Why Natural History Matters

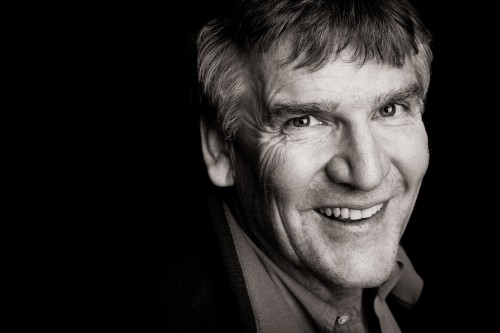

Thomas Fleischner, co-founder of North Cascades Institute, will read from The Way of Natural History at Village Books on July 8 at 4 pm. Info at www.ncascades.org/events.

By Thomas Fleischner

The world needs natural history now more than ever. Because natural history – which I have defined as “a practice of intentional focused attentiveness and receptivity to the more-than-human world, guided by honesty and accuracy” (Fleischner 2001, 2005) – makes us better, more complete human beings. This process of “careful, patient … sympathetic observation” (Norment 2008) – paying attention to the larger than human world – allows us to build better human societies, ones that are less destructive and dysfunctional. Natural history helps us see the world, and thus ourselves, more accurately. Moreover, it encourages and inspires better stewardship of the Earth.

Natural history encourages our conscious, respectful relationship with the rest of the world and affirms our sense of beauty and wonder. When we engage in this practice of attentiveness, we reaffirm our commitment to nurturing hope.

We are all wired to do natural history. Human consciousness developed in natural history’s forge – our patterns of attention were sharpened as we watched for danger and sought food (Shepard 1978). Practicing natural history is our natural inclination – a fundamental human capacity and birthright. Watch us as children: we turn over stones, we crouch to look at insects crawling past, we turn our heads to listen to new sounds. Indeed, as we grow older we have to learn to not pay attention to our world. The advertising industry and mass consumer culture collude to encourage this shrinking of the scope of our attention. But natural history attentiveness is inherent in us, and it can be reawakened readily.

It is easy to forget what an anomalous time we now live in. Natural history is the oldest continuous human tradition. Throughout human history and “prehistory,” attentiveness to nature was so completely entwined with daily life and survival that it was never considered as a practice separate from life itself.

In modern life, though, most people have become distanced from the kind of direct interaction with other patterns and processes of life, and other living beings, that was formerly taken for granted. Simply put, there has never been a moment in the story of human existence when natural history was practiced so little (Fleischner 2011).

What are the consequences of living in this bizarrely inattentive historical moment? Why is the need for the expansive attentiveness of natural history especially dire today?

The current gush of social dysfunctions – violence, depression, anxiety, alienation, lack of health in so many ways – coincides with the mass sacrifice of human interaction with nature, the greatest dearth of natural history in human history. We have come to see the world as a funhouse built of human mirrors, where we see only ourselves and narcissistic distortions of ourselves.

By contrast, natural history engenders humility and open-mindedness. It humanizes and grounds us by offering a larger perspective on the world. Natural history allows us – forces us – to see ourselves in proportion to the much larger fabric of the world, rather than as the beginning and end of the world’s story. Ultimately, natural history expands our sense of self into one of an ecological self (Naess 1987) and helps us to clarify our ecological identity (Thomashow 1996), by encouraging us to engage with nature – any place we can be in meaningful kinship with other species (Louv 2011).

Aldo Leopold (1993) famously noted that a sense of living “in a world of wounds” could accompany a growing ecological awareness. But this wounded world is also comprised of tremendously resilient beauty. Natural history is the process by which we learn to see this beauty – the process by which we fall in love with the world. My own observation over three decades of teaching natural history is that it typically has a centering, uplifting effect on people.

Among the attributes I have noticed in those who are attentive to nature are a greater sense of humility, affirmation, hope, joy, and gratitude. Natural history tends to lead to an expanded sense of a naturalist’s own humanity (Fleischner 2011). When shared, it promotes a sense of human connection. Laughter and warm hearts are often field marks of natural history in action.

