Life After Glaciation: Upper Skagit River Bull Trout

Driving east on Highway 20, in route to my first day of class at the North Cascades Institute, I remember being struck by the wide valley narrowing into a winding gorge just outside of Newhalem, Washington. The Skagit River tumbled over chunks of deposited rock, glaciated jagged peaks pierced the sky and the turquoise waters of Diablo Lake provided tranquility.

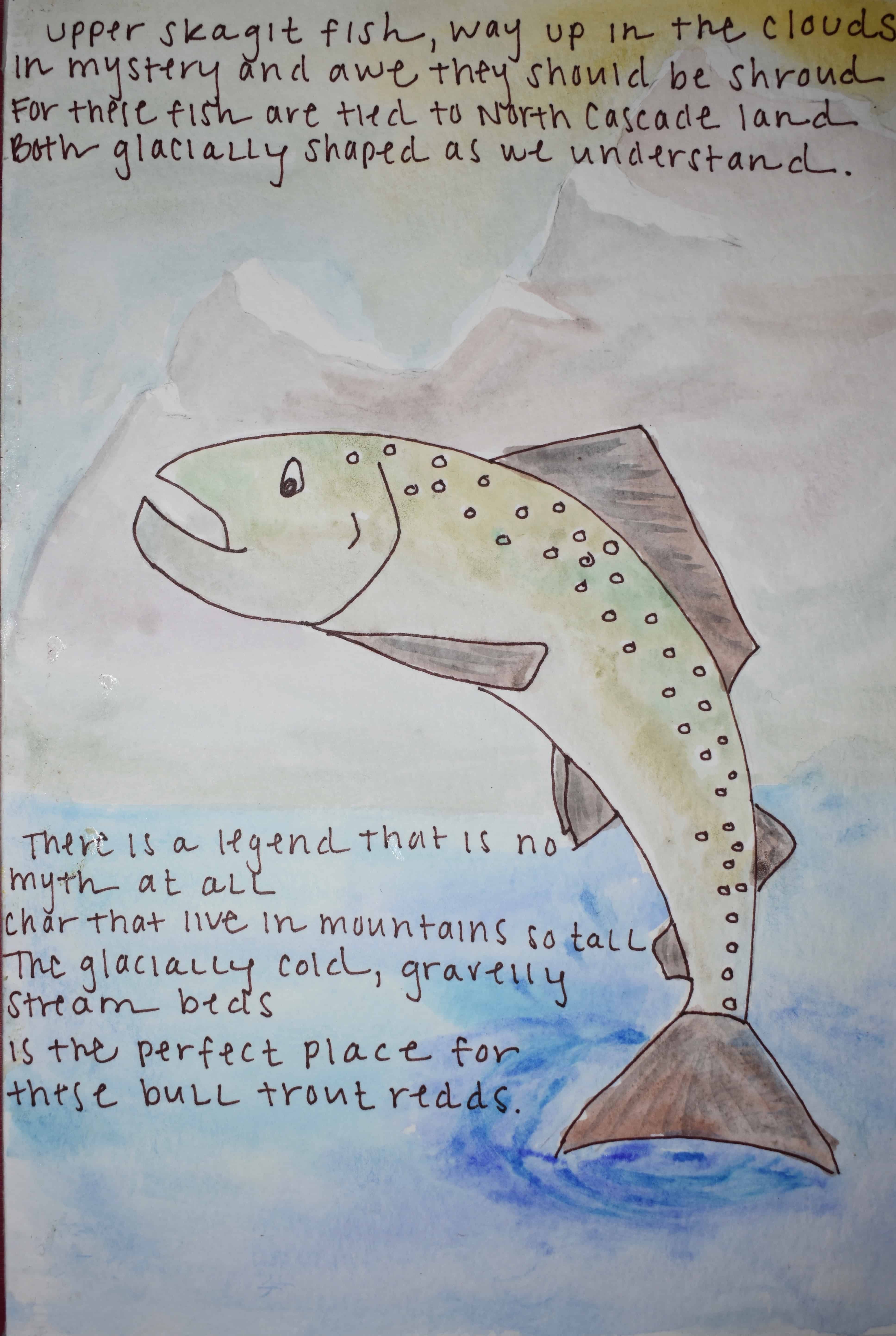

The next few weeks I became oriented to my new home and the biodiversity of the North Cascades. One such story that routinely popped up was a vague sort of story about how fish, specifically the threatened Bull Trout (Salvelinus confluentus), came to colonize the Upper Skagit River in the wake of glaciation. I wanted to delve further into the subject not knowing that the story of the bull trout, actually a char, reflects both enormous changes in landscape and an incredible story of colonization over the course of thousands of years. And…I wrote a poem about it…

