Evidence in the Indistinguishable: Wayfinding Techniques of Earth’s Organisms

This Naturalist Note is written by graduate student Zoe Wadkins, as part of the Fall Natural History Project In North Cascades Institute’s M.Ed. Residency coursework. You can view other students’ work here.

When two companions and I set sail from Berkeley, California to cross into what is considered French Polynesia, I had little idea of what the open ocean truly entailed. Regardless of the weather we faced, we were surrounded in an endless blue, temporarily marred by wind on the ocean’s surface. For twenty-eight days, we were without sight of land.

Presented with the opportunity through North Cascades Institute to research a natural history project of personal significance, I found myself returning to this moment in recent memory. When a fraction of difference in compass bearing can lead to success or undoing, what had guided us across an unknown landscape, and with such great accomplishment? Though our crew utilized nautical charts, compasses and sextants, we were quick to rely upon the convenience of global positioning systems to guide our travel. Yet for centuries, with little more than the indistinguishable appearance of the landscape, our navigational predecessors have found their way to fruitful ground.

Translated into a researchable natural history project, I found myself inquiring into natural indicators assisting travel. To do so, I sought to discover the wayfinding techniques employed by human, avian, aquatic, and mammalian species of Earth. Though by no means comprehensive, the following serve as testament to the incredible behavior of Earth’s beings.

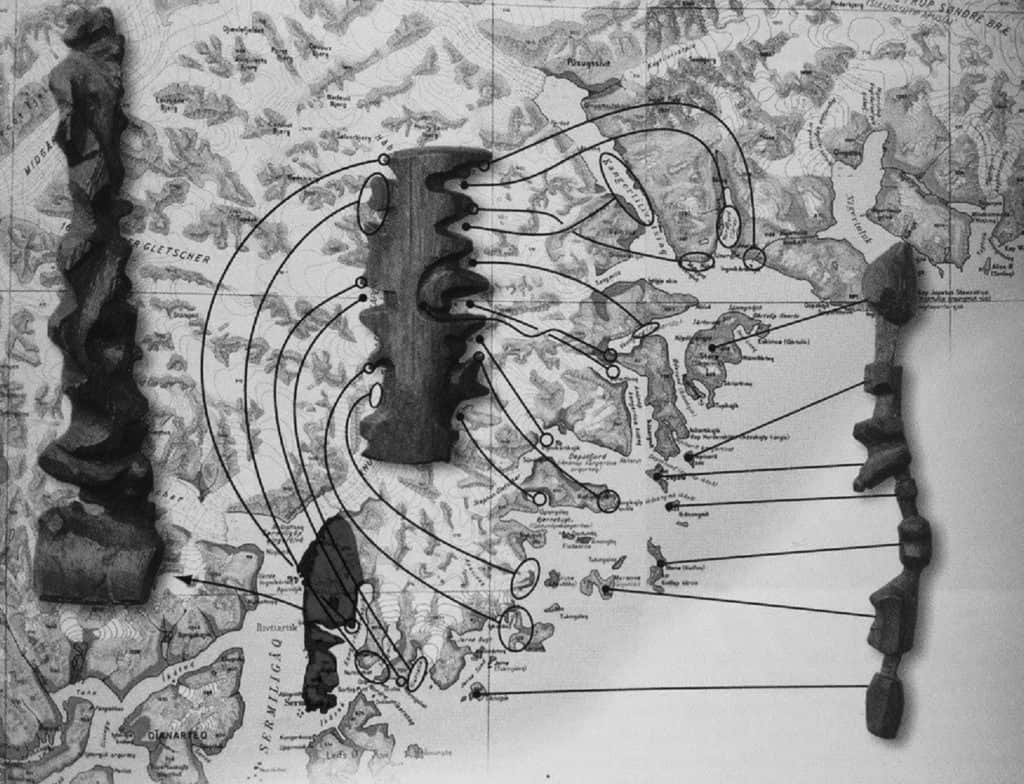

During early European contact with the Arctic, Eskimos conceded requests to generate maps of local environments. Fabricated from memory through mediums of pencil, wood, or stone, these maps minutely detailed scale and direction of the landscape, often involving distances of 150,000 square miles. When compared to studies that one in ten Americans cannot presently identify the United States on a map, Eskimo spatial memory becomes all the more profound. The richness of charted detail conveys a story of intimacy with nature built in part by time and through recurring travel over seemingly homogenous fields of ice.

Assisting deeper connectedness, livelihood in the Arctic embraces subtleties. Recognizing shading differences reflected off clouds and surrounding sky, well trained eyes can determine whether approaching landscapes will be open water or ice. Patterns of gathered sastrugi (snow ridges made by prevailing winds) serve as directional bearings amidst new territory. Likewise, landscapes are memorized looking backward off sleds, imitating the appearance of a return trip). As humans incorporate a variety of techniques in their travel, so too do natural communities living amongst them.