Let us not beat around the bush here: natural history makes us better, psychologically healthier people, who are capable of being better citizens. A society comprised of naturalists – those who learn directly and broadly from more-than-human nature – is less myopic and less inclined to believe in the myth of human dominance. The practice of natural history connects us to the particulars of place, making the world less homogenous and abstract, and more interesting. The engagement, affection, and sense of compassion that flows from attention to these particularities of place and organism promote an ethic of stewardship. (And it must be said: natural history nurtures this tendency much more readily and naturally than does the austerity of ecological theory and abstract conceptualizations.).

Taking care of the world, whether we call it conservation, stewardship, or sustainability, depends on the accurate portraits of places, processes, and organisms provided by natural history. It is impossible to devise an effective conservation plan for an endangered species that we know nothing about (indeed, we would not even know that species was endangered without carefully natural history observations), or to prioritize habitats for protection if we do not know their extent or what relationships they harbor.

By focusing our attention on particulars – on actual plants and animals, on exact canyons and specific mountain slopes – natural history provides us models of adaptation, resilience and ultimately, of sustainability. Adaptation to life in, for example, the Sonoran Desert by a vascular plant gives humans a myriad of ideas as to how we, too, can conserve water and withstand summer heat. Moreover, we will have trouble designing livable, sustainable cities without paying attention to natural history specifics of place: When does the rain fall? How do native plants adapt to desert drought? What are the shifting seasonal patterns of shade and sunlight? Natural history quite literally grounds us.

Natural history also helps us to see the world accurately. Careful observation and description – the cornerstones of natural history – are the basis of all good science. Empirical observations provide the framework upon which integrative theories can be draped. Theories are only as valuable as the natural history observations on which they are based. As Charles Darwin once wrote in a letter to a friend, “accuracy is the soul of natural history.”

Accurate natural history undergirds all theoretical advances in understanding the world. Wallace and Darwin explored archipelagos, described the patterns of variation they observed, and the world was forever changed by the theory of evolution through natural selection. Entomologists crawling on hands and knees, tracking movements of ants, ponder theories of sociobiology. Geologists, sweating in dusty desert mountains, tracking fault lines and stratigraphies, contribute to a unified theory of plate tectonics. And geneticists, peering through microscopes, unravel the human genome. Every worthy science arises from a sturdy foundation in the careful observation and description of natural history.

Bottom line: natural history makes us healthier as individuals and, collectively, as societies. It provides the foundation for scientific inquiry, and for conservation. It honors the creation, and informs and promotes sustainability practices. And, not least, it is a whole lot of fun.

Reprinted with permission from the Journal of Natural History Education and Experience.

Acknowledgments

My gratitude to my colleagues and fellow participants in “The Natural History Initiative: From Decline to Rebirth,” especially to Laura Sewall and Saul Weisberg for helpful critique of these ideas.

References

Fleischner, T.L. 2001. Natural history and the spiral of offering. Wild Earth 11(3/4) [Fall/Winter]: 10-13.

Fleischner, T.L. 2005. Natural history and the deep roots of resource management. Natural Resources Journal 45: 1-13.

Fleischner, T.L. 2011. The mindfulness of natural history. Pages 3-15 in T.L. Fleischner, ed. The Way of Natural History. Trinity University Press.

Leopold, A. 1993. Round River. Oxford University Press.

Louv, R. 2011. The Nature Principle. Algonquin Books.

Naess, A. 1987. Self-realization: an ecological approach to being in the world. The Trumpeter 4(3): 35-42.

Norment, C. 2008. Return to Warden’s Grove: Science, Desire, and the Lives of Sparrows. University of Iowa Press.

Shepard, P. 1978. Thinking Animals: Animals and the Development of Human Intelligence. Viking Press. [reprinted 1998, University of Georgia Press]

Thomashow, M. 1996. Ecological Identity: Becoming a Reflective Environmentalist. MIT Press.

Copyright 2011, the author and the Natural History Network. Photo by Benj Drummond.