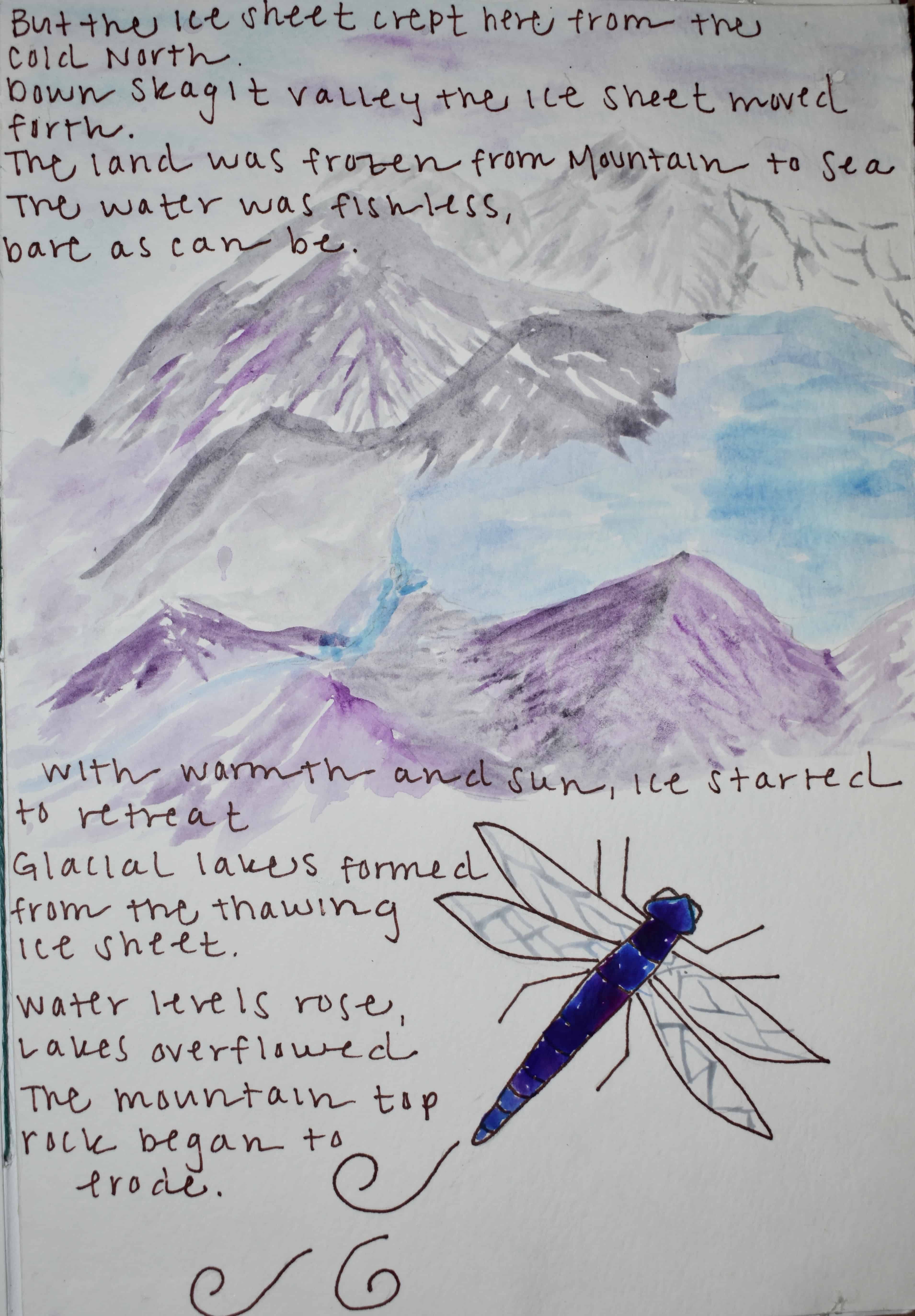

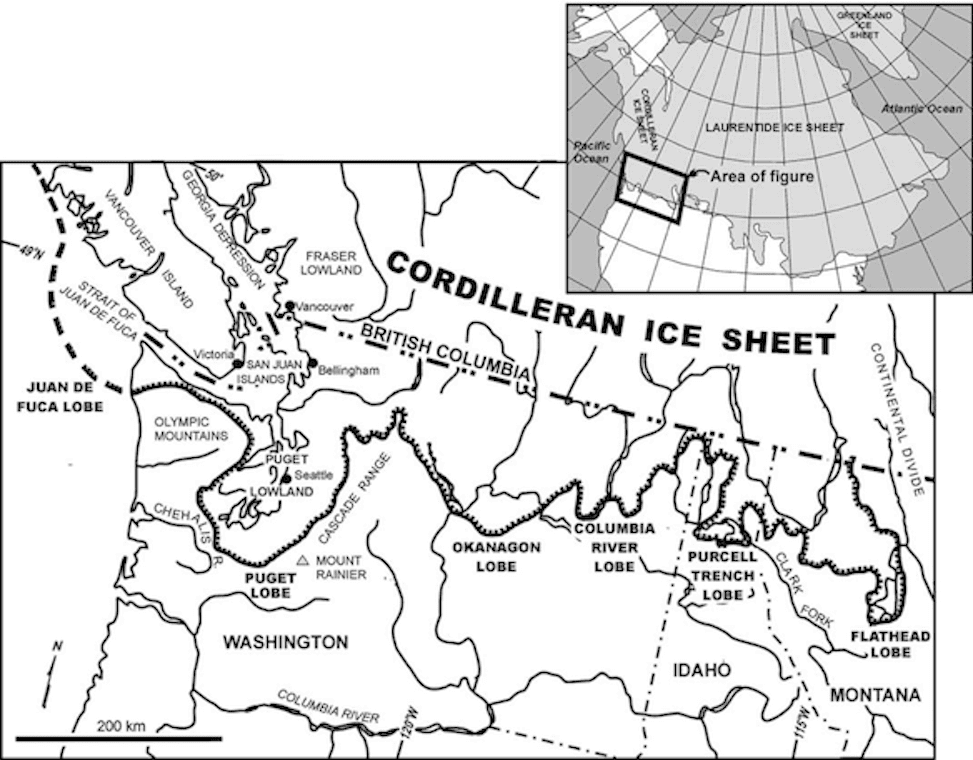

The story starts with the last ice age. Around 16,000 years ago, a mile of ice covered most of Skagit Valley. A mile of ice that would have left the landscape fishless. A mile of ice that would have crept down from British Columbia and swallowed all but the highest peaks. A mile of ice that would cover Northwestern Washington all the way down to Olympia before receding. A mile of ice changing large-scale landscapes through meltwater erosion.