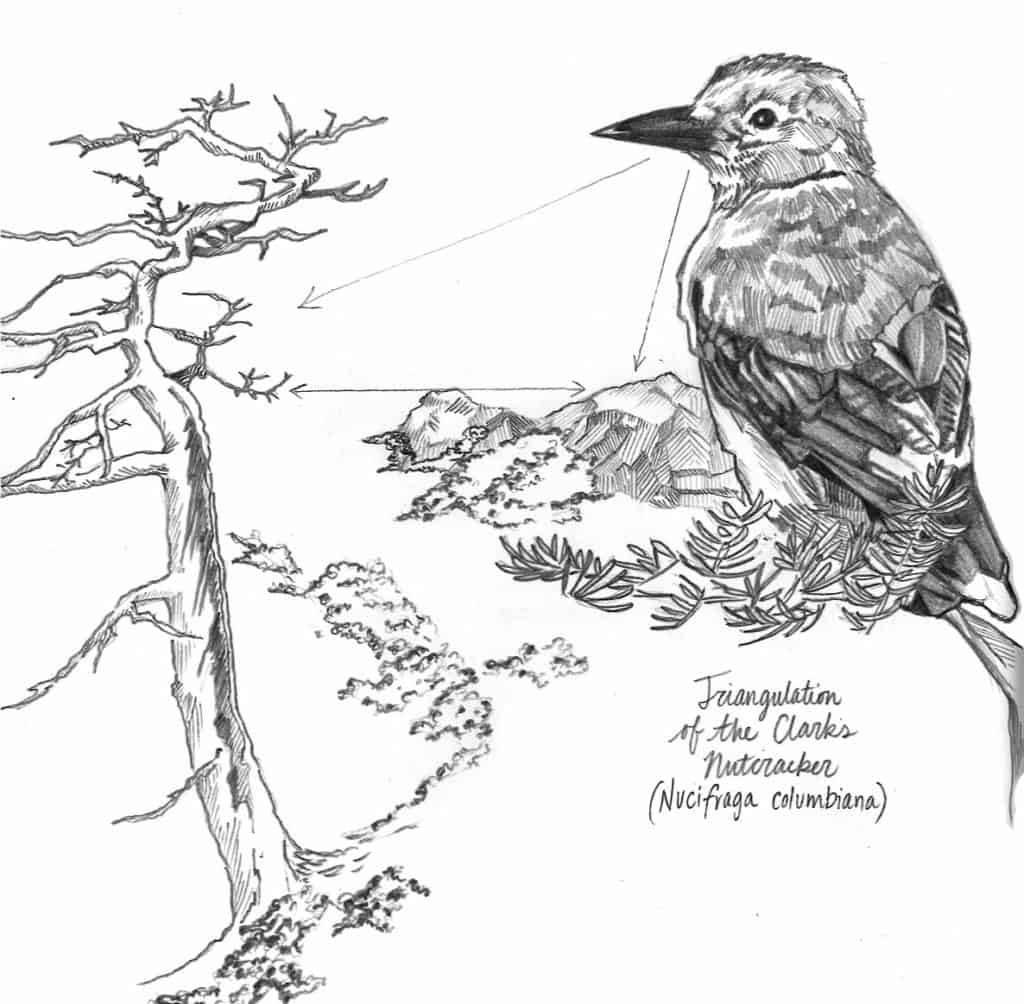

For avian species, combination of internal mapping and compass structures aid navigation, and utilize solar azimuths, geomagnetism and cognitive mapping techniques. For the Clark’s nutcracker (Nucifraga columbiana), triangulation predominates. Per year, an individual bird may gather more than 33,880 seeds in 7,700 separate caches. Though its territory may span hundreds of square miles, “…seven times out of ten, a Clark’s nutcracker nails it.” How does a solitary bird locate infinitesimal material with such outstanding success? Hypotheses point to spatial mapping devices that recall distinct memories of each site and the episodic details of what, where, and when they were placed. Constructing a bearing between two or three fixed landmarks, Clark’s nutcrackers design geometric relationships with their seed caches, spatially recalling distance, direction, and arrival from a multitude of angles. Remarkable, considering how often we fail to locate a single set of misplaced keys.

Whereas humans once embraced deep communion with Earth to navigate, the art of reading the land is now largely reserved to the animal. One or two generations ago, naming entire night skies were commonplace; now, it is rare to know a solitary star. Ironically, separate studies of homing pigeons and British cab drivers have shown that restricted navigational exploration (or reliance on GPS) causes a 10% decrease of grey matter in the hippocampus: the location of our brain oriented to space. While modern technology is revered as advancing human progress, have we truly achieved intellect in our industrial reliance? What do we compromise for convenience? Reflecting on the depth of knowledge required to know the land, what are we creating in separating ourselves from what surrounds us? And what sense of responsibility to the land persists?

For additional information about Arctic cartography, traditional wayfinding techniques, or Clark’s nutcracker triangulation methods, please see the following resources:

Robert A. Rundstrom, A Cultural Interpretation of Inuit Map Accuracy

Alan C. Kamil and Ken Cheng, Way-finding and Landmarks: The Multiple-Bearings Hypothesis

Diana F. Tomback, How Nutcrackers Find Their Feed Stores

Intimate interpretation is key in the awareness of all that surrounds life. Fabulous post!