The Triumph of Seeds: An Excerpt

Editor’s Note: The following is an excerpt from The Triumph of Seeds by Thor Hanson. It comes from Chapter Eight: By Tooth, Beak, and Gnaw.

By Thor Hanson

“Oh rats, rejoice!

The world is grown to one vast drysaltery!

So munch on, crunch on, take your nuncheon,

Breakfast, supper, dinner, luncheon!”

Robert Browning

The Pied Piper of Hamelin (1842)

Appendix F of the International Building Code stipulates requirements for keeping rats and other rodents out of all habitable dwellings. These include two-inch (five-centimeter) slab foundations, steel kick-plates, and tempered wire or sheet-metal grating over any ground- level opening. Conditions for grain storage or industrial facilities can be even stricter, involving thicker concrete, more metal, and curtain walls buried two feet below grade. In spite of all this, rats and their relations still consume or contaminate between 5 and 25 percent of the world’s grain harvest, and regularly gnaw their way into important structures of all kinds. In 2013, a trespassing rodent shorted out the switchboard at Japan’s ill-fated Fukushima nuclear plant, sending temperatures in three cooling tanks soaring and nearly setting off a repeat of the 2011 meltdown. The story made headlines around the world, with journalists, bloggers, and TV commentators all wondering what makes rats so interested in electrical wires. But the real question isn’t about what rodents like to eat; it’s about how difficult it is to stop them. Why on earth should a rat be able to chew through concrete walls in the first place?

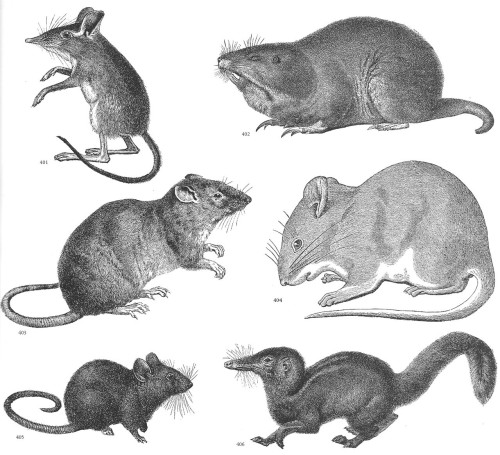

The name “rodent” comes from the Latin verb rodere, “to gnaw,” a reference both to the way rodents chew and to the massive incisors that help them do it so well. These teeth evolved in small mouse- or squirrel-like creatures approximately 60 million years ago. That’s approximately 60 million years before the invention of concrete, Plexiglas, sheet metal, or any of the other manmade materials that rats and mice now chew through. Experts still argue about the exact origin of rodents, but there is little doubt about what those big teeth were good for. While the family tree now includes oddballs like beavers, who chew wood, and naked mole rats, who use their teeth for digging, the vast majority of rodents still make much of their living the old-fashioned way: by gnawing seeds.

Before rodents came along, the ancestors of trees like oaks, chestnuts, and walnuts got by with little winged pips that offered scant protection from chewing. Fossils of these seeds look like lumpy flecks of chaff, insubstantial wisps designed to flutter a bit as they fell. Once the gnawing began, however, these plants and their rodent predators entered a virtual arms race: stronger teeth led to harder seed coats and vice versa, changing those ancient seeds into the acorns and thick-shelled nuts we’re familiar with today. (Other seeds responded by getting even smaller, in the hopes of being swallowed whole, or ignored altogether.) For the trees, rodents posed an evolutionary dilemma: the chance to get their seeds dispersed balanced against the risk of losing them entirely. For rodents, unlocking the nutrition in seeds turned out to be an evolutionary gold mine: they quickly became the most numerous and diverse group of mammals on the planet.

The notion of coevolution implies that change in one organism can lead to change in another— if antelope start running faster, then cheetahs must run faster still to catch them. Traditional definitions describe the process as a tango between familiar partners, where each step is met by an equal and elegant counter-step. In reality, the dance floor of evolution is usually a lot more crowded. Relationships like those between rodents and seeds develop in the midst of something more like a square dance, with couples constantly switching partners in a whir of spins, promenades, and do-si-dos. The end result may appear like quid pro quo, but chances are a lot of other dancers influenced the outcome—leading, following, and stepping on toes along the way. No one knows the exact sequence of events that gave us strong-jawed rodents and thick-shelled seeds; the story played out long ago and left only general clues in the fossil record. But few experts believe their sudden and simultaneous rise was mere coincidence.

In many cases, the relationships that developed became mutually beneficial—the gnawers got something to eat and dispersed a few of the plant’s seeds in the process. Hunger alone drives the rodent side of this equation, but for plants it’s like walking a tightrope. Their seeds must be attractive enough to be desired, but tough enough so that they can’t be devoured on the spot.

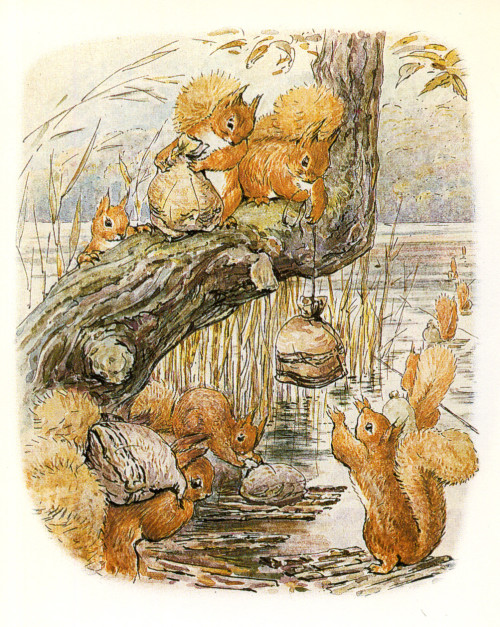

A hard shell forces rodents to carry seeds away and gnaw them open later, in the safety of a burrow. Ideally, the rodents then forget where they’ve hidden things, or perish before they get around to eating them. Take the example of Beatrix Potter’s book, The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin. Scholars think she wrote it as a commentary on Britain’s class system, but it’s also a story about seeds: if the squirrels on Owl Island gather and stash away nuts, and if Old Brown the owl attacks the occasional squirrel, then some of those nuts will go uneaten and the next generation of oaks and hazels will live on. (Nutkin managed to escape with only the loss of his tail, but we must assume that Old Brown is more successful on other attempts.)

Squirrel Nutkin of Beatrix Potter fame

Squirrel Nutkin of Beatrix Potter fame

Potter set her story in England’s Lake District, but if she had lived in Central America she would have put it right where I did my doctoral research, under the spreading boughs of a giant almendro tree. There, little Nutkin would have found not only plenty of squirrels to keep him company, but also other rodents: pocket mice, rice rats, climbing rats, and spiny rats, as well as pacas and agoutis, which look more or less like guinea pigs the size of small dogs. Like me, all of these species came to almendro trees in search of seeds. Unlike me, the rodents had been at it for thousands, if not millions, of years. (A dissertation only feels like it takes that long.)

With so many gnawing creatures hanging around, it’s no wonder almendro developed a shell hard enough to challenge a graduate student. But the nuances of seed defense rarely stop at physical protection alone. The ecology of this one rainforest tree makes it clear why so many seeds are stony, and why it takes a lot more than concrete to stop a hungry rat.