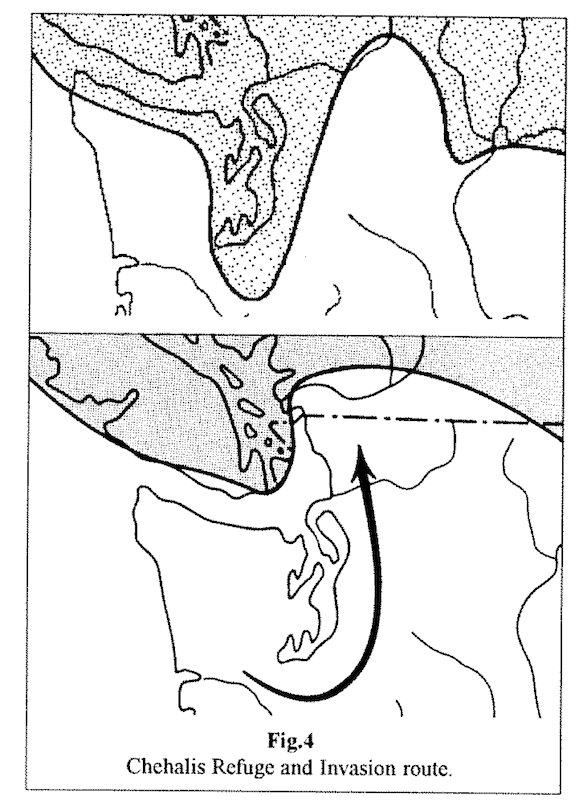

Bull trout, and other species of fish, found refuge below the southernmost extent of the ice sheet. These refuges included the Columbia Basin and the Chehalis River near Olympia, Washington. Bull trout in the Skagit River are most likely descendants from char that found refuge in Chehalis.

As the ice sheet began to recede, lakes and channels formed by the glacial melt. The bull trout were able to follow the meltwater from the southern refuge in Chehalis northward. Lower Skagit fish would have been able to enter through the connection with the Salish Sea as the valley became unglaciated. However, there is some evidence, supported by genetic analysis, that the Skagit Gorge at Newhalem would have been, even before dam construction, a natural fish barrier due to the steepness and water velocity. This means that it would have been implausible that Bull Trout navigated up the Skagit Gorge. Upper Skagit Bull Trout would have needed to find another way to colonize the Upper Skagit River.

One theory, supported by geological and genetic evidence, is that Bull Trout entered the Upper Skagit River through the Fraser River. This means that Upper Skagit Bull Trout would have followed the receding ice sheet all the way up to British Columbia and entered the Fraser River as the newly unglaciated habitat became available.

However, the habitat was only available for a short period of time before another, relatively small, advance of a glacier covered the lower Fraser River and pushed fish upstream. Upstream water, not being able to flow to the sea, began to inundate the surrounding landscape and form lakes and channels. One such channel linked the Fraser River to the Upper Skagit River through modern-day Silverhope and Klesilkwa creeks in British Columbia. The temporary connection, around 13,000 years ago, would have allowed bull trout to be funneled into the Skagit River where they are still found today.

This post was researched and written by Nicola Follis for the Northwest Natural History course as part of the Institute’s Graduate M.Ed. program. North

Cascades Institute has not extensively fact-checked the information contained herein and recommends researching other sources of information to enhance one’s understanding of the topic.

References:

1 Riedel, J. (2017). Deglaciation of the North Cascade Range, Washington and British Columbia, from the Last Glacial Maximum

to the Holocene. Cuadernos De Investigación Geográfica, 43(2), 449-466

2 McPhail, J.D., & Carveth, R. (1993). A foundation for conservation: the nature and origin of the freshwater fish fauna of British

Columbia. Queen’s Printer for British Columbia, Victoria, B.C.

3 Riedal, J.L. (2007). Late Pleistocene glacial and environmental history of the Skagit Valley, Washington and British Colombia.

PhD Thesis, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, British Colombia, Canada.

4 Booth, D.B, Troost, K.C, Clague, J.J. & Waitt, R.B. (2003). The Cordilleran Ice Sheet. Developments in Quaternary

Science, 1(C), 17-43.

5 Taylor, E., Pollard, S., & Louie, D. (1999). Mitochondrial DNA variation in bull trout (Salvelinus confluentus) from

northwestern North America: Implications for zoogeography and conservation. Molecular Ecology, 8(7), 1155-1170.

6 Riedal, J. L. (2018, October 30). Personal communication [telephone interview].

7 Smith, M.J. and K. Naish. (2010). Population Structure and Genetic Assignment of Bull Trout (Salvelinus confluentus) in the

Skagit River Basin. Draft Report to Seattle City Light, Seattle, Washington, Seattle City Light.

8 Connor, E. (2018, October 25). Personal communication [e-mail].

*Original art by Nicola Follis

This is really awesome!