which are more abundant in coastal lowland forests, like the ones that dominate Washington’s west side.

Along with ecological effects, many are wondering how these new animals may interact with local livestock. Unfortunately, the increase in wolves throughout Washington has come at a cost for a number of ranchers in the state and the potential for future livestock predation is no doubt on the mind of many in Skagit County’s vibrant agricultural community.

An expanding wolf presence in the Skagit Valley will require an increased effort for state officials and environmental groups to mitigate conflict and ease public concerns. But as Conservation Northwest Executive Director Mitch Friedman points out:

“Washington continues to have a science-based Wolf Conservation & Management Plan and a constructive and a Wolf Advisory Group that’s finding common-ground and responsible paths forward for both wolves and people through dialogue between wolf advocates, hunters, ranchers, farmers, recreationists and other wildlife stakeholders.”

Indeed, David Moskowitz takes a similar view:

Washington’s Wolf Management Plan is probably the most progressive and scientifically and socially well-thought-out management plan of any Western state currently. If the state follows the guidelines for managing wolves in the state set out in this plan, wolf populations will almost certainly recover across much of the state, there will still be a huge livestock industry in the state and people will still have ample deer and elk hunting opportunities.”

It will likely be many years before we have any definitive data on the effects these new predators will have. It has barely been a decade since the first wolves appeared in the state, and researchers are only beginning to collect and analyze data for effects wolves are having in Eastern Washington. The future of wolves in Western Washington will depend on how quickly they expand and how local communities adapt to their new neighbors. In the meantime, the emergence of a wolf pack in the Skagit appears to be the beginning of another successful chapter in the Western Washington conservation story. Along with Fisher reintroduction last December, we are another step closer to realizing the goal of an intact ecosystem here in our increasingly wild and diverse backyard!

To learn more about wolves and the other incredible creatures we share this ecosystem with, be sure to check out our Naturalist Notes series.

You can help North Cascades Institute continue to educate our community on wildlife and conservation issues by making a donation during our Give BIG campaign. Learn more at ncascades.org/givebig. Thank you!